Never heard of Acotar? Unsure what makes fairies sexy? Nervous of romantasy? Bemused by the term Medievalcore? Herewith is all you need to know about the hottest publishing trend of the age.

What is fairy smut?

Fairy smut is a genre of fantasy romance (romantasy) that includes both fairies and sex. If you pick up a novel and the blurb mentions anything to do with fairy courts, or fae lands, or faeries (or fairies) and fiery passion, then you’ve probably picked up some fairy smut.

Why are we talking about fairy smut?

Because it’s astonishingly popular. Unless you’ve been kept captive in the otherworld you’ll have heard of the term romantasy, and highly likely in the same sentence as the name Sarah J. Maas. Maas is one of the world’s best selling authors. In 2024 her publisher, Bloomsbury, recorded its highest sales year ever, largely down to Maas’s A Crown of Thorns and Roses series (Acotar as the fans call it) seeing a 161% increase in sales. Acotar is the book that launched romantasy – and the sub-genre of fairy smut – into the culture. In Maas’s fairy-dust-laced wake came blockbuster romantasies like Rebecca Yarros’s Empyrean series; the latest of which, Onyx Storm, became the fastest selling adult novel in 20 years when it was released in January this year. While Onyx Storm doesn’t have fairies as such, it does feature some compelling dragons (and leather, and sex. Let’s call it dragon smut.).

What is Acotar actually about then?

“Feyre is a huntress. And when she sees a deer in the forest being pursued by a wolf, she kills the predator and takes its prey to feed her family. But the wolf was not what it seemed, and Feyre cannot predict the high price she will have to pay for its death…” So reads the blurb for the first in the Acotar series, A Crown of Thorns and Roses. It’s a beloved book, and Feyre a beloved character. Her story is compulsive, the world beautiful and the folk horny.

In fact, many fans of Acotar whole heartedly reject the term “fairy smut” as a derogatory term for a genre that women, in particular, love. They see the term as a way to undermine entertainment that appeals predominantly to women and that celebrates women enjoying sex.

Aotearoa book buyer at Unity Books, Melissa Oliver, says she’s sick of backlash against romantasy and it’s thanks to Sarah J. Maas that she was introduced to the fantasy genre at large: “I wouldn’t have read fantasy if I hadn’t have read her books.” Oliver says that one of the defining features of romantasy is that while you have the cornerstones of fantasy in great world-building and exciting plots, in romantasy “character is also so important.” Oliver says while the plots are thrilling there’s a lot of character-driver storytelling at the heart of it. This gives some clue as to why so many people around the world have connected to Acotar in particular: they can relate to a central, strong female character and get an anchor-hold in the epic multi-book story through what happens to her along the way.

Where does romantasy come from?

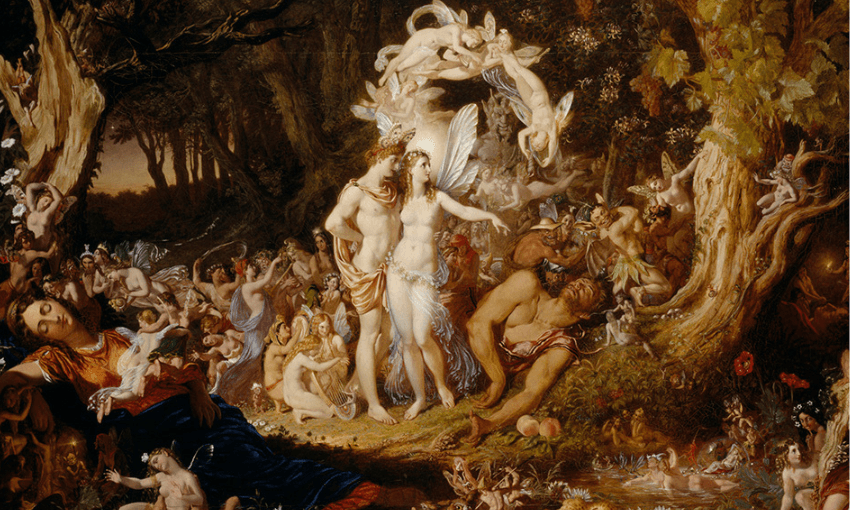

Sexy stories are as old as we are. Fairy stories, too. Fairy literature, however, flourished in the Middle Ages when stories of the otherworld shifted from oral storytelling traditions and into literary forms; and it flourished again in the Victorian period when fairy paintings became popular. Romantasy as we know it today draws upon centuries of storytelling about humans crossing into otherworlds, or those otherworldly beings crossing into ours, which is a foundation of the fantasy genre at large.

In the story of Sir Orfeo – dated to the late 13th Century – Orpheus must rescue his wife Heurodis from the fairy king who stole her from beneath a tree (likely apple, or cherry… sexy fruit) where she’d been napping. It was hugely influential retelling of the classical Orpheus myth but shifting the underworld to the otherworld and drawing in myth and legend of the fae which is deeply rooted in Celtic and British folklore.

