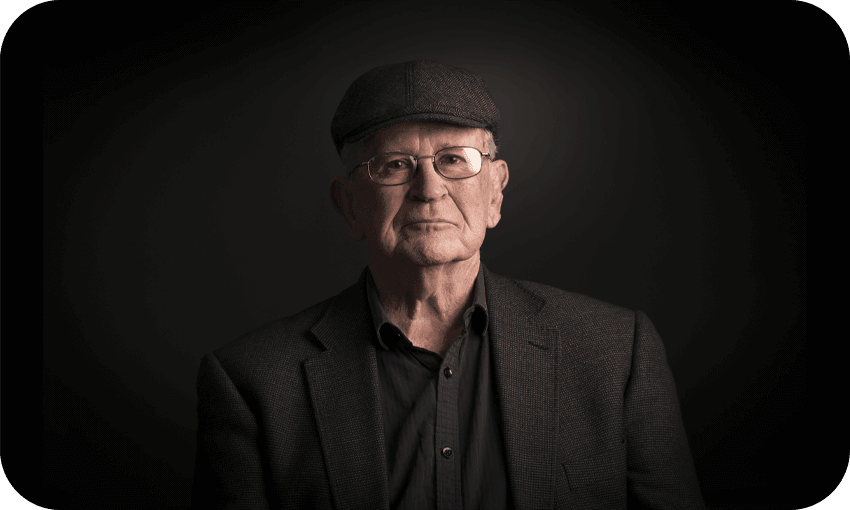

We remember one of Aotearoa’s towering literary figures, who died on Sunday 28 April.

Sir Vincent O’Sullivan, one of Aotearoa’s most prolific writers, has died in Dunedin at the age of 86. His son, Dominic O’Sullivan, shared the news on social media on Sunday 28 April:

“Hei aitua hoki, kua hinga toku matua,

“I am profoundly sad to share that my father, Emeritus Professor Sir Vincent O’Sullivan, died in Dunedin late yesterday. I was present with his wife Helen.

“In the next day or two, Vince will travel to the Home of Compassion in Island Bay, where he will repose ahead of his Requiem Mass later in the week at St Mary of the Angels, Wellington.

“Requiescat in Pace.”

O’Sullivan was born in Auckland in 1937, the youngest of six children, and went on to study at the University of Auckland and then at Oxford. His literary career was varied and brilliant and hugely productive, with lecturing stints, residencies and fellowships at Universities in New Zealand and Australia; and a long and beloved professorship at the University of Victoria in Wellington where he taught until he retired in 2004. His contributions to Aotearoa’s bookshelves, to students, to literary conversation and scholarship is so immense that it is difficult to summarise in any sensible way: he was a mind of extraordinary capacity.

Between and throughout his academic career O’Sullivan wrote and wrote with unwavering energy. His first book of poetry, The Burning Man, was published in 1965 and was the first of 21 collections; the latest – Still Is, a collection of 90 new poems – is due to be released by Te Herenga Waka University Press in June this year. O’Sullivan also published seven collections of short stories, three novels, nine plays and 10 librettos. He was the author of acclaimed biographies of John Mulgan and Ralph Hotere. He was the New Zealand poet laureate for 2013–2015. In 2000, he was made a Distinguished Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit, and in 2021 he was redesignated as a Knight Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit.

It was his work on the letters and stories of Katherine Mansfield that made O’Sullivan renowned in global academic circles. Between the 1980s and mid 2000s O’Sullivan co-edited five volumes of Mansfield’s collected letters, making her inner life accessible to scholars and fans all over the world. O’Sullivan also edited collections of Mansfield’s poetry and stories; as well as editing collections of New Zealand poetry and stories at large.

In 2017 O’Sullivan wrote this characteristically prismatic piece for The Spinoff in response to the then Wellington Mayor’s idea to repatriate the bones of Katherine Mansfield. In it, he writes: “It has always struck me as a curious thing, how readers at times so hanker to own an author, beyond carrying her books in a shoulder bag, or reading her in a library. That urge to get closer, to know what life was like when she wasn’t writing, to pick up scraps she didn’t know she had let drop. It is an understandable, even a touching, trait. Mansfield readers often seem more than usually prone to the condition. I have heard of “Kezia Parties” on October 14 where even men are permitted to wear pinnies. Or an event on May 3, when guests are invited to throw paint balls at another guest whose name is drawn at random to dress up as Middleton Murray.” A taste of the scholar’s generosity and delight in human nature.

