Following his essay published yesterday, Duncan Greive talks to University of Otago professor Colin Gavaghan, an expert on regulating emerging technologies, about the challenges and opportunities of New Zealand taking on Facebook and Google.

Law professor Colin Gavaghan still carries with him a pronounced Scots accent, but during his decade in Dunedin has become one of his adopted country’s foremost experts on the regulation of what are called, somewhat euphemistically, emerging technologies. He started his career in medical law, but became fascinated by how the law grappled with sectors with potential and peril that wasn’t yet entirely known. He wrote his PhD on genetic technologies, before moving into broader technological fields like nanotechnology, information and communication technologies and artificial intelligence.

He seeks to help us understand how we should best grapple with the tension between allowing innovation while protecting society and institutions. “When’s the right time to do it? Where should our regulatory tape be, between precaution and progress?” He is currently director of the New Zealand Law Foundation centre for law and policy in emerging technologies, and sits on the Digital Council for Aotearoa, which advises the government on how to “maximise the societal benefit of digital and data-driven technologies”.

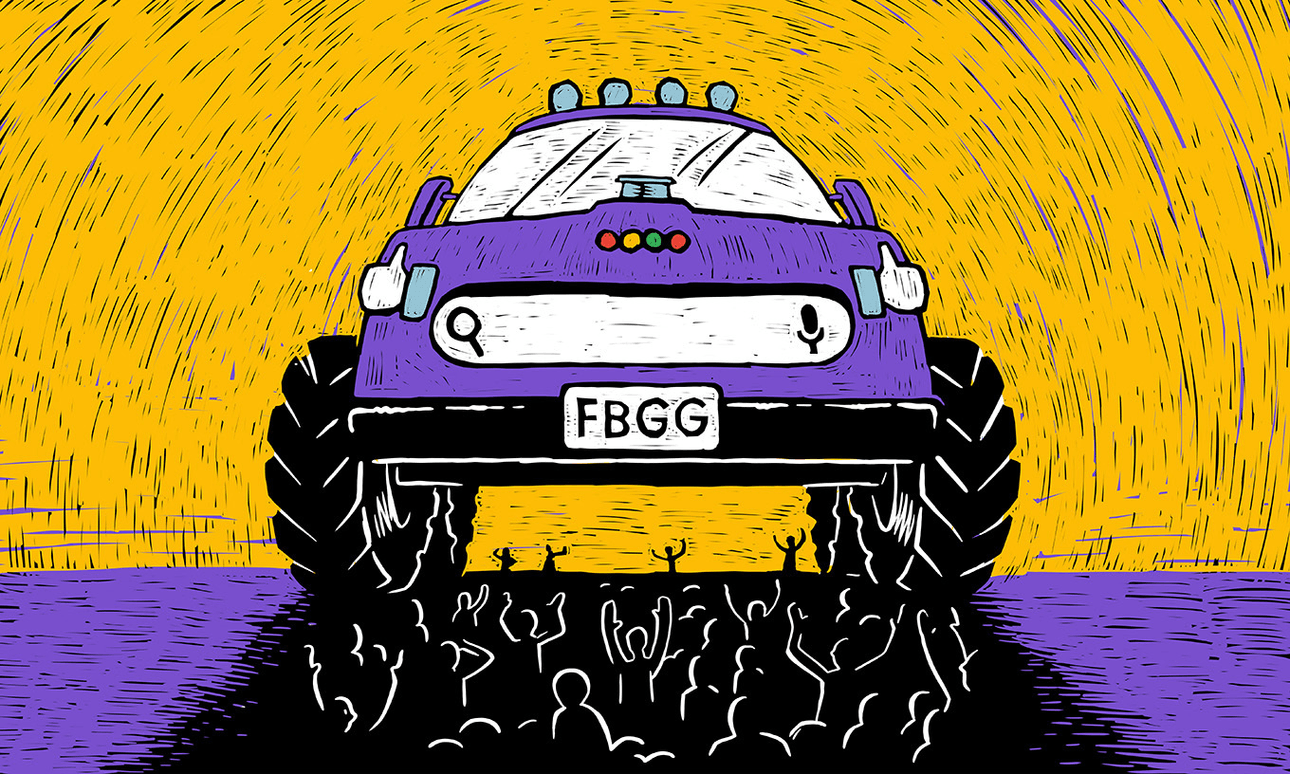

As a result, few are better placed to speak to the challenges and opportunities of technology regulation. Following my essay on the search and social giants published yesterday, I spoke to him about why The Spinoff is subject to far more regulatory oversight within New Zealand than Facebook or Google – and what the dangers are of simply leaving tax and regulation up to big countries that might not share our values, or operate under Te Tiriti.

The following conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity and brevity

Duncan Greive: Is there a ‘right’ time to regulate a new technology?

Colin Gavaghan: Tech lawyers like me talk about a thing called the regulatory phase. Which is the question of when is the right time to try and regulate a new technology? In some cases we’ve tried to get right out in front, we’ve tried to put rules in place before the technology even exists.

If you think of something like human cloning, you try and put a rule in place before it becomes possible. In other cases it’s much more wait and see. And there’s something to be said for both approaches, I think. Because, you don’t necessarily know enough to make good regulations before the technology’s being used. You don’t know where the problems are.

But if you think of your analogy with the car, I mean, it’s not like we weren’t aware of risks right at the start. At the very beginning, people famously would walk in front of the car with a red flag and it was at crawling pace. And then the automobile industry, they managed to redefine our built landscapes around the car. So you’ve got a little strip to either side of the road where people can walk and the rest of the space is dedicated to the car. Anybody who strays onto that space is a jaywalker.

