Worth billions of dollars, the Māori economy is creating intergenerational wealth. But the rising tide isn’t lifting all boats. Researchers at Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga are detailing how the ‘taniwha’ economy can be a better force for good.

They say taniwha live in the deep. kaitiaki of our moana and awa, they guard against malice and serve as auspicious tohu – respected as protectors of some iwi and hapū, and feared by many for this same reason. We must walk gently through the world, their presence suggests, for they are capable of good and ill will. A capricious, complex power taniwha are to Māori.

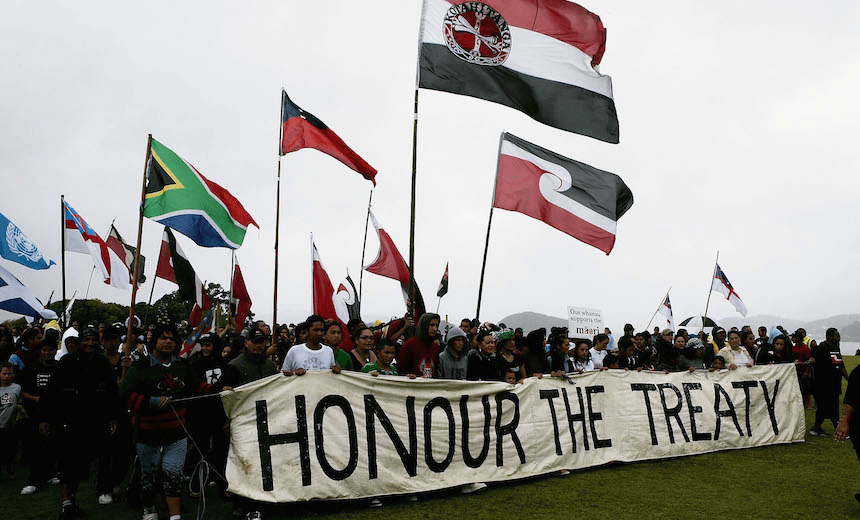

The Māori economy is often described as a “waking” taniwha worth an estimated $70bn based on the value of its collective assets – up from $16bn two decades ago. Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei, Waikato-Tainui, Ngāi Tahu and other iwi immediately come to mind as its heavyweight players, having grown their multimillion-dollar Te Tiriti o Waitangi settlements – only fractions of the value of the whenua that was taken – into portfolios worth billions of dollars of wealth. And its traditional base of industries, the “three Fs” of farming, fishing and forestry, has been supplemented by real estate and property, manufacturing and other sectors. Since 2012, Māori-owned assets have increased in value by 10% each year – much faster than the wider Aotearoa New Zealand economy.

Healthy, successful, thriving – that’s how the taniwha economy appears. But it remains shackled by colonial chains. As Professor Te Maire Tau (Ngāi Tūāhuriri) and Dr Matthew Rout of the Ngāi Tahu Centre, a joint initiative between the South Island iwi and University of Canterbury, explain: “No tribal organisation exists in Aotearoa today with any capacity to tax, nor the right to establish any local bylaw or regulation over its land. Economies exist when supporting institutions are created with the power to regulate property and to tax. This fact quite bluntly challenges anything the Crown has considered for Māori in the era of Treaty settlements, and it also challenges the modern orthodoxy of what constitutes a Māori economy.”

Put simply, no Māori economy can exist without the requisite political power to constitute and regulate an economy. While iwi have generated billions through their holdings corporations – themselves a form of colonial construct – which they have invested in social welfare, cultural revitalisation initiatives and environmental restoration, they are not able to provide a safety net for all their members. It is the Crown that has the revenue and regulatory capacity.

“He taniwha kei te haere mai, ona niho he hiriwa he kōura ko tona kai he whenua. Kaua e mataku i te hiriwa me te kōura, engari kaua e tukua i te hiriwa me te kōura hei atuatanga mou.” So says Aperahama Taonui, a visionary 19th-century leader of the Te Popoto hapū of Ngāpuhi. A taniwha with teeth of silver and gold is on its way, he cautions. Do not fear the teeth of silver and gold; just don’t allow it to become your god.

The whakatauākī is apt, says Professor Chellie Spiller (Ngāti Kahungunu ki Wairoa). The Māori economy may be lauded for all its “glittering valuations”, but they mask “seeds of discontent”. Economic benefits aren’t necessarily passing through to Māori who are twice as likely to be unemployed as non-Māori, twice as likely to rent and twice as likely to receive income support. “The idea that a rising tide lifts all boats doesn’t necessarily hold true,” Spiller says.

