Nadine Anne Hura has been travelling the country learning about indigenous climate adaptation solutions. She shares some of the insight, inspiration and straight-talking wisdom she picked up along the way.

Lesson 1: Hope is shaped like a shovel and will give you blisters

The day before my brother died, he bought a $5 lucky dip Lotto ticket from the Z service station in Upper Hutt. Then he drove into the hills and never returned.

Sometimes this knowledge sits in the back of my mind doing nothing; a simple arbitrary fact to go along with all the other arbitrary facts collected by the coroner. Other times it drags me from sleep, demanding answers. The question that won’t leave me is why someone would take a punt on a future he’d never get to see.

The same question confronted me over and over again while interviewing Māori researchers for a podcast about indigenous responses to climate change (co-hosted by Ruia Aperahama and funded by the Deep South Challenge, it will be released in March). Everywhere I went, from Ihumātao to Tairāwhiti to Whanganui, I found marae communities invested in work they aren’t likely to witness flourishing fully within their lifetime – let alone personally benefit from. This work includes liberating and restoring wetlands, revitalising ancient food-gathering practices, replanting native forests, establishing anti-capitalist regenerative economies, reclaiming mātauranga, and so much more.

The immensity and cascading nature of the environmental challenges facing Māori communities – coupled with a severe lack of economic resources to respond, while occupying a position of ongoing structural inequity – is overwhelming. More than once I felt like kneeling down. There’s a kind of awe that hits you when you understand the scale of the loss and the commitment required to heal and recover.

Yet, over and over again, people I spoke to reiterated that hope on its own isn’t the thing keeping them going. “Hope is abstract,” Shirley Simmonds of Ngāti Huri told me. She has recently made the move home to Pikitū with her whānau and is deeply attached to the shovel with which she’s she’s helped to plant the beginnings of a food forest, and also tree seedlings on land that was once – and will eventually again be – blanketed in native ngahere. “Hope needs to be activated through work,” Simmonds said. “Sovereignty is inherently practical. The solutions are within us – kei a tātou te rongoā.”

Similarly, Pania Newton said the fuel that ignites and keeps the kaupapa for justice going at Ihumātao is mana motuhake. “We don’t give much thought about what the government’s doing. We’re just getting on with the mahi that needs to be done by exercising our collective rangatiratanga. The work carries on regardless who’s in government. This is not a new struggle for us, it’s a continuation.”

So that’s the first lesson from the pā harakeke: hope isn’t a passive thing you sit around and wait for. It is pragmatic. It’s sober. To quote Simmonds again: “Me raupā ōku ringa kia whai ai i ngā wawata.”

Or as I like to paraphrase: hope is shaped like a shovel and will give you blisters.

Lesson 2: Myths aren’t for shits and giggles

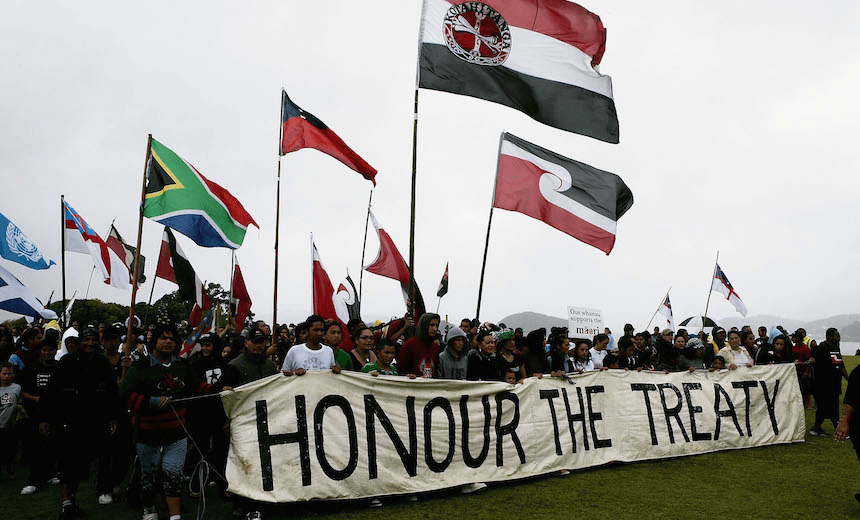

In environmental spaces, you’ll often hear the phrase “climate change is going to hit indigenous communities first and worst”. Invariably, it isn’t Māori saying it. That’s because the climate crisis isn’t imminent. Ever since the arrival of settlers and the signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, marae, hapū and iwi have been responding to catastrophic environmental changes caused by human activities. The only difference now is the consequences have become so widespread and severe, governments can no longer deny it is a crisis.

