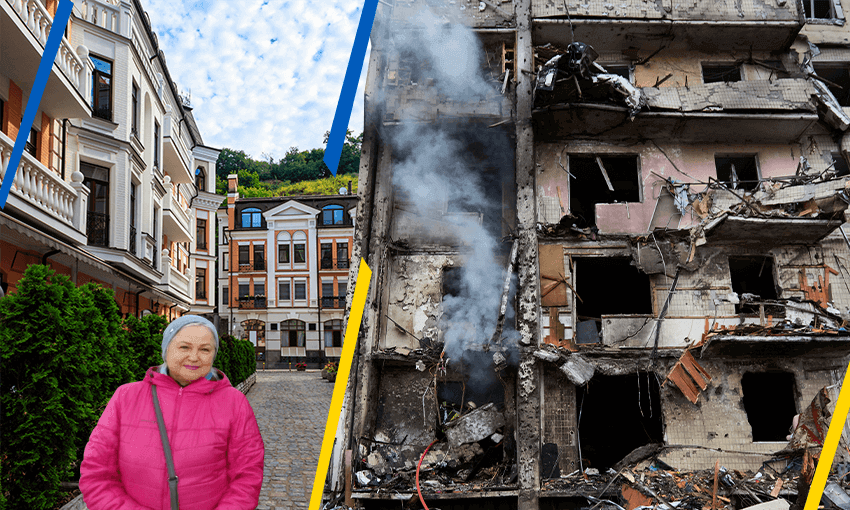

From her home near Tauranga, Giovana Tabarini followed remotely as her partner’s mother attempted to flee Ukraine – one of an estimated 10 million Ukrainians who have been displaced since Russia invaded just over a month ago. This is Valentina’s story.

On Friday, February 25, Valentina woke at 4:20am to the sound of two loud explosions. The Russians were on the outskirts of Kyiv, and Valentina, a 63-year-old Ukrainian, was hiding in her bathtub. Later, she would find out that a missile had shot a plane out of the sky, the fragments striking a nearby apartment block and setting it on fire.

The war had started the day before – air sirens and the thud of explosions shaking the outskirts of Kyiv as Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. As the first bombs started to fall, I was at my desk in Papamoa, watching in horror.

Valentina is the mother of my partner, Vika. To get Valentina to safety, we had booked her a flight from Kyiv to Alicante, Spain. It was due to depart in just a few hours – and now, the airspace was closed. The flight was impossible.

I sat at the kitchen couch in the Mainfreight office, where I work as a sales manager, and watched the freight being moved at the dock. I could not believe this was happening. Vika was already in Spain – she had flown there a week before to prepare for her mother’s arrival, which was now indefinitely postponed.

Valentina was in very real danger, on the outskirts of Kyiv, and our plan to get her out was in shreds. Covid hadn’t made things any easier. Valentina had wanted to get out earlier, but she was recovering from a bout of the virus and couldn’t fly until she tested negative and was feeling better. Meanwhile, Vika had caught Covid while travelling to Europe.

Dropping what I was doing, I headed home to give Vika a call. Her temperature was 38.5 degrees Celsius. She was struggling to grasp the situation, having initially thought all of our preparations to help Valentina were a bit of an overreaction. Now, it was real. War had begun, and she was scrambling to buy her mother a bus ticket to Krakow, Poland.

From this point, the timeline becomes blurry, because I’m seeing it all from New Zealand time – hours ahead of Ukraine and Europe.

On Thursday, Valentina spent seven hours at the bus station, trying and failing to get onto any one of the buses that showed up. None of the buses that Vika had managed to get tickets for arrived.

The biggest challenge was getting Valentina out of Kyiv: there was no fuel in the city, and a drive that would once have taken 20 minutes was now taking seven hours. Many people were getting stuck, running out of fuel. Everyone was in panic and fleeing for safety, with traffic at a complete standstill.

I called Erika, a friend whose family lives in Hungary. She got in touch with her brother, who would see what could be done. Her mother offered Valentina shelter, if she could get across the border.

That night, I felt like the most helpless person in the world. From New Zealand, there was nothing I could do to help Vika feel better about her Covid symptoms. I checked some care packages online, but nothing seemed quite right, or worth the money. I asked if there was anything I could do to help her, to help her mother. “No. Pray,” was her response.

Meanwhile, in Kyiv, it was the early hours of Friday, and Valentina had just been woken by the nearby explosions. We had more tickets for buses scheduled to depart that day, but the main bridge out of the city, Ipren, had just been bombed, cutting off access.

The Russians were now in Kyiv’s north, fighting the Ukrainian army. Valentina was at home hiding in the bathtub. Nothing made sense anymore. Rumours were spreading that the Russians had changed their gear to look like Ukrainians and were shooting civilians as they came to ask for help.

What a horrible feeling. I wondered about the Mainfreight team in Kyiv. What was the plan to keep them safe? I called Dan Plested, son of company founder Bruce, to check. It went to voicemail. The branch manager in Poland also didn’t pick up.

On Saturday morning, I woke up to a message from Dan. I told him about Valentina, explaining that she was alone: her husband had long since passed away, Vika was her only child. I told him about our failed attempts to get her out. “This is the only thing I can think of,” I wrote, “maybe putting her in a truck with the other team or anything we are doing to help the team there?”

Dan immediately contacted his network, coming back just an hour later with the contact number for Alexandrin Macevei, a Mainfreighter in Romania.