Sarah J. Maas has cited the 16th century Scottish tale, The Ballad of Tam Lin, as one of the inspirations for Acotar. Tam Lin hinges on the giving and taking of virginity and stars Janet (sometimes, Margaret – there are many versions of the legend given it was an oral tale to start with), who must travel to the otherworld to rescue Tam Lin, her true love, from the ferocious, fascinating Fairy Queen who is holding him captive in her court.

Once you start trying to locate the influence of fairy stories you can see them spiking popular culture across almost every decade from the Middle Ages on. Take the British writer Sylvia Townsend Warner’s 1977 collection of short stories, Kingdoms of Elfin, which is a startling series of tales about the hi-jinks in various fairy courts (one of which is called Elfhame, the Scottish Elf-home), their desirous natures, their militant societies, and sometimes, their cruelty. Wildly brilliant children’s writer Diana Wynne Jones wrote her own version of Tam Lin with her young adult novel Fire and Hemlock (1984).

New Zealand’s own Nalini Singh has been writing romantasy for years – not strictly involving fairies but there are some, and there plenty of changelings who seem fairy-adjacent. Elizabeth Knox had a huge hit in 2019 with her fantasy novel, The Absolute Book, which features the Sidhe, or the fairy realm.

Cult 80s film The Labyrinth starred Jennifer Connolly as Sarah – who, when you look from the lens of 2025, was clearly Medievalcore (those puffy sleeves, long hair, penchant for olde worlde books about goblins) and reads now as a surefire fan of Acotar. The Labyrinth follows the classic structure of young mortal having to cross into the otherworld to save a loved one (her baby brother Toby in this case) from a dastardly fairy Regent (Jareth, the Goblin King, played by David Bowie – a look, a personality etched onto every millennial’s mind in confusing ways).

The artist who created the goblins of The Labyrinth, Brian Froud, is a world renowned fairy artist and expert in fairy related folklore – his work also spawning acres of fan art, live events, parasocial interconnectivity and conversation about the ongoing role of fairies in our lives.

But why is fairy romance popular right now?

In an article published in the Guardian just this week, sex therapist Vanessa Marin says that so many of her clients were reading the Acotar books that she had to dive in too, to understand the appeal and the effect they were having. What she found was that the books were reigniting desire and reinstating sex as a joyous and fun experience, particularly for women who had thought they’d lost their libido.

It’s similar to the Bridgerton phenomenon which draws on the Regency period and the worlds of Jane Austen and pals to create a sexy fantasy version that will inevitably end up with fingering in a carriage.

There’s also the escapism: romantasy novels, when done well, are easy to slip into. They’re fast, evocative and loaded with magic. The popularity of romantasy has affirmed that magical worlds don’t only appeal to kids – other worlds are the stuff of possibility, of high stakes, and can ignite the imagination.

The pleasurable side effect of holding such imagined worlds inside your own brain is that it can rub off on the real one. Romantasy fan communities flourish online and in person: Acotar has spawned a thousand meetups, whether through book launches, author conversations, Acotar festivals, Actotar themed events, and good old online chat forums via the likes of BookTok. Romantasy enables parasocial relationships, like-minded communion – real-world extensions of the literature itself.

Romantasy, in short, can improve your quality of life.

What has all this got to do with Medievalcore and what is Medievalcore?

Medieval motifs are central to romantasy, particularly the novels that involve fairies, dragons, your standard fantasy creatures which derive from Medieval literature, art and folklore. Romantasies like Acotar, and like Rebecca Yarros’s series, have contributed to what definitely looks like a revival of interest in both Medieval history and a Medieval-esque aesthetic (or often really a Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic – an art movement that blew up in the 19th Century and that drew on Medieval and Renaissance stories and aesthetics) that can be seen in the explosion of bloomers for sale, in Chappell Roan’s silky corseted gowns, velvets, long red tresses and swords.

Unity’s Melissa Oliver, says that she feels the Medievalcore trend in her bones. She’s noted that we’ve moved on from the boom in Ancient and Classical retellings and have shifted into what just might be a boom of Medieval retellings like For They Great Pain Have Mercy On My Little Pain by Victoria McKenzie which imagines the lives of famous Medieval women Margery Kempe and Julian of Norwich. Or like Lauren Groff’s novel Matrix which imagined in thrilling detail (and not a small amount of sex) the life of Medieval Abbess Marie de France (Groff drew heavily on the life of famous Medieval nun, Hildegard von Bingen). Oliver can also see Medievalcore start to go off in the YA space with books like Quicksilver by Callie Hart which Oliver says is flying off the shelves.

The fashion world is predicting that Medievalcore is the trend of 2025 which begs the question of what came first? The books or Chappell Roan’s pointy Medieval-esque hat or the Weird Medieval Guys Twitter handle that bred its own spinoff book, and a thousand other social media accounts plucking out funny/weird images from Medieval manuscripts and amassing huge followings? The more you look the more you can see the influence of Medieval art and aesthetics creeping around the culture: the feature image to a BBC article on the 40 most exciting books to read in 2025 shows a very Medieval-y woman reading a book, her hair plaited and wound up on her head, a wide frill collar on her dress.

Should I try some fairy smut?

Oliver says she sometimes encounters customers who are ashamed of their craving for romantasies. “Don’t be!” she implores. “They’re fun, they’re fast, there’s great stuff about home and family and friends being important. Read it for the fun.”