Authors of feminist dystopia in the mould of Creamerie and The Handmaid’s Tale owe a debt to Herland, published more than 100 years ago, writes Donna Mazza of Edith Cowan University.

Recent television series Creamerie, a dark comedy from New Zealand where a pandemic quickly kills (almost) all men and male animals, revives the concept of an all-female society with a contemporary take on ideas raised by Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1860-1935) over 100 years ago.

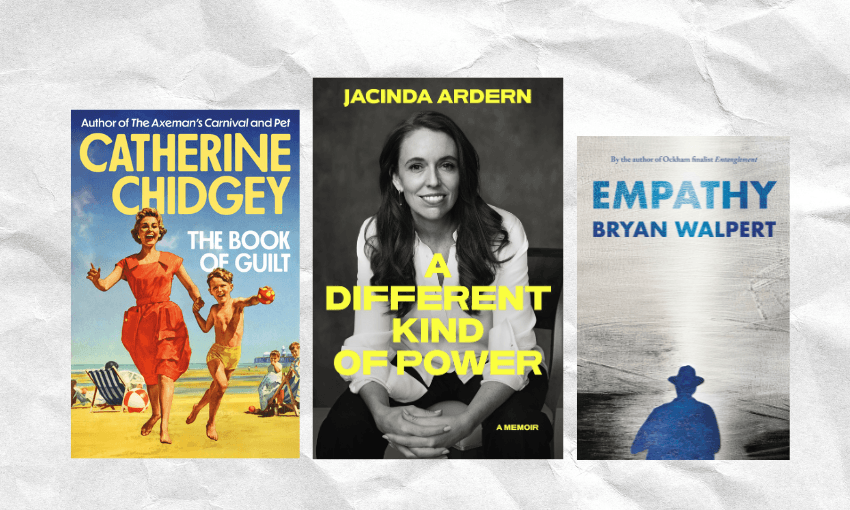

Perkins Gilman’s Herland (1915) is the kind of novel mentioned by critics who dive into speculative fiction dealing with gender or utopia, but it rarely gets serious consideration as a literary work in its own right.

Authors of feminist dystopia in the mould of Creamerie and The Handmaid’s Tale do owe a debt to Herland, but the work itself was out of print for 60 years and is a scarce gem in libraries and bookstores alike.

Perkins Gilman was an influential suffragette in America, and Herland was originally published as a serial in 1915 in The Forerunner, a monthly journal edited and written entirely by her for seven years. This is an extraordinary output for a single writer in any circumstances or era.

The book was published as a full-length work for the first time in 1979 by London based The Women’s Press Ltd. If not for the foresight of the feminist publisher, it might well have languished for more decades.

The novel is narrated by Vandyck Jennings, a sociologist out to learn all he can, and one of three men – alongside wealthy American Terry O. Nicholson who bankrolls the trip and Jeff Margrave, a smarmy doctor – who are on an adventure holiday into the wilderness of a continent resembling South America.

When their guides tell them about Herland, an isolated country devoid of men, they are keen to go and try their luck with the women; Terry aims to be “king of Ladyland”.

A land without men

Soon after their first journey, the men return so they are not beaten to “the good lookers” in “the bunch” by some other fellows. They take a small aircraft to map the forest, landing on a wide rock “quite out of sight of the interior”.

“They won’t find this in a hurry,” says Terry, even though the women had run out of their houses and watched them fly over: this is one of many subtle digs by the author foreshadowing the way the men underestimate the intelligence of the women.

The men scamper through the landscape, armed and dangerous, fuelled by the promise of lusty adventures and thoughts of fending off the men they know must be hidden somewhere, as they have seen babies and children on their flyover.

But there are no men. The explanation for 2,000 years of ongoing procreation comes a third of the way through the novel, where a chapter is dedicated to the history.

After escaping slavery in a harem and having “no-one left on this beautiful high garden land but a bunch of hysterical girls and some older slave women” there followed a decade of working together,

growing stronger and wiser and more and more mutually attached, and then a miracle happened — one of these young women bore a child. Of course they all thought there must be a man somewhere, but none was found. Then they decided it must be a direct gift from the gods, and placed the proud mother in the Temple of Maaia — their Goddess of Motherhood — under strict watch. And there, as years passed, this wonder-woman bore child after child, five of them — all girls.