I called Alexandrin, the branch manager in Cluj-Napoca. He answered promptly, and I was immediately relieved: he spoke great English and communication was easy. He checked whether Valentina had papers. He said that, in wartime, bombing typically intensifies at night, when anything that moves is a target. Leaving in the dark was not an option. So, we had to sit tight.

In the meantime, Dan got in touch to tell me that the Mainfreight team in Ukraine were all staying put. The Ukrainian government had just started conscripting reservists, to bolster their national army. No men between 18 and 60 were permitted to leave the country. This order covered many of the Mainfreight team and, since the men were staying, the women decided to as well.

Alexandrin, meanwhile, had contacted Valentina. “Just spoke with her,” he messaged me. “Will try to evacuate in the morning. Keep you posted.”

Vika was in contact with Erika’s mother, trying to see what else could be done. Still suffering from the effects of Covid, Vika had finally started eating again and felt that her body was surprised to have food. She couldn’t smell or taste anything, but the food looked great. While we waited for news, I sent her photos of our dog, Preto, as well as other cute animal videos. I was starting to feel hopeful.

That evening, Vika messaged. “No luck with the escape, Gio. There was bombings happening on the route she was thinking of leaving and travelling. All other options at the moment are not possible. The biggest problem is no ability to top up petrol. Artur is in touch with her and looking for other options.”

Artur, a team member from Mainfreight Kyiv, had some experience with this kind of situation. He had fled Donetsk a few years earlier, after the Russians invaded Crimea and separatists kicked off a civil conflict in southern Ukraine. Some of his friends had just almost frozen on the road out of Ukraine as temperatures dropped. This was not a good way out.

That night in Kyiv, a 36-hour curfew was introduced. While she waited for her next chance to move, Valentina spent most of her time talking to people to figure out which shops were still stocking food and medicine, as well as researching possible escape routes.

I called Vika at 1.30am, my sleep broken by my uncomfortable bed (my house is under renovation, so I’ve moved into my van). She told me her mother was at Artur’s house and would be going to the train station shortly.

What she didn’t tell me was that Valentina had already taken advantage of a 15-minute window of no shooting that morning. She threw some clothes and medication into a backpack and a wheeled suitcase. A friend picked her up and dropped her at the nearby underground station, her whole life now packed in two small bags. Only one train line was functioning. The rest were being used as bomb shelters.

Valentina waited an hour for a train. After arrival at the closest station, she walked for an hour to reach Artur’s house. She could hear shooting the whole time.

Knowing none of this, I called Alexandrin. “We have a train in two hours that she will depart on,” he told me. It would take around 14 hours for the train to reach the border.

Meanwhile, Artur introduced Valentina to Valeria, a team member at Mainfreight Kyiv. She was also fleeing, with her mother, her grandma, her 14-year-old brother, and her dog. When they arrived to the station, many people were trying to get on the train. Artur and his friend pushed Valentina on, passing her bag up and over the heads of people.

The train was freezing. Valentina put on all the clothes she had with her, to keep the cold out. Most people were standing in the packed carriages, but she climbed to the upper bench and managed to sit and even lie for a bit. It was a long 14 hours. They didn’t know if the people at the other end were going to show up or not.

I couldn’t sleep until I heard that Valentina had managed to get to the train, and the train had departed. I was happy to hear they were on their way, but when I messaged Alexandrin, I learned that the train would not take them all the way to the border. For a reason I still don’t fully understand, it took them to a village some 100km short of Romania.

Alexandrin called 20 or so people that night, to try to arrange Valentina’s onward travel. After contacting many acquaintances, including a mayor of one of the border towns, he remembered a guy called Ivan, who had done some transport for them a few years ago. Ivan could recall Alexandrin, and decided to help. He organised two cars to pick up Valentina, as well as Valeria and her family, from the Batiovo train station. The cars would transport them to Solotvyno, on the Romanian border.

The station at Batiovo was small and thronged with people fleeing Ukraine. Valeria knew what to look for, though, and they easily found the cars that had come for them. An hour or so later, they reached the Romanian border. They were given food while their paperwork was processed. It took very little time. They were lucky – at other border crossings, people faced waits of 24, even 48 hours.

They had done it. We had done it! They were across the border.

Alexandrin was there to meet them as they entered Romania, taking them to the apartment he had organised in Cluj-Napoca.

Back in Papamoa, we were flooded with relief. The whole office dressed up in support of Ukraine. We took pictures – a burst of blue and yellow – sending them to our friends in Ukraine. Artur wrote back: “Very nice to see such great support from Mainfreight team and understand that we are not alone.”

Finally, our plan was back on track. Vika quickly organised for Valentina to fly to Madrid on March 4. At 8.20pm that day, mother and daughter were finally reunited. After a day, they headed to Alicante. From here, Phase 2 swung into action: finding a semi-permanent apartment for Valentina, and registering her with the Spanish authorities.

Through more contacts, we found friends to help source an application and translate a letter, to introduce Valentina to the authorities properly, in Spanish. The route to apply for asylum is opaque, though. Without a national ID number, it is very hard to live in Spain. Finally, after many apartment viewings, a landlord agreed to sign a rental agreement without that number.

His nationality? Russian.

This is not where the story of Vika and Valentina ends – there is plenty more work to do to make sure Valentina can stay in Spain. But for now, she is safe.

Want to help? Many charities are working within Ukraine and in neighbouring countries to address the humanitarian crisis, and are taking donations to support their work.

International Committee of the Red Cross