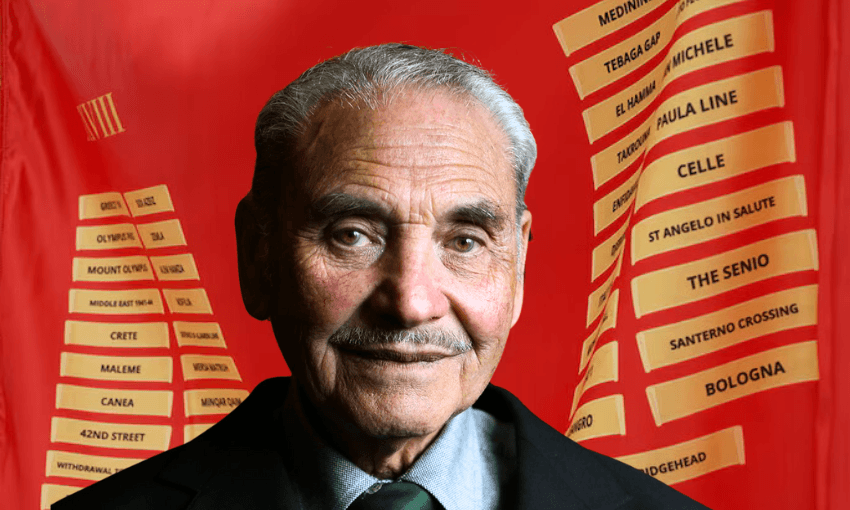

Sir Robert ‘Bom’ Nairn Gillies has passed away at 99 years old. He was the last surviving member of the 28th Māori Battalion, the most-decorated New Zealand battalion from World War II.

Bom Gillies (Te Arawa – Ngāti Whakaue, Ngāti Kahungunu) was known for his humility, strength, and his deep sense of loyalty to the men he fought alongside. Born in Hastings in 1925, he grew up in Ohinemutu Pā, Rotorua, within Te Arawa, a close-knit community that shaped his values and dedication to his people. His journey to enlist in the Māori Battalion was a determined one – Bom was just 17 when he first attempted to join, giving a false date of birth and trying three times before being finally accepted. For Bom, the pull of war was mixed with youthful curiosity and tales from older generations: “We’d never been out of town… Never even been to Mamaku,” he told Te Ao with Moana in 2022. “We wanted to see the world.”

A journey through hell and resilience

After training in Egypt, Gillies and his comrades arrived in Italy in 1943 during the fierce battles to capture Orsogna and later Monte Cassino. In freezing conditions and under relentless fire, Bom’s resilience was tested beyond comprehension. The attack on Monte Cassino, one of World War II’s bloodiest campaigns, saw the battalion face heavy losses and brutal conditions. Bom vividly recalled the horrors of machine-gun fire over the Rapido River and the minefields that lay in wait. A comrade, Captain Monty Wikiriwhi, was significantly injured, and others, like Joe Te Whare, were lost along the way. Through it all, despite receiving wounds and facing the traumas of war, Gillies continued to fight on.

Returning to Aotearoa in 1946, Gillies and his fellow B Company members (the battalion’s four rifle companies were organised along tribal lines) were welcomed with a large gathering in Rotorua. But he spoke often about the difficult reality facing Māori veterans: “I don’t think we were treated well at all. There remained places we couldn’t go to because we were Māori. Some RSAs wouldn’t accept us.” These challenges left an impact on him and fuelled his life-long advocacy for the battalion.

Gillies married Rae Ratima in 1948, who he met at a dance at his local marae. They had three children together, Martin (AKA Ture), Robert and Te Taupua.

A reluctant knight, an advocate for change

In 2022, Gillies was made a knight companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit, a title he initially declined, feeling he “wasn’t worthy” and believing the honour belonged to those who did not make it home. He eventually accepted the knighthood, viewing the recognition as a tribute to his fallen comrades. Gillies’ other honours included Italy’s Order of Merit, which he received on behalf of the battalion in 2019, again acknowledging not himself but “those who lie on foreign soil”.

Gillies’ commitment to his comrades didn’t end with the war. He tirelessly championed the campaign for the battalion’s battle honours to be displayed on its flag – an honour initially denied. He also worked to ensure that all Māori Battalion veterans received their rightful medals, even decades later. For Gillies, this was part of fulfilling a duty to his whānau and to history.

Reflections on war and legacy

Although Gillies was celebrated as a war hero, he became an outspoken critic of war, deeply reflective of its impact. “War is a waste of time. It solves nothing, but it makes some people rich… If I had my time over again, I would have been a conscientious objector,” Gillies told Te Ao with Moana.

Bom is survived by his children and six mokopuna, leaving behind a legacy of resilience, humility, and a fierce dedication to justice for his people. His passing marks the end of a monumental chapter in New Zealand’s history. With the death of Gillies, we lose the last living bridge to the 28th Māori Battalion’s heroic past.

This is Public Interest Journalism funded through NZ On Air.