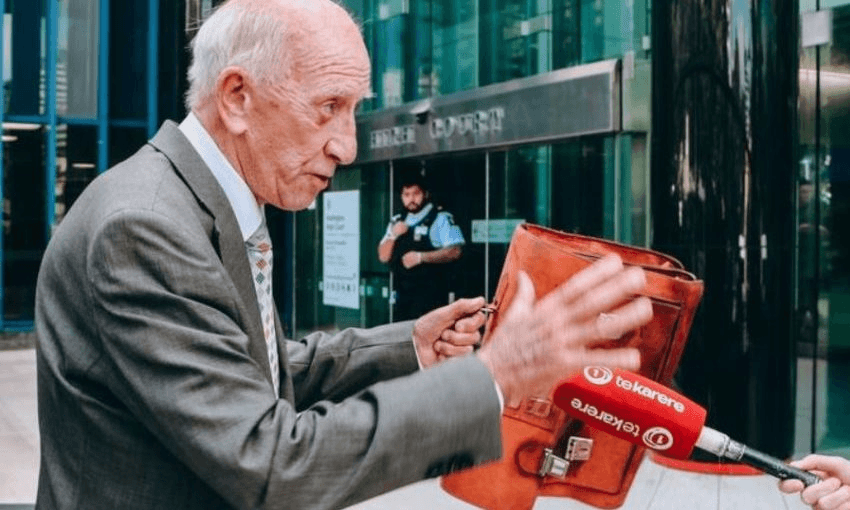

The high-profile case at the Wellington High Court has come to an early halt after lawyers for Bob Jones, who was suing writer and director Renae Maihi, announced they will no longer continue.

Sir Bob Jones was suing Renae Maihi for defamation after she presented a petition to parliament in 2018 to strip Jones of his knighthood for a column he penned calling for Waitangi Day to be renamed “Māori Gratitude Day“. He said she defamed him by characterising him as a racist, and the column as hate speech. The petition has now been signed by more than 90,000 people.

Jones wasn’t seeking damages, but for the court to rule that Maihi defamed him and award his legal costs. However, after cross-examination of Jones and four of Jones’s witnesses by Maihi’s lawyer Davey Salmon, and a statement given by Maihi on Thursday afternoon, the case has been dropped. The defence had not yet begun calling its own witnesses.

Over the course of three days, Salmon cited TV appearances by Jones and numerous examples of his writing from newspapers and books to establish that Jones’s opinions on race relations, specifically his opinions on Māori, have been deemed offensive by many New Zealanders over five decades.

During cross-examination on Wednesday, Jones described the haka as “infantile”, called Māori oratory traditions “bullshit” and described Māori arts as “unaccomplished” and consisting “entirely of wood carving”. He also claimed te reo Māori had been saved from extinction only because it was recorded in writing by early settlers.

Jones promptly left the court after his cross-examination on Wednesday, and didn’t stay to hear evidence from his own witness, NZ First chief of staff Jon Johansson. He did not return to court on Thursday, day four of the trial, to hear evidence from three more of his witnesses, former human rights commissioner Dame Margaret Clarke, author Alan Duff and personal trainer Ryan Wall.

He also wasn’t present when Maihi gave her statement on Thursday afternoon.

A large group of whānau and supporters were there to hear Maihi’s statement, with many crowding outside the courtroom, where the gallery was full. One supporter described her as “brave and dignified” and said her words were “very moving”. He noted that tears were shed by some in the public gallery. When she finished she was met with applause and karanga.

Maihi wasn’t cross-examined by Jones’s lawyers. Instead the court adjourned early. The announcement that the trial wouldn’t continue was made on Friday morning.

A statement by Jones sent to media at midday on Friday stated:

“I filed these proceedings because I was deeply offended by Ms Maihi’s allegations. I am not a racist.

“I now accept, however, Ms Maihi’s offence taking was a sincerely held opinion. The parties may never align on what is acceptable humour, however, no malice was intended by either, thus it is sensible to put an end to proceedings.”

In a later media statement from Maihi, she said:

“This has always been about highlighting the harm and impact that racist language has, both now and historically. It is important for us all to remember that language and articles of this nature, whether intentional or not, can and do cause hurt.

“It is important too that those on the receiving end of racism have an opportunity to express their feelings.

“While I and many others disagree strongly with the language Sir Robert has used about Māori, we can disagree with him without being rude about him as a person. I ask people to keep this in mind when posting on social media.”

This story was updated to include media statements from both parties at 6pm 14 February.

Related:

Leonie Hayden: Bob Jones is not just a racist. He’s also a coward