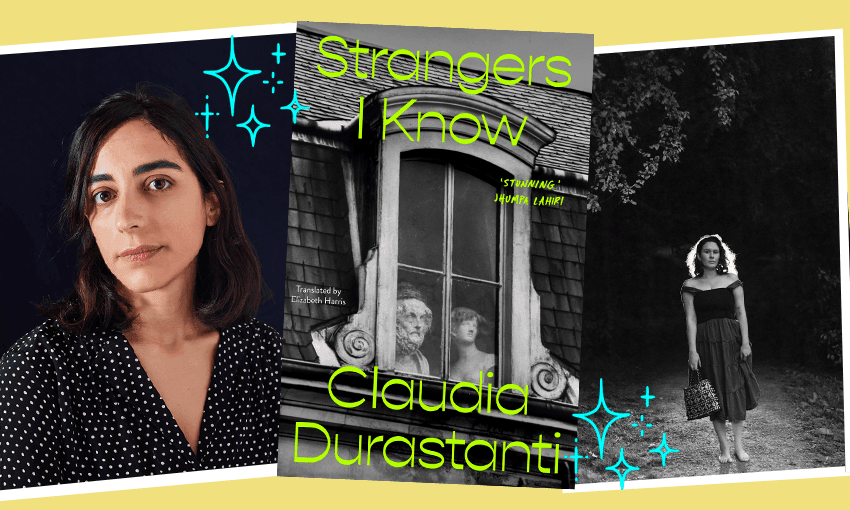

Michelle Rahurahu reflects on Claudia Durastanti’s award-winning work of auto-fiction/memoir, and how the daughter’s life in the book intertwines with her own.

I spoke to fellow CODA (Child of Deaf Adult) and author of auto-fiction Strangers I Know Claudia Durastanti recently, and we agreed the Deaf world is anything but quiet. It’s full of noise, it’s musical, it’s emotive, it’s slamming pots and pans in the early mornings, it’s punk rock. We Hearing people can be so ignorant to the other senses involved with noise; doesn’t it feel good to slam a stick on a drum? Doesn’t it feel good to scream?

Claudia and I differ in our identities; I took on the classic archetype of the CODA, a precocious bilingual child that acts as the in-house interpreter, attending doctors meetings, bank meetings, school meetings, counselling sessions, anything that was too last-minute for an actual paid interpreter. I was there, playing the mouth of my parent, while my Maamaa would stand by my side, slapping my arm, asking, “what did they say?”

“…What?

How will my brain

know what to hold

if it has too many arms?…”

– Echo, Raymond Antrobus

The daughter in Strangers I Know, a shimmer of Claudia herself, diverges from my experience. Her parents didn’t teach her or her brother, for various reasons, but there is still resonance. Like in Strangers, my Maamaa took the main caregiving role, while my father was estranged and volatile. In Strangers, the parents are fearless, almost flagrant about how different they were, “[the father] realised he’d been searching his whole life for someone like himself. Someone not interested in facing disability with bravery or dignity, but with recklessness and oblivion”. My Maamaa was the same. She has never flinched at the opportunity to be heard. The difference is the parents in Strangers desire to be on the outside, they embraced their position as aliens. My Deaf parents desired to be on the inside, and in many ways, I was the bridge to that world.

If you are unfamiliar with CODA as a subculture, I imagine you might feel they are hard done by. I’ve had teachers, parents of friends, and strangers all consider me with some degree of pity; “Oh that must have been hard” … “That’s such a big burden for a child”. Very rarely was there any recognition of how lonesome my Maamaa’s life was inside a Hearing world. Without a signer receiving her voice directly, she would sit to the side like an appliance without a power source.

“…What is it like to be curious,

To thirst for knowledge you can call your own,

With an inner desire that’s set on fire —

And you ask a brother, sister, or friend

Who looks in answer and says, “Never Mind”?

You have to be deaf to understand…”

– You Have To Be Deaf To Understand The Deaf, Willard Madsen

To be a CODA is to be praised for things your parent does while spinning plates. I was praised for being bilingual even though my Maamaa is bilingual as well. I was praised for my communication skills, when my Maamaa’s communication skills were better from a lifetime of talking to people that didn’t speak her language. Perhaps that was something the parents in Strangers understood before we did; there are no medals awarded for conforming.

A teacher, trying to embrace my culture, assigned a day for me where I could sign everything I said but no one else could sign, and so, I was talking to myself the whole day. In those moments, I was getting a taste of how isolating it could be to be so close to the world, and not be able to join it. I was also learning that I was community-made: that everything I had learned resided in the mauri of the people that raised me, and to fish that knowledge out of that stream to peer in on it, would only inspire a deep whakamaa as I watched it flap and gasp on the surface.

“…God,

deaf have something to tell

that not even they can hear —

you will find me, God,

like a dumb pigeon’s beak I am

pecking

every way at astonishment….”

