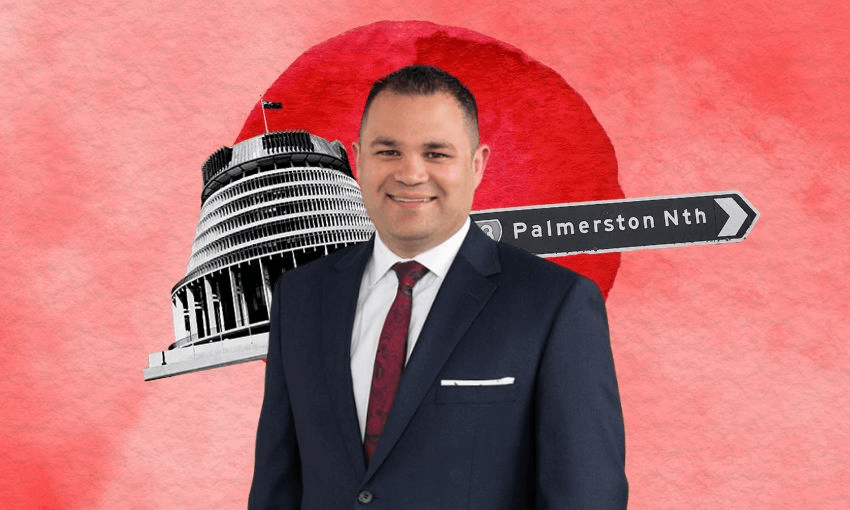

The Labour Party’s Tangi Utikere is Palmerston North’s biggest champion and an MP on the come-up.

There’s an ancient adage familiar to Palmerstonians (as in, people from Palmerston North), uttered by a British explorer after a voyage through the land of the long white cloud: “if you wish to kill yourself but lack the courage to, I think a visit to Palmerston North will do the trick”.

Those immortal words were spoken by Monty Python comedian John Cleese, and they continue to haunt the city to this day, mostly in the form of a landfill bearing Cleese’s name. If you’re a Palmy native, you’d see it as just another slight on an already misunderstood place (or “suicide capital of New Zealand”, as Cleese described it). If you’re the local MP Tangi Utikere, it’s the perfect benchmark to prove the community is only on the up and up.

“You know, there was a famous quote about Palmerston North…,” Utikere laughs in conversation with The Spinoff. Sure, the city chucked up a sign around the rubbish dump to commemorate the moment, but it doth not make the city. “This is a fantastic community that has everything that anybody ever needs,” he says. “Once you visit this place, you know how special it is”.

Palmy born and bred Utikere, whose whakapapa extends to the Cook Islands, is the Labour Party’s new rising star. He’s the only MP who managed to make a significant leap forward in Chris Hipkins’ shadow cabinet in a reshuffle in early March, jumping from 19 to 12 on the party list and picking up two shiny new portfolios – local government and small business – along the way.

A member of the Labour class of 2020, Utikere has made a name for himself as a sharp question time stickler in his role as transport spokesperson and a man who can hold his own through general debates, the makings of a potential frontbencher.

His taste for politics was passed down by his great uncle Tai, who was “heavily involved” in the Labour Party and who introduced a teenaged Utikere to his first public meeting. “He picked me up every Monday night, and we would go to our local Labour electorate committee meetings,” Utikere says. “As someone who came to this country with no formal qualifications – same with my grandparents, same with my parents – there was only one option [in politics], and they gladly supported the Labour Party.”

It was 1995, and Palmy locals Steve Maharey and Jill White were building hype for their Labour campaign in the coming year’s election, which would see Maharey retain his role as Palmerston North MP while the party would lose on the whole. In 1997, Utikere became White’s youth MP, and in 1999, Maharey’s re-election was the first Labour campaign Utikere worked on, aged 19.