I was always struck by O’Sullivan’s reviews. Examples I study both for their scholarship, and for their serious intentions: you can always see the mind at work. Take his thoughts on Lloyd Jones’ tricky novel, The Fish, which confused readers and critics. In his review on The Spinoff, O’Sullivan applies an informed close reading, an academic’s clear-eyed judgement, and a generosity towards the project of the searching writer. And who else but O’Sullivan to tackle the 700-page biography of Allen Curnow and make the analysis sing?

Close friend of O’Sullivan’s, and fellow writer, Dame Fiona Kidman says: “Vincent and I were among the founding Trustees of the Randell Cottage Writers Trust. He remained on the Board throughout its history, and in the latter years was its Co-Patron, a position he held until his death. Vincent O’Sullivan was a defining literary figure in the 1960’s and 1970’s. He was part of a group that seemed golden when I first knew him: Lauris Edmond, John Thomson, Alistair Campbell, Harry Orsman. Everyone seemed to know him and everyone had a witticism of his to savour and repeat. I was in awe of him. But the person I came to know was one of the most tender hearted and generous of men, who would drop everything for a friend, who would go in to bat for other writers, especially newer and less well-known ones finding their way. We talked nearly every week for decades. To say I will miss him does not even begin to cover it. And who now will I save the Wellington goss for?”

I did not know Vincent O’Sullivan well but on the occasions I did get to spend some time with him – mostly at writers festivals where he would always be in the prime spots, revered and looked up to as someone with dazzling knowledge and huge experience – I was struck by his forward momentum, his palpable vibrancy. He seemed to me as someone lit by intelligence and curiosity; who had an internal creative drive that meant he was always producing something, working, thinking. It’s a trait shared by many great writers: a need to keep going, keep looking out and in at the same time. It seems very Vincent to have a huge collection of poetry coming out this year, now posthumously.

Thanks to the academic tradition of the festschrift (the term for a book created to honour an academic career) there is an anthology of writing that celebrates O’Sullivan’s varied creative lives called Still Shines When You Think of It, co-edited by poet Bill Manhire and academic Peter Whiteford, and published in 2007 to mark Vincent’s 70th birthday. A excerpt from introduction to the book goes:

“The cover design for Still Shines When You Think of It comes from another of Vincent’s friends, the artist Ralph Hotere. Their friendship goes back a long way. Ralph devised the cover for Vincent’s second book of poems, Revenants. Something went wrong back in 1973, however – perhaps the right inks and cover card were unavailable, perhaps the publisher couldn’t afford them. At any rate, Revenants was published with a sad grey cover, and thin orange rectangles contained the title and author’s name in severe black lettering. We are pleased that Ralph Hotere has given us permission to create something much nearer the cover he originally envisaged.

There is a further story about Revenants, a book Vincent no longer much cares for, which involves the offering of what are sometimes called financial inducements to students and friends to ‘liberate’ any copies they might find in libraries and bookshops. The story is probably too good to check, but we believe there is some truth in it. We hope Vincent will not want to organise the removal of this book from the public record, but if he wants to give it a go, we wish him the best of luck.”

In this insightful interview O’Sullivan’s student, writer Majella Cullinane asked Vincent about the theme of death in his poetry, wondering if it’s connected to Catholicism or a writer’s sensibility. O’Sullivan’s answer goes: “It seems to me pretty hard to imagine not being aware of what is inevitable, and twinned with birth, what no one can get away from. If death defines the kind of being we are, then how we think of it can be as diverse as there are individuals. If you’re not aware of death to some degree, then you’re pretending to be other than you are. Every story ends with it, if it is told long enough. But the story, for all that, need not be obsessed with it. Just don’t make out it’s not there.”

Tributes to Vincent O’Sullivan can be read here, and will be updated as more flow in.