Dr Asim Qureshi, a counter-terrorism expert and author of Rules of the Game: Detention, Deportation, Disappearance, writes about his time in New Zealand and the importance of remembering colonial violence in the narrative around the terrorist attacks in Christchurch.

In November 2018, I was invited for the first time to take part in a conference in Auckland, New Zealand by the Khadija Leadership Network. The conference aimed at providing young Muslims the space to think about their identity at a time of growing hostility to Muslims and Islam. My own talk very much focused on the idea of empowerment, and what it means to own your own narrative at a time when Muslims are continually constructed as threats by national and international media.

The conference was an incredible experience for me, as I met with members of the Māori Muslim community whose strength and sense of personal and community dignity I was immediately drawn to. Over the course of my short time in New Zealand, I took the opportunity to sit with them and listen to their concerns about the struggles they have had as Māori resisting the colonisation of their lands and culture, but also as Muslims who are misunderstood in their cultural practices.

The conference presented a wide range of divergent opinions, some I agreed with, others less so. There was one talk that particularly stood out for me, by Dr John Battersby, from the Centre for Defence and Security Studies at Massey University. Battersby is someone who has engaged in countering-violent extremism (CVE) programmes, that essentially operate in what is euphemistically termed the ‘pre-criminal space’. In other words, CVE practitioners and so-called experts, presently operate in an environment that terrorism can be pathologised, and stopped before it can manifest.

His presentation at the conference very much focused on what he described as a history of terrorism in New Zealand. As I sat there, sitting and listening through the very interesting and wide range of examples he included as part of his analysis of ‘terrorist’ activity, which he would sometimes refer to as politically motivated violence, a sense of real unease began to grow in me. As the talk went on, I could see on the face of others in the crowd that they too, felt uncomfortable with much of the framing that was taking place.

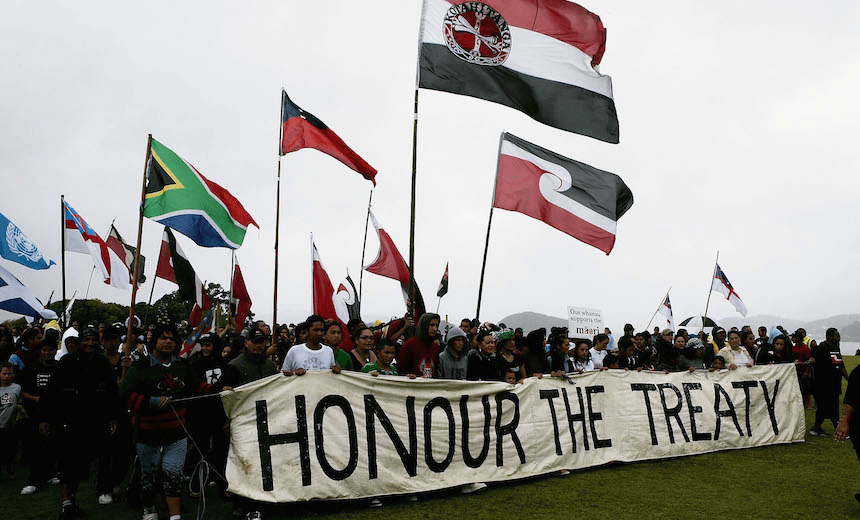

At the end of the presentation, I asked one simple question to Dr Battersby. Why had he chosen to focus on the 1970s as the start of terrorist violence? At first, he seemed somewhat perplexed by the question, with his explanation being that one needed to start somewhere in history, and he had chosen this period in particular. An exchange began between us, where I attempted to explain that he is an actor in the construction of this knowledge, and so he cannot simply say that he arbitrarily chose to start there, without justifying his decision. Ultimately, I was driving him towards accepting that he was wilfully blind in refusing to include colonial violence against Māori within his construction of terroristic violence within the history of New Zealand. This wasn’t just to set the matter of history correct – the entire purpose of my intervention was to highlight how his presentation distorted our ideas of how we understand contemporary issues, particularly in relation to terrorism.

One of the gifts I received from the Muslim community of New Zealand before my departure was a copy of Dr Ranginui Walker’s Ka Whawhai Tonu Matou/Struggle Without End, one of the most complete histories of the Māori struggle against colonialism and colonialism in New Zealand. As Walker reminds us in his book:

“The outcomes of colonisation by the turn of the century was impoverishment of the Maori, marginalisation of the elders and chiefly authority and a structural relationship of Pakeha [white] dominance and Maori subjection. So total was Pakeha dominance at a time when the Maori population had fallen to its lowest point of 45,549, that the coloniser deluded himself into thinking he had created a unified nation state of one people whereby amalgamation of the races would resolve once and for all the problem of the Maori.”

The book in many ways highlights everything that was wrong with Battersby’s presentation, as it reminds us that violence in New Zealand is nothing exceptional. The current discourse is completely removed from the extreme violence that the nation was built on, and the specific ways in which the history of colonisation is removed from any contemporary significance.

In particular, the book reminds us of the amnesia that permits modern myths about who New Zealanders are today, and the way in which certain populations have been given a privilege of position off the backs of the indigenous population. When violence is committed against that history and embedded within every single structure of the state, then coupled with the politics of problematising Māori and othering Muslims and immigrants, this leads to the structural racism and violence we witness today. This violence does not always manifest itself in killing and mass murder, but the violence is every day. It exists on the streets, in places of employment, in police stations, in courts, in parliament and propagated within the media.

Ultimately, if New Zealand hopes to have any chance of recovery from what it has suffered, then it must first seriously confront its own colonial history, and how that colonial violence continues to be excluded from the foundational myths of New Zealand as a tolerant society.