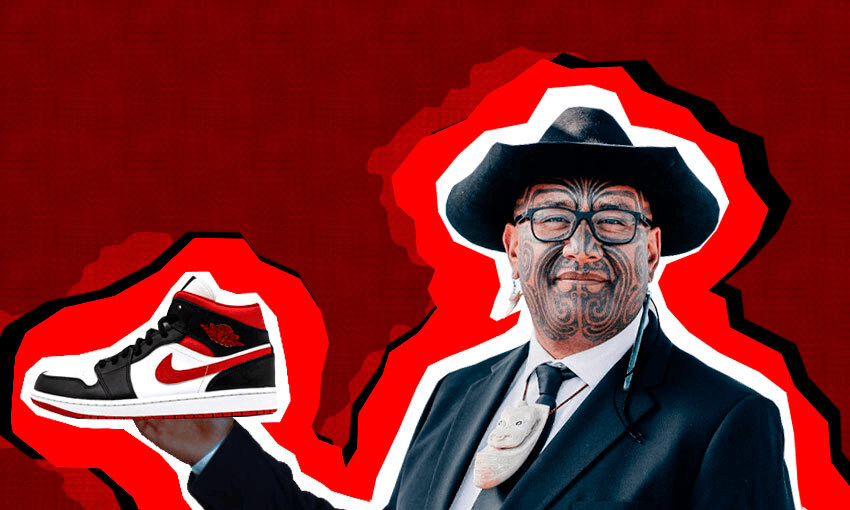

A pair of Jordan sneakers worn by Te Paati Māori co-leader Rawiri Waititi led to some contentious comments in parliament last month. But why would a pair of shoes that are relatively commonplace spark such a reaction – and what does it say about where we’re at politically?

When Te Paati Māori co-leader Rawiri Waititi delivered his maiden speech in the house in December 2020, he warned he would act like a pebble in the shoe of parliament – an unapologetically Māori voice in the halls of power.

Eleven months later, in a curious exchange during question time on October 21, it was Waititi’s shoe choice (Nike Air Jordan 1 mids in gym red) that became that pebble in the shoes of some of his parliamentary colleagues.

On that Thursday afternoon, a point of order was brought to the speaker by a grey-suited Act leader David Seymour, who sits next to Waititi in the house.

“I know you may not be used to being asked for sartorial advice,” Seymour said. “But are Air Jordans an example of business attire?”

The speaker Trevor Mallard responded: “I’d tend to say it would depend on the business you’re in.” He followed jovially with: “The business which Air Jordans are normally associated with in my interpretation is not quite the business we expect to take part on these precincts.” Mallard decided not to make any official ruling on whether sneakers were or were not acceptable attire in the house.

Waititi says subsequent conversations with Mallard outside the house and over the phone confirmed the type of business the speaker was alluding to; that of basketball players but also drug dealers and gang members. The day after the interaction he tweeted: “What you didn’t see yesterday was on my way out of the chamber, the Speaker said to me ‘Jordans are usually worn by drug dealers and gangsters!’”

The tweet led to numerous comments condemning Mallard, with many of those expressing concern about what they saw as the stereotyping and racism implied by his remarks.

Mallard responded to the controversy in tweets saying he “really liked” the sneakers in the 1980s “when they first came out”. But, he said he “couldn’t afford them” and that “only professional basketballers, rich people, drug dealers and gangs had them then”.

Mallard also expressed discomfort at the accusations of racism: “What makes me very uncomfortable with this is the racist assumption that appears to sit behind some of the comments.”

Waititi remains surprised by what he describes as an “unusual interaction”.

“I’ve worn my Jordans for a little while now in the house,” says Waititi. “But for some reason somebody took offence to me wearing them that day.”

He credits his passion for sneakers to the years he spent studying and living in Auckland. “Urban streetwear was part of my upbringing,” he says.

Beyond what they mean to him personally, he sees sneakers as a way to make parliamentary politics more reflective of those he represents. In other words, it’s about politicians quite literally walking in the shoes of their constituents.

“Not all of us represent the suit and tie regions or electorates,” he says. “We represent real people on the ground who don’t wear ties, who prefer to wear Air Jordans.”

Sneakers have long held a cultural meaning, signifying ideas around national identity, status, race, class, gender and criminality. While nearly everything we wear is in one way or another political, when it comes to sneakers, the complexities of associations sets them apart from other types of footwear.

