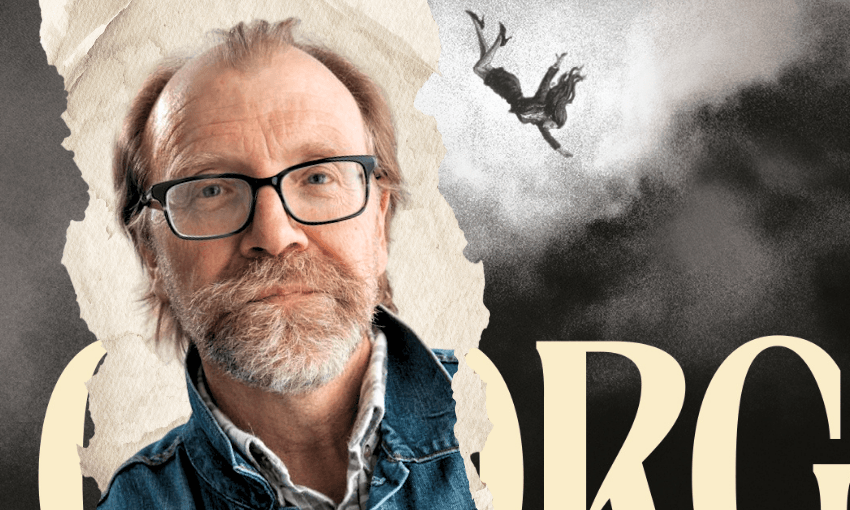

Bernard Beckett is a brainy, elegant writer, best known for his young adult novels Genesis, August and Lullaby. Here, with a new book in the offing, he shares his rule for stacking up stories that work.

Like most who dabble in writing, I’ve tried my hand at a few different formats: play scripts, screenplays, novels for teens, one for adults and now my first middle-reader, which means it’s aimed at readers in those end of primary years, or thereabouts. While each format has its own unique demands, there are commonalities too. Prime amongst them is surely the need to construct an effective narrative.

I have a rule of sorts when it comes to narrative. I’ve found that if I don’t know the ending of the story before I start writing, I’m much less likely to develop a coherent narrative. The reason is fairly obvious: a compelling narrative always feels in hindsight like a slow playing out of its endpoint. Whoever it was who said “the best endings feel both surprising and inevitable” hit the nail on the head. The surprise component is the thing that makes the story worth telling in the first place, not necessarily the Sixth Sense smack-you-in-the-face surprise, but the satisfying falling into place of the last stepping stone that allows you access to the shore, that you may turn back and regard the journey. And the inevitability comes from the way every element of the preceding story feels as if it is indeed a step to exactly this destination.

It may well be that many writers have a sixth sense of their own that guides them towards the surprising and inevitable ending without knowing it in advance, and I envy them that talent. It allows the writing process to remain fresh and full of possibility. Often enough, I’ve been bewitched by the promise of an excellent ending just around the next bend, but for now they’ve been nothing but mirages, and I can point to an awkward number of not-quite-good-enough novels in my past to make the point. [Ed: Beckett has a peculiar but appealing habit of publicly ripping apart his own novels; click on each book on his blog to read his takes.]

When we teach improv in drama classes, we often use the “because game” which gets our budding storytellers to make each new event, no matter how banal, the result of the event that fell immediately before (because I slept through my alarm, I missed my bus … ). This gets to the heart of what an authentic narrative is, I think, one where the events it traverses seem to spring causally from the world that has been created. Kant and Hume may have had a point, and causation may be itself a kind of mirage, but it’s how we perceive story, from the very youngest age. Anyone who’s sat beside a pre-schooler during a kids’ movie will be familiar with the “why did they … ?” questions. So not only is the writer trying to shepherd their story towards the ending that justifies the telling, but they’re also trying to get there without any of the sudden and perplexing shifts in circumstance, character or motivation that threaten to shatter the magic viewing glass.

The most telling fail, for me, is not the deus ex machina moment, which mostly you have the self-respect to avoid, but the betrayal of a character you’ve spent the last 200 pages carefully developing. You realise belatedly where you need the plot to go, and the only way to get it there is to have a character do something you know in your heart they’d never really do. I think most of us are vaguely aware we’re doing this, but there’s a special sort of hope-tinged denial that, twinned with a deadline and crashing exhaustion, pulls you irresistibly toward mediocrity.

Speaking of twins, I probably should at this point mention the new novel, The Tunnel of Dreams. It’s the tale of a pair of identical twins who find their way into an alternative world, where it becomes their job to help a newfound friend rescue a prisoner from a cage. Things get quickly complicated, as they will. It was written initially as a story to read to my boys. I would cobble together a small section each day and then read it to them as their bedtime story. They would pass judgement and suggest improvements. Given they’re also twins, you might assume there’s some correlation between the fiction and its audience, but on that matter they will not let me comment.

I knew the ending of this one early, which would normally be reassuring. However, my editor was keen to change it. She’s an astute and formidable reader and perhaps I was foolhardy to resist the suggestion. Perhaps I just couldn’t stomach the thought of having to start again.

The Tunnel of Dreams, by Bernard Beckett (Text Publishing, $21) will be available at Unity Books Wellington and Auckland as soon as a shipping logjam clears. For now you can preorder, or buy it as an ebook.