A new report suggests a focus on export industries will provide the best opportunity for growth in an expanding Māori economy.

The Māori economy is at a turning point, with rapid growth, a diversifying asset base and untapped export potential creating new opportunities. But despite nearly doubling in five years – from $17bn in 2018 to $32bn in 2023 – significant challenges remain, particularly in closing the gap between Māori and non-Māori in skilled employment and income levels.

The Māori economy has surpassed its estimated $100bn milestone years ahead of a 2030 forecast. Of the $126bn in assets, $66bn belongs to Māori businesses, $19bn to self-employed individuals, and $41bn to Māori trusts and collectives. The number of Māori-owned businesses has grown to 23,748, up 7% since 2018, with the workforce expanding by 19% to 390,700 workers.

Once dominated by agriculture, forestry and fishing, the Māori economy is diversifying. In 2023, professional, scientific, and technical services became the largest Māori GDP contributor at $5.1bn, followed by real estate ($4.1bn) and administrative services ($4.2bn). While primary industries remain vital, particularly for iwi, the shift toward high-skilled, knowledge-based sectors signals a transformation.

“Māori economic activity is moving up the value chain,” economist Hillmarè Schulze told a crowd gathered at Eden Park for the Auckland launch of the report late last week. She highlighted horticulture, technology, and manufacturing as sectors with significant export potential. Tama Potaka, minister of Māori development agreed, emphasising that future growth will come from Māori youth leveraging professional expertise and global markets.

Industries currently contributing less than $1bn to Māori GDP include wholesale trade, retail and accommodation, information, media, and telecommunications, and arts and recreation services. Schulze identified these sectors as key areas for expansion, particularly due to their export potential. She emphasised that Māori businesses should focus on growing international markets, leveraging unique cultural branding, and securing more trade opportunities to drive further economic growth.

Self-employed Māori increased 49% and Māori employers grew 31% since 2018, reflecting a surge in entrepreneurship. For the first time, more Māori workers hold high-skilled jobs (46%) than low-skilled jobs (40%), a shift driven by greater participation in professional industries.

Despite these gains, Māori remain underrepresented in high-paying roles and boardrooms. Non-Māori workers still dominate high-skilled occupations (57%), highlighting an ongoing gap in access to leadership and specialist careers. This imbalance is reflected in income disparities – Māori employers earn nearly $80,000 on average, but a significantly lower proportion of Māori hold those positions compared to non-Māori. Potaka stresses the importance of education and mentorship to retain and develop Māori talent within Aotearoa.

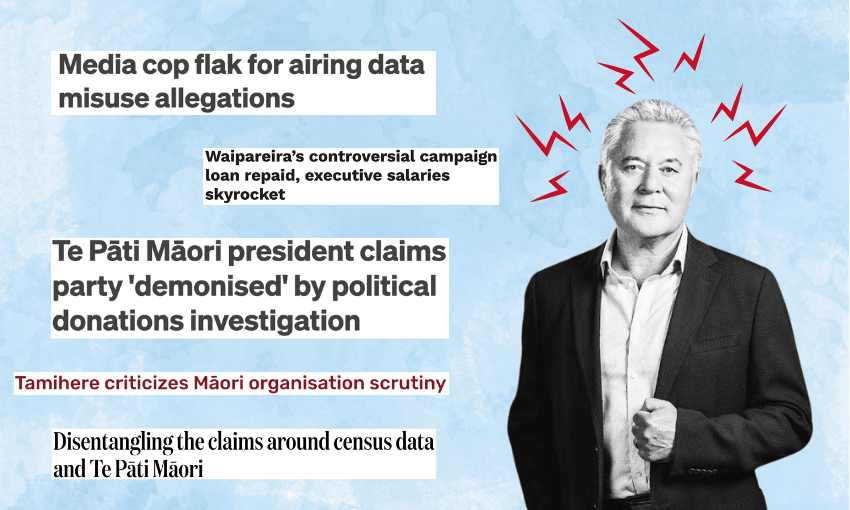

A key factor in the reported economic surge is improved data collection, with Schulze estimating that 20-30% of the growth stems from better measurement rather than entirely new economic activity. The latest report integrates data from Te Matapaeroa, census records, and Māori Land Court valuations, painting a clearer picture of Māori contributions.

“Māori businesses were always contributing more than previously measured. Now, we have the numbers to back it up,” Schulze explains.

Māori businesses continue to prioritise whakapapa, kaitiakitanga, and intergenerational wealth over short-term profit. Speaking to the media last week, Helmut Modlik, chief executive at Te Rūnanga o Toa Rangatira, described iwi investments as long-term and community-focused: “We invest to sustain our people and whenua, not just to generate returns.”

This values-driven approach has become a competitive advantage, particularly in branding and export markets. The global demand for indigenous authenticity is fueling Māori business expansion, from manuka honey to high-end Māori-designed tech and creative enterprises.

While growth is undeniable, economic disparities remain. Māori home ownership (52%) still lags behind non-Māori (67%), and Māori households rely more on government support. Access to capital is another barrier, with Adrian Orr, Reserve Bank governor, calling the financial sector’s lack of Māori-inclusive lending models “disappointing.”

The government has launched whenua Māori lending reforms to make it easier for Māori landowners to secure financing, and iwi-led funds like Rauawa are working to bridge Māori investors with lenders. However, banks and policymakers must do more to ensure Māori businesses have the capital needed to scale.

As the Māori economy continues to expand, the challenge is ensuring this growth delivers real benefits for whānau and communities. Investment in education, innovation, and capital accessibility will be crucial in sustaining momentum. Strengthening pathways for Māori into high-value industries, global markets, and leadership roles can accelerate not only Māori success but Aotearoa’s broader economic prosperity.

Schulze believes the Māori economy could double again by the late 2020s, as long as structural barriers are addressed. The expansion of Māori businesses into export-driven sectors will be key, alongside leveraging cultural identity as a competitive strength.

The Māori economy is no longer a niche contributor – it is a powerful, growing pillar of New Zealand’s economic future. With strong leadership, inclusive policies, and a focus on long-term prosperity, it has the potential to drive transformational change for generations to come.

This is Public Interest Journalism funded by NZ On Air.