Should Māori have cause to celebrate then, given the taniwha economy operates in and is restrained by an institutional framework so different from te ao Māori? Are there alternative pathways that rightly demonstrate the waking taniwha is a force for good? Spiller, a professor of management and leadership at Waikato University and part of a team of researchers at Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga (NPM), is struck by these pātai. The NPM scholarship on Māori wellbeing economies has conceptualised a truer ideal of the waking taniwha around effective Māori leadership and decision-making, Māori environmental economics, and whānau as the core source of wellbeing. Guided by mātauranga and the principles of te ao Māori, the researchers are using the past to guide them in carving a pathway toward a goal Māori share – mana motuhake.

Leadership and decision-making

Good Māori leaders are physically healthy, mentally sharp, emotionally aware, and spiritually and culturally grounded, according to NPM’s report on effective leadership and decision-making. They weave leadership throughout their collectives, stand steadfast in the face of other agendas, and communicate clearly. Good consensus decision-making is a mirror image of effective leadership. Māori do it tika by seeking full and active input from all generations, promoting kotahitanga, which “hold[s] diversity in unity”, and recognising decision-making has importance, as does the final destination.

However, “reality is difficult”. Colonising processes and attitudes can alter Māori ways of doing and being, and the friction between culturally grounded values and commercial imperatives has a “long, relentless and thorny history”. Good Māori leaders are capable of seeing beyond the existing reality to fully realise everyone’s potential, much like how Tāne and his siblings ushered in te ao Mārama from the long, dark night of their parents’ tight embrace. Similarly, good decision-making works like a healthy kauri tree does – its roots are grounded in a kaupapa to which the collective aspires to nurture; the trunk provides structure and form for facilitating debate and strategy; and the branches and foliage represent individuals “transforming light into energy” and feeding back information for assessment. Effective leadership is affirming, effective decision-making is fortifying. All Māori are capable of both.

Māori and the environment

From Papatūānuku all Māori are born; “whenua” means land and placenta. Māori economic relationships are shaped by that inalienable connection. “Te ao tūroa, te ao hurihuri, te ao mārama – the old world, a changing world, a world of light”, an article written by NPM researchers concludes that Māori have managed to thrive in the settler and global economy, not in spite of an environmentally grounded approach to economics, but because of it.

Refined over the first millennium of inhabitation, before colonisation irrevocably altered the destiny of tangata whenua, the indigenous economic approach asserts humans are embedded within nature. Their relationship is material and spiritual, of which the system for producing goods and services for consumption is just one facet. Māori economics is so ingrained in Papatūānuku, however, that all economic relationships are “simultaneously social, spiritual and ecological”. Māori economics, therefore, is “fundamentally, an environmental economy in conception and practice.”

At its core is kaitiakitanga. The enduring ethic stipulates Māori are obliged to actively protect and guard the mauri, tapū and mana of all their relationships with nature. Such a responsibility is keenly felt within the Māori economy. In a survey of nearly 30 agribusinesses, almost all said that maintaining or enhancing the mauri of the whenua was “extremely important”. Accountability isn’t just tied to ensuring financial viability either – social, cultural and environmental performance make up Māori businesses’ quadruple bottom line reporting.

Acting in accordance with tikanga, the taniwha economy strives to do right by Papatūānuku and her gifts; the health of all relationships it forges and maintains with her; and the generations of whānau for whom wealth is created. The context in which kaitiakitanga is practised may have changed since waka first came ashore in Aotearoa, but the environmental ethics of te ao Māori remain a zenith star. Ngā Pae research leader Professor Spiller and team say: “Economic success does not need to come at the expense of nature, or the human communities that are a part of nature.”

What world awaits Māori?

If the recent past tells Māori anything, it is that change is the only constant. Therefore, forecasting current trends is critical for formulating the foundations of a Māori wellbeing economy. Should today’s macro trends converge by 2050, the future looks grim, says Rout. Climate change, mass extinctions, biodiversity loss, ecosystem collapse, pollution and resource scarcity will have ravaged the world. Conflict within and between states will have grown as an increasingly fractious and faltering international system strains under extreme geopolitical polarisation, existential resource and food shortages, mass forced migrations, intensified economic inequality, resurgent authoritarianism and rampant disinformation. Some 10 billion people will live on Earth, although climate-related events have displaced 12% of them, with metropolitan areas expanding to accommodate nearly two-thirds of the world’s population. Economies will be transformed by the oversized influence of mega-cities and mega-corporations, the weight of ageing populations and ballooning government debt, and the impacts of AI and automation.