The tendency to diagnose climate change solely by environmental symptoms – rising seas, extreme weather, drought, biodiversity loss – is a dangerous blind spot. Not only does it position the environment as the enemy, it shifts responsibility for global warming away from those who benefit from the hierarchies that privilege a few at the expense of every other living thing on the planet.

These hierarchies are the same hierarchies that dispossessed Māori of their land, destroyed native forests, subjugated Māori knowledge, and created dependence where once there was sovereignty and self-sufficiency. To put it in plain language: climate change and colonisation share the same whakapapa.

The most visible impacts of climate change in human terms can be seen in the over-representation of Māori in every negative social statistic you care to measure. Yet rarely are these statistics attributed to the climate. This is despite the fact that the social, material and spiritual symptoms of the disconnection between land and people are as relevant as climate indicators as storms and slips and cyclones. The same dis-ease within the climate is reflected within people and communities.

The interdependent relationship between land and people is woven into the fibres of te reo Māori. Introducing yourself in Māori, for example, involves identifying the rivers, lakes and mountains to which you belong and are responsible to. Nowhere is this connection better exemplified than in pūrākau.

While they were historically written off by Pākehā ethnographers as myths, Stacey Bishop is under no illusion about the importance of pūrākau in a climate context. Bishop is one of the Ihumātao researchers gathering oral histories about the climate resilience of the hapū of Te Ahiwaru. “Our tūpuna didn’t have these pūrākau and pakiwaitara for shits and giggles,” Bishop said. “They had a purpose. Our pūrākau hold the keys to our survival.”

Lesson 3: Tangata whenua are adaptation experts, just saying

Although the terminology might be new, if anyone holds expert status in climate change adaptation, by literal definition, it is tangata whenua. Some navigated here by the stars, others originated from the mist, all have survived colonisation.

Yet one of the most devastating and under-acknowledged impacts of human-driven climate change is the threat to centuries of inter-generationally transmitted, highly specific indigenous knowledge. Earliest migration stories, for example, are permeated with insights about the quest for food security across the Pacific – just as conversations are today in a global context.

The difference now is the speed of the changes. That’s why so many Māori climate researchers are heavily and urgently focused on the reclamation and revitalisation of mātauranga relevant to their own whakapapa. Much of this intricate scientific knowledge is still contained intact, ingeniously, within oral narratives.

Tracey Tangihaere, a Ngāti Maru researcher based in Tairāwhiti, referenced an example from oral history that reinforces the ancestral link between land and people: “When your pūrākau talk about being the people of a thousand fishes, but there are no fish anywhere, you know that’s a sign. The next question is, how do we get those thousand fishes back?”

For Bishop, despite the excitement of reclaiming indigenous knowledge, there’s a painful irony to the process. “For people to come in 180 years ago and say ‘we know this land because this is how it works in the country we come from’ is ludicrous. Our people had been living on this land for over a thousand years. Our tūpuna knew this land better than anyone.”

Tracey Tangihaere, a Ngāti Maru researcher based in Tairāwhiti

Lesson 4: Talking about climate change is like walking around with your head in the clouds

The closer you get to the pā harakeke, the less likely you are to hear the words climate change. One researcher told me that the surest way to guarantee no one shows up to your wānanga is to put climate change in the title. It is a term that can be more intimidating and confusing than enlightening. But if the wānanga is about restoring the mussel beds, or helping develop a locally specific maramataka, or physically retracing the steps of an ancestor or weaving hīnaki, everyone wants to be there.

The more prominent words you’ll hear during these wānanga relate to the interconnectedness of te taiao. Many of these concepts don’t have natural equivalences in English, such as mauri, tohu, atua, kaitiaki, maramataka, mahinga kai and taonga. Talking about te huringa o te āhua o Rangi, or “the changing appearance of the climate”, while ignoring Papatūānuku and all other atua is like – I can’t resist – walking around with your head in the clouds.

More seriously, mainstream conversations about climate change by default privilege western scientific knowledge. As a discipline, not to mention as linguistic shorthand, climate change relegates all other knowledge systems to a position of deficit. This is how climate change as a movement can itself be recolonising. It forces mātauranga Māori to define itself according to what it is not.

