Delivering the report 40 days ahead of schedule, the justice committee has recommended, by majority, that the bill not proceed.

The justice select committee has reported back on the Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi Bill, recommending it to not proceed following one of the most polarising consultation periods in recent political memory. The committee heard from 529 oral submitters over 79 hours and received more than 307,000 submissions. Approximately 8% supported the bill, while 90% opposed it, and 2% had no definitive view.

The report highlights the deep divisions both within parliament and among the public over the bill’s intent and implications. It also reflects frustration over the speed of the process and raises fresh questions about the government’s approach to Treaty issues.

The bill, introduced by Act as part of the coalition agreement with National and New Zealand First, seeks to define three principles of the Treaty of Waitangi in legislation: civil government, the rights of hapū and iwi Māori, and equality before the law. It would require these principles to be used when interpreting legislation – but not Treaty settlement Acts or the Treaty itself – and would come into force only if approved in a national referendum.

A majority oppose the bill

According to the committee’s departmental report, opponents of the bill raised concerns about its constitutional implications, its treatment of Māori rights, and the integrity of the process behind it. Submissions came from a wide range of individuals and organisations, including iwi, legal academics, NGOs, schools, and high-profile public figures.

In a report on the proposed legislation, the Waitangi Tribunal recommended the Treaty Principles Bill policy should be abandoned, while the New Zealand Law Society, the Human Rights Commission and a group of 50 King’s Counsel all submitted against the bill during select committee. Critics argued it misrepresents the meaning of te Tiriti o Waitangi, undermines tino rangatiratanga, and risks formalising a narrow view of equality that ignores equity and historic injustice.

Former prime minister Jenny Shipley described the bill as “a reckless project” that had “already caused unprecedented mistrust,” warning it could lead to “civil war” if progressed. Legal scholar Professor Andrew Geddis wrote that the Treaty was not just a contract but a foundational part of New Zealand’s nationhood.

Many submitters also objected to the idea of deciding indigenous rights through a referendum. Dame Anne Salmond called it “a dishonest process,” while Te Pāti Māori described the proposal as a “campaign of misinformation and division.”

The committee process was fraught. Opposition parties repeatedly sought more time for submissions and scrutiny, but those motions were often voted down by government members.

Green Party MP Tamatha Paul called the process “truncated” and “shabby,” while Labour’s Kieran McAnulty described it as “a woeful lack of leadership.” Te Pāti Māori criticised the rushed analysis of submissions and said parliament had no mandate to redefine Treaty principles.

The committee agreed to table or return submissions after the report, but under house rules, those submitted too late would not be part of the official record unless further authorisation is granted.

Collated submissions from organisations and campaigns were each counted as single submissions, regardless of how many names were attached. The largest submission was from Act New Zealand, supported by 31,022 others. The conservative lobby group Hobson’s Pledge submitted with 24,706 signatories.

At the other end of the scale, Tauranga Intermediate School submitted a student-led letter with 124 names. The Green Party submitted with 12,347 supporters.

Political divide remains strong

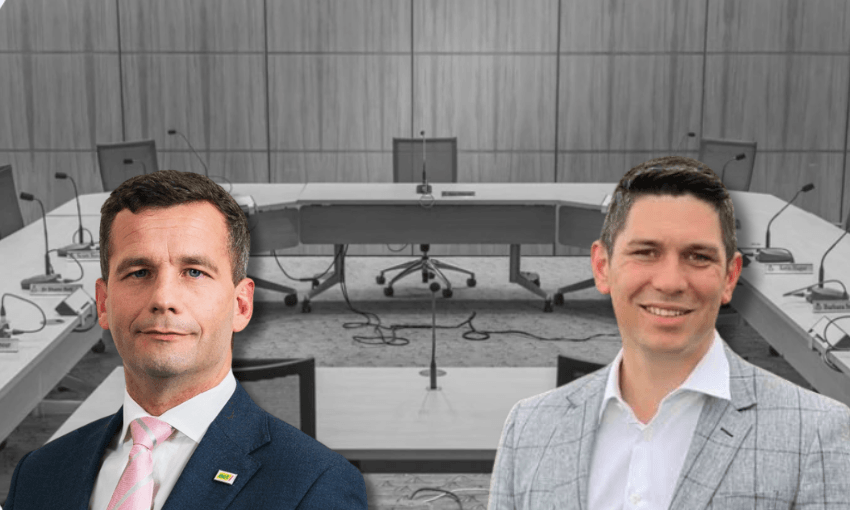

The select committee could not reach consensus on the bill’s future. The Act Party, which introduced the legislation, maintains the bill is necessary to “break parliament’s 49-year silence” on Treaty principles. “Dividing people based on ethnicity and giving them different sets of legal and political rights has never worked anywhere.” Act leader David Seymour has previously said.

Seymour’s position carries increasing weight – he is set to become deputy prime minister at the end of May, in a scheduled leadership rotation within the coalition. As Act’s flagship policy, the bill’s progress is now closely tied to Seymour’s growing influence within Cabinet.

Act argued that current interpretations – including separate health entities, reserved Māori seats, and consultation requirements under the Resource Management Act – are based on unelected interpretations and should be replaced by a legislated, democratically endorsed set of principles.

But the Green Party, Labour and Te Pāti Māori all strongly opposed the bill.

“The bill seeks to erase tino rangatiratanga, misrepresents the history of the Treaty, and undermines the courts,” said Paul. “It would damage our democracy and our international reputation.”

Te Pāti Māori said the bill should be withdrawn entirely. In its view, Māori never ceded sovereignty, and the proposed principles deliberately obscure the Crown’s enduring obligations under Te Tiriti.

Labour’s position echoed those concerns. “This is not about clarity,” said Labour justice spokesperson Ginny Andersen. “It’s about redefining the Treaty in ways that strip Māori of rights and dignity.”

With widespread opposition, the committee has recommended, by majority, that this bill not proceed any further. Despite the anticipated recommendation against the bill, the coalition agreement should see the bill up for a second reading in the house, where multiple promises have been made by the two other coalition leaders that the bill will be voted down.

Despite this, Seymour did not believe the exercise – estimated to have cost at least $6m – had been a waste of time or resources.

This is Public Interest Journalism supported by NZ On Air.

*this story previously incorrectly stated the Waitangi Tribunal submitted against the bill.