I think with social media, they just managed to dominate the landscape before we even really realised what was happening and only belatedly did we just start to realise what we’d allowed to happen.

How would you characterise the current regulatory regime in New Zealand as it pertains to search and social media?

When you’re talking about emerging technologies; the fact that we don’t have a bespoke regulatory response doesn’t mean it exists in a regulatory vacuum. It can be subject to just the regular body of law. So for example, our defamation laws and our privacy laws can apply. So it’s not that there’s no law at all pertaining to these platforms, but there’s no specific law. There’s no handcrafted law to respond to those. And I think like the rest of the world, we’re struggling to deal with a new situation.

We’re now in a position where Google has more than 90% global dominance of the search engine market. Facebook has something like three billion users globally. We’ve never seen anything like this, in terms of global dominance by a very small number of players.

You’ve got WhatsApp and Instagram and YouTube – but they own those companies anyway. So it’s more or less two big players that are dominating the whole terrain. And only belatedly is our jurisdiction thinking about how to respond to that. New Zealand is, I would say in terms of regulation, looking to be a fast follower rather than a market leader.

I think there’s the sense that we don’t really have the muscle to hold these companies to account very much. [But] New Zealand did find itself propelled into the limelight a wee bit, following the Christchurch massacre and the Christchurch call. So we have, for some reason – probably not entirely justified – a very good reputation at the moment as being good guys in this space. And we’re getting invited to a lot of tables that we wouldn’t otherwise have been.

The enabling law that created user generated content and allows for a lot of what has grown in this space is section 230 in the US, exempting them from liability as publishers. Do we have a local equivalent?

No, we don’t really have anything to that effect. It’s one of the big areas of contention. I think that’s very much up for grabs. And I think there’s a sense here and in other places, it’s going to be tougher in the US. And I think what we’ve got to understand is that the US is sui generis about a lot of this stuff. Their approach to this issue and to free expression generally, sets them apart I think from a lot of the rest of the world. I think the claim from companies like the big providers to be just neutral conduits for other people’s content is becoming increasingly untenable.

As we find out more about their use of recommended algorithms and the choices they make… Certainly in Google’s case, following the right to be forgotten case, what they choose to deal and call together and not allow us to find in their search engine. They’re not just neutral carriers anymore, they’re making choices. And as it becomes more obvious that they’re making choices, then I think there’s a growing demand, that those choices be made more transparent and they’re more accountable. If you’re making choices about what we see, then you’re not a neutral carrier anymore.