For example, Bishop said that when people call for an end to climate change she hears resistance to te taiao taking the natural course required to heal itself. “The atua are doing what they need to do to rebalance themselves. Humans have done some kūare things and that’s affecting our quality of life. The consequences are drastic because the impact of human behaviour has been drastic.”

Although the situation is dire, especially considering the speed of biodiversity and species loss, defining the causes and symptoms of climate change differently opens the door to some revelatory adaptation possibilities. To begin with, the forecast isn’t all doom.

Lesson 5: Forecast for adaptation = abundance

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the challenges of adapting to climate change with limited resources over successive generations has, for many Māori communities, been galvanising. The struggle without end has developed resilience, rewarded resistance and perseverance, fuelled creativity and inspired innovation. The establishment of kōhanga reo more than 40 years ago is one example. Through a climate lens, Hana Rāwhiti Maipi-Clarke’s maiden speech to parliament last year is surely the epitome of intergenerational climate adaptation planning.

Every direction you turn, the mokopuna investment policy is maturing. Whaea Ruthana Begbie, Shirley Simmonds’ aunty, recalled the occasion her mokos presented Te Arohirohi o Raukawa, the freshwater assessment tool they helped develop as interns with Raukawa. Begbie explains: “I just couldn’t stop crying because it was like, why were we denied the right to know all this about ourselves and our relationship to our awa? I was getting angry learning about how the river had become so unhealthy and who made it that way, but then I thought, well, I am fortunate because I am getting the education now through the eyes and ears of my mokopuna.” She laughed, then added: “and then I cried even more!”

In Whanganui, the same inspiration is reflected in Te Morehu Whenua’s research team, whose members are as young as five. These tamariki and rangatahi joined the environmental group at Rānana Marae – more than an hour up river, off-grid – so that they could learn how to eel. Four years later, they can identify dozens of different species, monitor the health of their habitats including climate threats, and observe and enforce sustainable customary gathering practices. Not only that, they regularly rock up to climate conferences or dial into Zooms with water quality experts, fully invested in every scrap of data and information that can help them look after the river that looks after them. The grown-up scientists often do a double-take, before understanding that this is the literal embodiment of Māori climate adaptation planning.

Rāwiri Tinirau, Te Morehu Whenua’s research team lead, explained the genius: “The tuna called them home, but it’s not just about having fun. They’re also learning the skills they need to ensure they will never go hungry.”

Moving away from the pā harakeke back to climate conferences is jarring. It isn’t uncommon to hear people expressing feelings of anxiety, fear and despondency. There is also a pervading belief among ordinary people that one person alone is too insignificant to make a difference to climate change, so what’s the point?

Climate adaptation researchers from Te Weu Tairāwhiti have invested hours and weeks and years proving the counterfactual. They haven’t just imagined a future beyond economies of profit, they’ve proven they work and can articulate why.

The East Coast Exchange, developed in the days following Cyclone Gabrielle, is just one example of an indigenous adaptation solution that pairs the spirit of crowd-sourcing with the assistive power of technology, for the benefit of people and the planet. The East Coast Exchange works because it turns out people are more motivated by love than by fear and anxiety. The regenerative, flipped economy is fueled not by competition and scarcity, but by reciprocity. The currency is manaakitanga, the result is abundance.

There’s also relief in knowing that individuals alone are not expected to carry the burden of responsibility to fix the mess. As Qiane Matata-Sipu, who works with Bishop and Newton in the Te Ahiwaru team, said: “We forget that the atua made us. We are the pōtiki. That’s the essence of the whakatauki ‘whatungarongaro te tangata, toitū te whenua’. We could all drop dead tomorrow and these things will thrive without us. We are the ones who need the whenua and the moana and the awa, not the other way around. That’s why it’s a bit egotistical to say we’re going to help the atua, because it’s us who need their awhi. We are the ones who need healing. Our mental wellbeing, every thread of our being, is tied into the health of te taiao.”

I really believe this to be true. When I wake up thinking about my brother stopping at the Z service station before heading over the hills with a single uncashed lotto ticket in his glove box, I imagine being able to tell him the most important climate lesson of all: that when we restore our connection to land and to people, we heal ourselves.

Public Interest Journalism funded by NZ On Air.