One-fifth of New Zealand’s demography will be Māori; they will be younger while the population more generally will be older. Few Māori will own their home. In 30 years, Māori may have to operate in a world fundamentally different from the present. The research centre’s “Te niho o te taniwha” report maps out pathways that are open to Māori – and which could help them thrive, notwithstanding the dire outlook.

One approach that leads to an economy whose financial, social, cultural and environmental benefits enrich everyone, focuses on the core socio-economic unit in te ao Māori. Contrary to contemporary understanding, iwi weren’t the primary entity by which pre-colonial Māori organised themselves; in fact, whānau were. Expressed through whakapapa, whānau trace their ancestry back to the atua, and through them to the rest of the natural world. But whānau has come to reflect more modern kaupapa, for instance, shareholdings, friendships and the “virtual” family bridging geographical separation in cyberspace.

Associate professor Jason Mika (Tūhoe, Ngāti Awa, Whakatōhea, Ngāti Kahungunu), an expert in Māori business and indigenous entrepreneurship, explains that whānau are “self-sustaining, independent, interdependent units working to fulfil their needs.” Every whānau operates within wider networks – some are gathered into hapū, others are bound together by a common purpose. Regardless, they are best placed to distribute surpluses, defend against threats, realise opportunities and resolve disputes or re-form new whānau elsewhere. In the pursuit of improved wellbeing, whānau can build economic, social, cultural and environmental wealth. Thus, the Māori wellbeing economy.

As Rout outlines, it will need to be an economy built across a network of whānau nodes, operating according to traditional principles that have been recalibrated to the contemporary context and regulated by the flows of mana and mauri, with carefully constructed interfaces with the wider national and international economies and quadruple bottom line accountability. As well as insights from te ao Māori, the Ngā Pae researchers will also draw on the broader international wellbeing economies movement, which shows strong convergence with te ao Māori across a number of themes.

As it stands, Māori earn their living not in the taniwha economy, but within the New Zealand economy. The wider general economy perpetuates an unequal distribution of income and wealth for all – but especially for Māori. The net worth of Pākehā households remains significantly higher than that of Māori, with the gap widening in the older age cohorts. While the Māori unemployment rate has broadly fallen in the last decade, it’s nearly double the Pākehā rate of 3%. A lack of formal education is one reason for the disparity, as are lower rates of self-employed Māori and Māori employers – two forms of employment where capital lies in Māori hands. Overall, the knowledge, skills and abilities (or human capital) of tangata whenua is likely less valued than Pākehā human capital in the Aotearoa workforce.

Human capital is important because societies with higher-skilled workforces are likely to be prosperous. It’s a complex space for Māori, partly because tangata whenua often assume additional work teaching and upskilling Pākehā and other New Zealanders in te ao Māori. Intuitively, Māori are attracted to this cultural “double duty” for it engenders cultural respect, says Professor Jarrod Haar (Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Mahuta), an expert in human capital. But serving as guides is a potential “sneaky” trap because the cultural burden is typically not recognised through extra remuneration or promotion. Organisations and businesses seemingly have an appetite to do well by Māori employees. “It’s just striking that balance,” Haar says.

Is the Crown necessary?

The taniwha economy has made good within the indigenous and colonial scaffolding of Aotearoa New Zealand. But the benefits of its multibillion-dollar asset base aren’t immediately helping alleviate existing disparities. Can Māori reimagine the taniwha economy by themselves? Yes and no, Mika says. Māori aspire for mana motuhake but the Crown must still enable Māori to “have that potential to be economically self-sufficient within themselves”. Indigenous economist Dr John Reid (Ngāti Pikiao, Tainui) adds present and future governments can do so much more for Māori in fulfilment of their treaty obligations. At the same time, iwi are already contemplating a system to regulate economic activity, and possibly generate tax revenue, within their exclusive rohe – independent of local and central government. Synergy is possible between the treaty signatories, Reid says. “At the same time, the Crown’s got a huge role to play.”

An aspirational and real future awaits whānau, Spiller says. A future where they take control of their own lives and help other whānau do so. A future where tangata whenua continue performing their primordial duty to care for a world they are innately a part of. And a future where Māori achieve multidimensional wellbeing, in the face of upheaval and in the pursuit of self-determination. A taniwha with teeth of silver and gold is on its way, we hear. We shouldn’t fear the creature’s shining niho. We shouldn’t worship them either.

Click here to read the full report by Dr Chellie Spiller et al: Te Niho o te Taniwha: Exploring present-future pathways for whānau and hapū in Māori economies of wellbeing.