The three men are captured and held in a “fortress” for six months under the watchful eye of older women they disparagingly dub “Colonels” — and kept well away from their trousers and any young women.

Clothed in the same tunic as all Herland residents, they learn the language and are quizzed about the lives of women in their own country. Here, they divulge “the poorest of all the women were driven into the labour market by necessity” and two-thirds are “loved, honoured, kept in the home to care for the children” but it is a “law of nature” the poorest have the most children.

The men “escape” under subtle observation and soon form bonds with the three young women they met up a tree on their arrival: Alima, Celis and Ellador.

By the end of the novel, Jeff is “thoroughly Herlandized” and all set to live with Celis in this utopia. The narrator, Van, marries Ellador and his social observations lead to some shifts in thinking (their story is the subject of the 1916 sequel, With Her in Ourland).

Wealthy misogynist Terry is intractable in his patriarchal attitudes. He is abusive to Alima, put on trial and expelled from Herland.

The Amazons

The 12 chapters of Herland are structured around topics (“A unique history”, “The girls of Herland”, “Their religions and our marriages”) that might easily be the titles of an anthropological work from the period.

The tone of the writing mimics an authoritative patriarchal voice. This is obviously intended to be ironic. The novel is darkly comic and filled with subtle digs at the male characters and the inequality faced by women in 1915, especially in response to work and economic disadvantage.

The concept of a female-led society in the west has its roots in Ancient Greece, in the work of Homer who captured stories of Amazon warrior-women in Iliad. Amazon women like the fearsome Penthesilea, who battled Trojan warriors, feature in a range of Greek tales, where they are usually depicted as succumbing to the swords or charms of male protagonists like Achilles and Theseus.

The Amazons have been reimagined by authors in many contexts since, featuring in art, literature — and Wonder Woman.

-

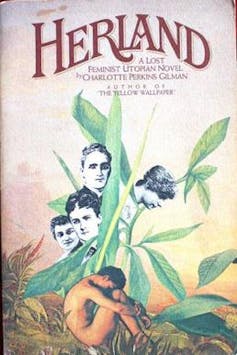

Ruth Hollick collection. State Library of Victoria

Herland pays homage to them, too. The legendary Amazons of Greek myth inhabited a remote homeland at the edge of the “world”; Herland seems to be located in an area resembling the Amazon.

Considering the geography of Herland is a well-forested triangle, the witty Perkins Gilman might also have been intending a symbolic connection with female anatomy.

The Yellow Wallpaper

In her time, Perkins Gilman’s ideas about the public role of women, prevalent male attitudes to women and the structure of the family were radically feminist.

This wasn’t the first work of hers which took up such ideas.

She is best known as author of The Yellow Wallpaper (1892), a short story narrated by a woman locked in an upstairs nursery by her husband — who is also her doctor — to treat a nervous condition with the “rest cure”. The rest cure was commonly prescribed to treat what we now call postpartum depression, which Perkins Gilman suffered for three years. It involved restriction of all activity, including reading and writing, while being confined to bed.

Deeply disturbing and gripping, The Yellow Wallpaper is an exposé on the treatment of women by medical professionals and narrates the woman’s descent into madness in disturbing detail. Perkins Gilman’s own physician, Silas Weir Mitchell, read the story and, as she claimed, discarded the rest cure in response.

The Yellow Wallpaper predates Herland by a couple of decades, but in comparison, the writing in it is more loose and dynamic. Perhaps the first-person male protagonist in Herland was a less comfortable narrative position for the author, with her well entrenched feminist ideals. The writing in Herland is not as rich in motif and layers of meaning. Characterisation of the women in the novel lacks depth, but this may also be ironic.

Overwhelmingly, the purpose of this feminist classic is to critique the social and economic system that restricted American (and other) women through limiting education, financial independence and life choices. As a novel, it reads as ideology-driven and a vehicle for women’s rights — but it is also very funny. Its ironies are still potent, and sadly valid.![]()

Donna Mazza is a senior lecturer in Creative Arts at Edith Cowan University in Western Australia. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.