Is there something to be learned from TVNZ’s Wild West-meets-WWE-meets-19th-century-New Zealand web series? After all, writes Sharon Mazer, colonisation, like professional wrestling, is a fixed match.

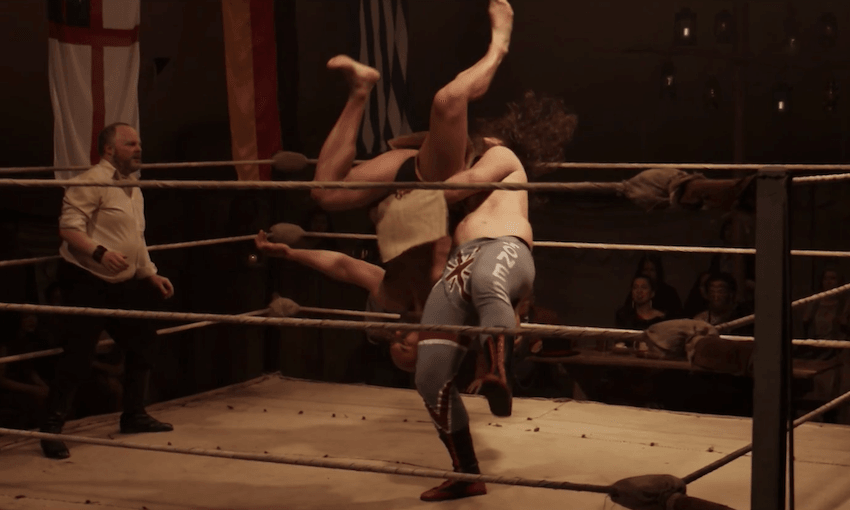

The premise underlying TVNZ’s new web series Colonial Combat is anachronistic and preposterous, even by WWE standards. It’s also fascinating.

Transported from American popular culture to New Zealand as a kind of Wild West meets the World Wrestling Entertainment, Colonial Combat promises to show us, in the producers’ words: “a dog eat dog world, where colourful characters compete inside and outside of the ring”.

And so it does.

Professional wrestling is an unsporting sport. The guy with the money decides who wins, who loses, and on what terms. Justice turns a blind eye, and virtue is no guarantee of success – in fact it’s often the opposite. To envision wrestling matches between Māori and Pākehā in 1836 at the pivotal moment in the history of colonisation would seem to make light of the appropriation of land and consequential erosion of Māori language and culture.

But perhaps there is something to be learned by upending postcolonial pieties in this way. After all, like professional wrestling, colonialism was a fixed fight that carried with it a certain degree of con artistry – a this-for-that promise that proved less than reciprocal.

At its best, professional wrestling is a way of telling a story according to conventions and traditions that have developed over time to produce social meanings that its audiences are generally conditioned to receive. The display of violence is just that: a display. What appears as antagonism is actually produced through the skilled give-and-take between the wrestlers, who take turns looking as though they’re on top of the game. Each must demonstrate the potential to win for the end to be convincing; each must also be convincing in demonstrating their potential to lose. It takes real psychophysical discipline to look like you’re beating someone up without causing injury, and even more discipline to make a show of your body being in pain when it is not.

To plant the wrestlers’ ring on these shores in the 19th century is to reinvent the colonial encounter as a kind of level playing field. Because both sides are shown to be smart and onto the con artistry of the game, the fight in Colonial Combat appears more cooperative than fixed in the usual way. The series invites us to watch the wrestling while forgetting the forces that were at play historically and in the present. Perhaps the conflict between the British and the Māori was only skin-deep, its shape and outcome determined in advance by an unseen powerful figure. The question of who the colonial equivalent of WWE promoter Vince McMahon might have been remains unasked.

Colonial Combat’s performative re-envisioning of the contest between European and Māori capitalises on the fakery of professional wrestling. In so doing, it allows us to imagine that the injuries inflicted during the first stages of colonisation were somehow less real than we have been led to believe. Like professional wrestlers, the colonised and the coloniser might only appear to have been opposed. Historical fact becomes a performative sleight of hand. There might have been a problem with colonisation, but we won’t see that here.

In the world of the series, wrestling appears as a harmless diversion from the serious business of colonisation. Watching wrestling – whether set into the colonial period or nowadays – is a distraction that relieves us from paying attention to the way real conflicts are playing out in the world around us. In establishing an ahistorical equivocation between wrestling and colonisation, Colonial Combat risks displacing the matter at hand: the contest for land and the question of who, really, might have the power to determine the future of Aotearoa.

Sharon Mazer is professor of theatre and performance studies in Te Ara Poutama, AUT’s faculty of Māori and indigenous development, and the author of Professional Wrestling: Sport and Spectacle.