– A Cigarette, Ilya Kaminsky

In Strangers, the daughter’s life is fractured through travel, poverty, whaanau fallout, absenteeism. Mine on the other hand was hardening, becoming rigid. Adults would take me aside and speak privately with me about my Maamaa as if she was an unruly teenager. Often, I was treated like the true adult who could decide how and when news was delivered to her, whether that was a diagnosis, a test result, a personal grievance. And so I marched through our house like a tightly-wound financial broker, considering every curve of my hand, weighing the pros and cons of a gentle approach versus a pragmatic one.

And then, I would overhear family friends saying vile things about her to everyone in the room but her. I would hear WINZ officers calling her slurs under their breath. Teachers, future employers, bosses, strangers, friends, everyone had a fucking comment to pass and those comments sat in my hands. And they were directed at me, like we were both in on some joke; descriptors rang together, “Oh your Mum is so…” – “aggressive”, “loud”, “stupid”, “slow”, “violent”, “stingy”, “crazy”.

I’ve seen her lose living arrangements, opportunities and jobs to these adjectives. Similar adjectives are thrown around in Strangers, “…they called her ‘the mute’ or said she was a ‘the poor thing’ and God should have paid closer attention.” Cruel remarks are part of the territory, and perhaps my Maamaa had seen it all, but here comes the ethical dilemma; when my Maamaa asked “what did they say?”, what would be my answer?

Should her daughter have voiced all the terrible things they said, about the way she moves, the way she talks, their limited views of her abilities? Or should I shield her from them? I was a kid, and kids’ priorities are centred on themselves. I didn’t want my Maamaa to be mad. I didn’t want my Maamaa to cause a scene. I didn’t want my Maamaa to drag me back into a room where she would force me to voice her retaliation. I told her next to nothing, and I robbed her of an opportunity to stand up for herself. I did want to protect her as well, but mostly, I didn’t want to listen anymore.

“…I’m-sorry-I’m-sorry-I’m-so-sorry-I’m-hard-for-the-hearing

Repeat.

Repeat.

Hello, my name is Sorry

To full rooms of strangers

I’m hard to hear

I vomit apologies everywhere

They fly on bat wings

towards whatever sound beckons

I’m sorry. I’m sorry. I am so, so sorry

and repeating

and not hearing…”

– Disclosure, Camisha L. Jones

On days where I wasn’t available to interpret, my Maamaa would sit dejected at the living room table when I got home from school, eyes red. One time, she had walked all the way into the city with an empty suitcase to hopefully fill with a food parcel. When she was denied it, she screamed, and was escorted out of the building. I don’t even like to picture what that was like, what was said. But I became more comfortable stepping in to mediate, to voice my Maamaa – to anyone who threatened our family – with a cooler, placating tone.

I learned later in life that professional interpreters have an ethical code for these situations. They must communicate everything that is said in the room. No matter how profane, no matter how the individual feels about the content. They are not there to mediate or manage, they are there to communicate what is being said. The point is that everyone has a right to speak their mind, and the Deaf community are capable of making their own decisions about how to proceed. If my Maamaa wanted to fight, she should have had the authority to fight. It seems kinda obvious on paper, but the able-bodied community has a problem with the infantilisation of Deaf and Disabled people. I understand that a child cannot navigate these waters very well by themselves, but by playing the more reasonable version of my Maamaa, I confirmed what everyone in the room was thinking. That my voice, as a Hearing person, was naturally, better. And now as a writer, I feel that strain twice over, as the star of my own life, while the brightest in my whaanau shine behind me.

“…You and I,

can we see aye to aye?

or must your I, and I

lock horns and struggle till we die?

Your mind’s

not mine,

and your experience, I

experience – not –

can never learn.

Reverse, the same:

my life transferred’s

a blank…”

– Total Communication, Dorothy Miles

Strangers touches on the frustration with subtitles or captioning, how artless the craft is, how Dadaist it looks sitting lifelessly on the screen. “There were never subtitles for instrumental sections. No attempt, no effort whatsoever to describe what was going on in the rhythm, if it was slow or rapid, or dreamy.”

I feel that way about interpreting at times. I will watch my Maamaa artfully convey musical details of a story, play every character with gusto and contrasting tone, and then hear all the textures flattened out. There’s a reason, the language is so compact that to interpret it quickly would mean taking twice as long to speak.

Good translation takes time. Good translation is transformative. It’s a luxury our Deaf services don’t have. The most ideal situation is that everyone can Sign, or at least take time to build those skills, so that Deaf don’t have to hide in the fringes of society, waiting for a CODA or an interpreter. We try our best to aid but we can’t be all-seeing, all-knowing. And a life that is constantly negotiated through a third-party is without intimacy. If you want to understand the beauty and richness of Deaf life, you have to understand it for yourself.

Strangers I Know by Claudia Durastanti (Text Publishing, $39) can be ordered from Unity Books Auckland and Wellington. You can view Michelle Rahurahu and Claudia Durastanti in conversation online as part of the Rūbarū digital series by Verb Wellington.