For four days Te Matatini transformed everyday life into an experience that was unapologetically Māori. The impact of that was life-changing, writes Charlotte Muru-Lanning.

It was beyond the gates of Eden Park, after the four-day national kapa haka competition had come to a close, that the effects of being immersed in the world of Te Matatini really took hold.

On the evening after the finals we were out for dinner on Karangahape Road. In an indecisive mood, and with a lengthy menu confronting me, I landed upon a blackberry-laced cocktail. One sip in, and my brain made the journey to the fruit-filled garden that wraps itself around the whare my great-grandparents built next to the pā. Among the echoed discord of plates and cutlery, my ears repeatedly deceived me: turning conversations spoken entirely in English at the table next to us into what sounded, to me at least, like humming kōrero. Within the ambient restaurant music, I felt my ears searching for kupu, for taonga pūoro, for a Māori guitar strum. While exiting the restaurant, up a flight of stairs, we heard haka. And then stood still in disbelief as it dawned on us that there was in fact no haka, just the muffled acoustics of the restaurant below.

As we looked for a spot to order a taxi at the end of the night, we were sure this time. A harmonious waiata was spilling out of the teensy karaoke bar across the road. Finding a gap in the traffic, we shuffled over for a closer listen, agreeing with confidence as we power walked: “that is definitely waiata”. And yet, as we neared and our ears gained clarity, the song slowly morphed into Rihanna’s ‘Don’t Stop the Music’ (which, as an aside, and after further listening, would actually make an excellent poi tune).

There’s probably plentiful scientific data exploring the cognitive effects of cultural and linguistic immersion. And yet, I don’t even need to search Google Scholar. I have my own qualitative data set right here.

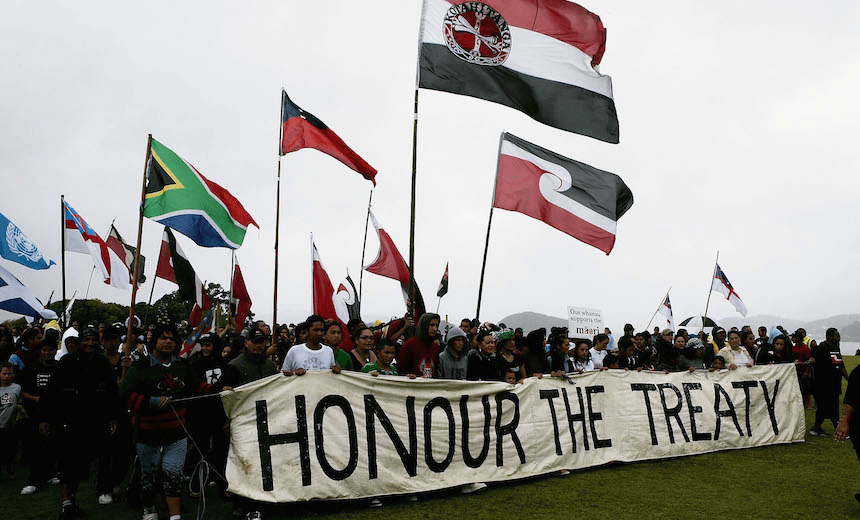

Te Matatini saw 40 of the best kapa haka groups in the world descend upon Tāmaki Makaurau. And without fail, each day was brimming with T-shirts proudly declaring iwi affiliations, tino rangatiratanga flags fluttering overhead, impressive pōtae, immense taonga, kaimoana galore, coffees ordered in te reo Māori, and kaihaka on stage with chins raised confidently. Almost everything was Māori, and proudly so.

For some Māori, this kind of everyday immersion is just plain ordinary. Whereas, for others, the inverse is true. In my case, no matter how proud I might feel, being Māori has almost always felt like something that’s expected to politely find space within the claustrophobic cracks of te ao Pākehā: a hushed karakia before dinner, begrudgingly performing kapa haka at high school assemblies to a room full of giggles, or, an apologetic “friendly” reminder to the flat group chat to “please wash the tea towels separately”.

That’s why having everyday life suspended for this celebration of all things Māori, in the suburb in which I’ve lived most of my life, was so profound. I get the impression that I’m not the only one who felt this way.

Te Matatini was streamed on TVNZ+ 1.8 million times, making it the most watched programme on the channel last week. Over 900,000 New Zealanders tuned into the livestreams or watched on television and 100,000 attended in person – numbers that only underscore the absurdity of the millions of dollars in funding disparity between the competition and the likes of NZSO and the Royal New Zealand Ballet.

Social media was alight with excited chatter about being able to readily access kai Māori – fry bread, foil-wrapped hāngī, pāua fritters, kina shots, mussel-laden chowder, raw fish, platters of half-shell oysters, steamed pudding – something that’s seldom available to buy in the central city. Melodies, rhythms and instruments rarely heard on our radio waves permeated the stadium and its surrounds. Te reo Māori speakers and learners buzzed over the opportunity to kōrero in the marketplace. The diverse concerns of iwi were quite literally given centre stage. Kaihaka were rightfully transformed into superstars as they stepped onstage. Everyone became kapa haka experts. Commentators fawned over the uniquely Māori fashion on display. And perhaps slightly more questionably, on TikTok, some lusted over the dapper men of Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei. Te ao Māori infiltrated even the most unexpected and curious corners of our culture for the week – and the crowds seemed to happily embrace it all.

This explicit Māori-ness didn’t exist on its own, rather, it was accompanied by inclusivity. The crowds were diverse, translations of performances were available in multiple languages and Lebanese, Cantonese, Tongan and Cook Island food stalls punctuated the kai options. As if in response to the humdrum angst surrounding terms like co-governance, Te Matatini showed exactly how fruitful shared arrangements can be.

By now, the stalls and stage will have been packed down. The 40 kapa haka groups will have all returned home along with their whānau, friends and tutors. After years of preparations, the physical presence of the competition might have been fleeting, but its impact resonates. Not just in our ears tricking us into hearing waiata as we left restaurants, but in the alternatives it opened up in our everyday lives. Of being able to access our own kai. Of being able to kōrero Māori while we order that food. Of actually hearing waiata Māori when we leave the restaurant at the end of the night. It gave us a glimpse into a Māori future.