While Labour lost a number of reliably red seats in the 2023 election – Wellington Central, New Lynn and Mt Roskill, to name a few – Utikere was able to retain Palmerston North for the party. He first became the local MP in 2020, and though the 2023 election saw a tighter race between the Labour candidate and National’s Ankit Bansal (3,087 votes apart, much smaller than the 12,508 margin in 2020), the electorate has remained a Labour stronghold since 1978.

Being heavily involved with the community certainly helps. Utikere was Palmerston North District Council’s first ever Pasifika member when he was elected in 2010, and was the first person of non-European descent to be elected deputy mayor. Yeah, it says a lot about Palmy, but Utikere promises the city is also home to an “extremely diverse” community encompassing around 130 ethnicities and 220 languages.

While they’re “certainly not a South Auckland in terms of numbers”, Palmy’s Pasifika community is still a stronghold, Utikere says. “When I was on the council, it was a real focus of mine to ensure that there was resource and funding [for the Pasifika community],” Utikere says. There’s now a Pasifika Community Trust, and the council agreed in late 2023 to invest in a community hub over the next two to three years, which will cater to the city’s growing Polynesian population. “We’ve come a long way, and I’m pretty proud of our achievements in that space.”

These days, Utikere’s time is split between parliament, which begs for his presence in Wellington for the 82-or so sitting days every year, and Palmy, where days are focused on talks with constituents and appearances across the city. There’s the trips to schools, where the teachers still remember the child version of Utikere, who used to swim in the pool and make soup to sell at the school canteen for 50 cents.

“Connections that you have [are what] I absolutely love being the local member for,” he says. “I was born here, I’ve lived here all my life. Not much goes on here without people knowing about it.”

It also helps to genuinely care for your city, and in Utikere’s eyes, there’s a lot to love about Palmy, like a stroll along the Manawatū River or a trip to Café Jacko, where the servers behind the counter know his order (“coconut chai, and you can’t go past mince on toast”). It’s nice to walk down the street, and see “these really fond memories of this community” on just about every corner.

And then there’s the time you still need to carve out for family – such as Utikere’s partner of 20 years Te Rei, an accountant whom he meet-cuted in a supermarket, and his three siblings (he’s the oldest, of course) who are still dotted around Palmy. “It’s quite nice to have someone who can choose what he wants to involve himself in,” Utikere says of his partner. “This is my job, but it’s not our life.”

For now, it’s back to parliament, where Utikere will inevitably exchange a war of words with transport minister Chris Bishop and local government minister Simon Watts in question time, and also buckle down to hunt for a youth MP who may, as he eventually did with White, follow his footsteps all the way to a spot behind a bench in the House of Representatives.

It’s an opportunity for a young person to be mentored and learn about Aotearoa’s democracy up close, but it’s also offered Utikere a chance to hear about issues in the city and across the country which affect a demography typically uninterested in local government: rangatahi. “Some [young people] are really concerned about the lack of engagement they have with their community … [and] having decision-makers that are prepared to listen to what they have to say,” Utikere says.

Bridging the gap between councils and their younger communities is a matter Utikere hopes to address as Labour’s new local government spokesperson, as well as a few other issues. Such as the government’s hard line on councils “getting back to basics” and ditching the “nice-to-haves” in the last year, whereas Utikere says that in his experience, it’s more about striking a balance.

Just as important as ensuring a city can function properly with its working basics – water, roads and infrastructure, for example – is creating a city that has a “vibrant [community] with whole heart”. So-called basics and nice-to-haves are “equally important” for communities to grow and thrive, Utikere says.

It’s repairing these relationships between local and central government, and giving more autonomy to the former, that Utikere is looking forward to in his new role which, if recent polls are anything to go by, might see him one day become the minister for local government. “For me, it’s about partnership, and making sure decisions are taken at a local level,” Utikere says. “I don’t think it’s right that local government just constantly seems to be landed with mandate after mandate, and they’re expected by central government to pick up the tab for all of that.

“What councils need is to be working alongside the government, instead of being told what to do,” Utikere says. “That’s going to be a real focus for me.”