Richard Dawkins dismisses it as myth, but Māori knowledge is opening up exciting new areas of scientific exploration, as AUT’s Ella Henry explains.

The recent news that Oxford University emeritus professor Richard Dawkins will visit Aotearoa New Zealand next February for a multi-city speaking tour has reignited smouldering flames of acrimony. At issue was Dawkins’ description of mātauranga Māori – Māori knowledge systems – as “myth”, not science.

I was asked by various media to respond to this dismissal and was happy to do so, citing thousands of years of innovative, applicable, and evidence-based knowledge that inform indigenous approaches to science. Since my comments were published, I have received numerous criticisms, not just about me personally, but about “Māoris” [sic], our history, our culture and our knowledge systems.

While it’s easy to ignore the thinly veiled racism that underpins much of the feedback, it’s important that people understand the complexities of mātauranga Māori – what it is, what it isn’t, and how it contributes to global bodies of knowledge, including science.

Here I answer a few of the most common questions about mātauranga Māori, and the concept of Indigenous knowledge as a whole.

Is mātauranga Māori even a thing?

Yes. Indigenous peoples and traditional knowledge are recognised by the United Nations, including the knowledge systems of peoples across Africa, Asia, Europe, Australasia, from the Arctic to the Pacific. New Zealand is a signatory to UNDRIP, which affirms the rights of Indigenous Peoples and our traditional knowledge. These knowledge systems, which include mātauranga Māori, have evolved over many thousands of years, to maintain the sustainability of wellbeing of Indigenous peoples.

So do people working within mātauranga Māori operate outside of accepted science processes?

Those who work with mātauranga Māori apply Māori knowledge to solve a variety of problems. For example, the wahakura is a woven flax bassinet to address the problem of sudden unexpected death in infancy by creating a safe shared sleeping space for babies in their parents’ bed, which has now been adopted by a number of DHBs who distribute them to new mothers.

Richard Dawkins says science is, by definition, “global truth” – but the “truth” of mātauranga Māori is specific to New Zealand. So, how can it be science?

Science is founded on systematic studies of the physical and natural world, through observation and experimentation. Traditional scientific methods are often founded on quantitative, logico-rational, positivist approaches to observation and experimentation, but these are not the only ways to gather, analyse and apply knowledge. The incorporation of traditional Indigenous knowledge with traditional Western science is resulting in exciting and innovative strategies founded on traditional ecological knowledge, local knowledge, folk knowledge, and tacit knowledge. These terms are derived from the systematic observation and experimentation conducted for, with, and by local communities.

So can you give some real-life examples of mātauranga Māori?

The Māori practice of navigation by the stars has been validated by numerous waka voyages around the world; Professor Rangi Matamua, meanwhile, an expert on Māori astronomy, is the first Māori to win the Prime Minister’s Science Prize.

Some more examples: Dr Shaun Awatere leads a group scientists at the helm of research on the Sustainable Seas National Science Challenge; the work of Professor Chellie Smith on Māori leadership is being used by multiple organisations, not just Māori; Professor Rawinia Higgins is renowned for her research on the revitalisation of te reo and was recently elected to the UN Global Taskforce for the Decade for Indigenous Languages that begins in 2022; and Professor Jarrod Haar is a leading expert in business, with his focus on work and organisational studies. These scholars are guided by the melding of Māori and other sciences, not myth.

Are any of the world’s respected scientific journals publishing research about mātauranga Māori?

Yes. The previously named scholars, and others, have published their research in high-impact academic journals, too numerous to mention within the scope of this article.

Is the argument around traditional knowledge versus scientific knowledge specific to Aotearoa New Zealand?

This debate is not only occurring in Aotearoa New Zealand, but among many other Indigenous peoples in countries that include Canada, the United States, and Australia. We can see the impact of this debate in a number of sectors. Within our own education sector, for example, we can cite the changes to how NZ history will be taught in schools, the growing recognition that Māori history and knowledge make vital contributions to New Zealand society, and the growing body of scholarship that is unique to our country. These widespread changes reflect how traditional Māori knowledge is accepted as scientific knowledge by the education sector.

Would it be so bad to describe mātauranga Māori as “myth”? Myth has an important role to play in society, along with science.

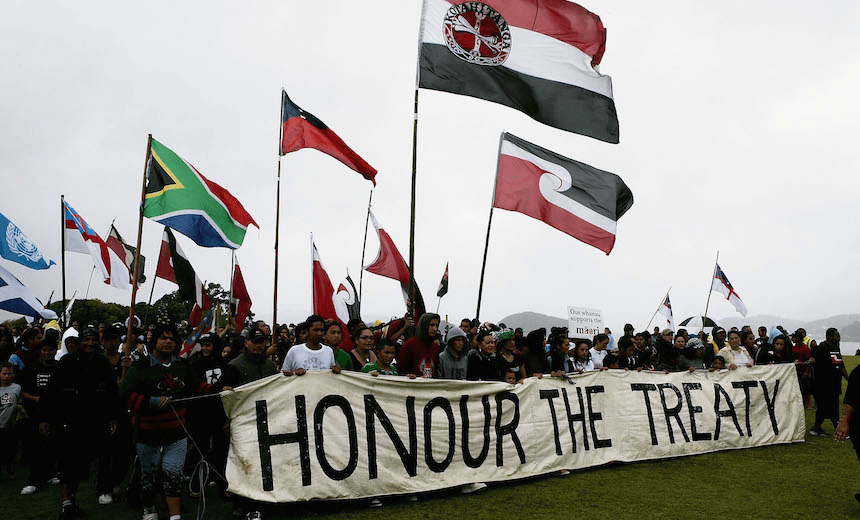

Myth has long been used to describe, interpret and explain mysterious or seemingly unexplainable phenomena, with little “proof” beyond the powers of traditional storytelling. In contrast, while mātauranga Māori might not be the science that takes humans to Mars, it is the science that informs and uplifts Māori communities that have not fared well under the auspices of traditional science since its wholesale introduction after we became a British colony in 1840.

That science, which applied notions of eugenics to the assimilation of Māori, military strategy and might to the invasion and dispossession of our lands, and political science that legalised confiscation and invasion, was an aspect of our history that has been ignored for decades. Mātauranga Māori is not replacing traditional science and the traditional scientific method; rather, it is making space for knowledge that was denied, almost to extinction.

What do you say to those who still question the validity of mātauranga Māori as science?

I am immensely proud to work alongside researchers, scientists and scholars, from a wide range of disciplines and cultural backgrounds, nationally and internationally, who do not feel in any way intimidated by a resurgence of mātauranga Māori. I believe they genuinely feel that our traditional knowledge adds new dimensions to their research in health, architecture, business, finance, ecology, construction, policy and planning. That is what I hope mātauranga Māori can add to the realm of science, here and globally, by adding to, not diminishing, the strength and resilience of the scientific method.