The response to the Jordans from Seymour and Mallard didn’t just appear out of nowhere. The specific genre of sneakers Waititi was wearing carry with them a cultural weight influenced by their American origins. While streetwear sneakers are of course not worn by solely one group – in fact their aspirational image is desirable across the board – they’re intertwined with a complicated and politically charged mix of identities: inner-city, urban, African American, hip hop-influenced, counter-cultural and criminal.

University of Auckland ethnomusicologist Kirsten Zemke says because shoes like this are tied to the hip hop community, “we do get that association with race and racism”.

Despite their high price tag, Jordans in particular have been positioned in opposition to authority since they hit stores in 1985. In 1984, when Nike signed basketball player Michael Jordan to an endorsement deal, he wore his signature Air Jordans in NBA games, in defiance of league rules. Nike continually paid his $5,000-per-game fine, while airing ads declaring: “The NBA can’t keep you from wearing them.”

A degree of moral panic around certain types of sneakers took hold throughout the 80s and beyond as pristine white Air Force 1s became associated with drug dealers and colloquially known as “felon shoes”. In 1990, Nike’s Spike Lee-directed sneaker ads were blamed by media for a string of “sneaker killings”, and in Run-DMC’s 1986 track ‘My Adidas’, the hip hop pioneers defended their Adidas Superstars against their associations with crime,rapping: “I wore my sneakers, but I’m not a sneak.”

While many of these cultural associations originated in America, and are weaponised against black and brown communities there, the same negative assumptions have developed here too, says Zemke.

As hip hop culture has been adopted in New Zealand, particularly by Māori and Pacific Island communities as an extension of both individual and group identity, the same negative stereotypes have developed. We see it in the increasingly uncommon but still existing nightclubs that turn away those in pristine $300 sneakers (while at the same time happily welcoming others in haggard-looking gladiator sandals or uncomfortable dress shoes that hurt to dance in), and in this case we see it in our parliament.

It’s not Waititi’s first sartorial controversy. He’s previously faced scrutiny for wearing a hat and was ejected from parliament for wearing a hei tiki in place of a tie, which eventually led to a change in parliament’s dress code. Now it’s his shoes.

Despite his newness to parliament, Waitit’s aesthetic is well-established: his personal style is a distinct collage of influences from head to toe.

Waititi was brought up on a dairy farm on the East Coast. His recognisable cowboy hat, which he’s worn since he “was a young fulla”, is a nod to his rural roots as well as his tūpuna who fought in World War II. Their company within the Māori Battalion was known as Ngā Kaupoi (cowboys), because horses were a common mode of transport along the East Coast. He wears the hei tiki instead of a tie simply because, “Well that’s me,” he says. “I’ve always worn taonga.”

To Waititi, the “shoe debacle” is a reflection of an outdated parliament. “I think we’re holding on to some customs that really don’t reflect our society in Aotearoa.” To him, and many others, wearing a pristine pair of sneakers is no less respectful or dressy than a pair of leather brogues or shiny court shoes.

Parliament, he says, “should be reflecting the communities and the constituents that you represent”.

The taken-for-granted Pākehā corporate wear of parliament is in itself a statement about what power and authority should look like. Zemke says the discomfort Waititi’s sneakers provoked in a couple of members of parliament brings up important questions around respectability. “When we think about the formality of parliament, we know the dress codes are based on colonial ideas of what is formal,” she says. Rather than conform to these standards of appearance, these types of shoes, though being no less appropriate, disrupt that.

Visually displacing the sombre tailoring we’re so used to seeing in the Beehive, Waititi’s bold sneakers stand out in that environment because they dismantle “that very formal Eurocentric view of what respect is,” she adds. These days you’re likely to see kicks in spaces deemed respectable by western standards: corporate boardrooms, the red carpet or high-fashion runways. But at the same time, there’s nothing to say that shoes worn by black, brown, Māori or Pacific people in any other setting should denote anything less, or that the people wearing them deserve any less respect. “They’re not inherently disrespectful unless you find hip hop disrespectful,” says Zemke.

Converse, cowboy boots, Crocs and red bands are all regular shoe choices for Waititi. But “at this particular moment and in that space, I think Jordans are a lovely touch,” he says.

“I don’t think it’s the clothes that make the man,” says Waititi, “but sometimes it is hard to look this good.”