That’s the thing that’s interesting to me, that they now employ tens of thousands of human moderators. The line on what they consider to be acceptable content is consistently in motion, just as it is with other publishers. And while you don’t want to be too cynical about this, they can afford to do more. Yet New Zealand still seems reluctant to take steps on its own, when the tech giants benefit from the idea that we need to figure this out as an international group. The longer that we do that, the more they amass war chests, build moats and become almost impregnable in terms of the way that they interact with society.

Is there a danger for New Zealand in essentially being hostage to a bigger international process, that the platforms themselves have an active interest in delaying as long as possible?

Absolutely there is. But that said, we also need to have a serious discussion about what it is we want them to do and where we want the regulatory burden to land. Because I think we’re still very excited about them. We like the fact that we have these free services available to us. We don’t like to think about how they’re being paid for, and that there has to be a model whereby they’re paid for. Would we be happy to pay an amount, an annual subscription, to use Google? Would that be preferable to what’s happening at the moment? For me, yeah, probably. But I don’t have a general sense of what New Zealanders feel about this, or if they’ve really engaged with it at all.

When we start demanding that they need to make regulatory decisions, I get a bit anxious. And the one that I keep coming back to is the right to be forgotten case in Europe. I’m quite okay with our judges and courts striking a balance between the public’s right to know and an individual’s right to privacy. Our law does that already. I don’t always agree with the exact line they draw. But on the whole, that’s an appropriate call for a judge to make. I’m not sure how I feel about some minimum wage content moderator for Google making that call for everybody else. I’m slightly uneasy about placing the regulatory burden onto Google without a supplementary burden that says, “and you have to invest in doing this properly.”

Here we have the likes of the broadcasting standards authority, the chief censor, an electricity regulatory authority, the commerce commission itself. We are used to having government agencies or quasi-governmental agencies that are perceived as – and mostly actually are – fully independent from the sectors that they oversee. Is there a case for building out some forum that isn’t actually within those companies, where these decisions can be made? And not waiting on the EU or the OECD to do that, but just trying it out.

There is. I think that there’s a regulatory tension here as well. I mean, I always seem to be complicating the suggestions people put forward and I see it as my role. But there’s a regulatory tension between wanting and needing quick responses, but also transparent processes that have proper due process. So if you think of it, something like the Christchurch shooter footage, speed was of the essence there. And it was tricky because it was a bit whack-a-mole for a while. because it was popping up in various iterations and the companies were trying to react to that and remove it.

In other cases, people want a proper explanation and there’s cases where the social media platforms have gone too far the other way. Famously, pictures of women breastfeeding have been taken down by Facebook. Because their algorithms can’t distinguish one kind of nudity from another. I don’t think it can be every single decision. I think some of the decisions can only be made by the companies because we need that speed, we need that fast reaction. And referring that to some sort of tribunal is going to take time. So for some cases, yes, they need to be the ones to do it.

One thing I would like to see is a review body that has an obligation to report what steps they’ve taken in certain regards. A requirement for transparency with regard to their recommendation algorithms, which could be reviewed maybe annually by a body to say, “Look, we’re not happy about how you’re doing this”.

Given the sheer volume of what passes through their various domains, this is inevitably going to be a big and costly body for us to fund as a nation. Is there a case for a direct digital services tax that in part, goes towards creating this regulatory regime?

Yep, absolutely. That would be an option. It’s an option that’d be seriously worth considering. I would also like to see a recognition of a need for professionalisation of content moderators. That it shouldn’t be something that’s delegated to this low level. And that’s partly because we’re recognising it’s a complex and important decision. But it’s also partly because there’s risks for the content moderators. And that’s becoming more apparent as well, constantly subjected to some of the nasty stuff on Facebook. Stuff that we don’t even get to see because it gets filtered out. There’s increasing reports that for some people, that’s taking a real toll.

So I think taking that aspect of it more seriously is a duty that could reasonably be placed on the companies; to pay and train these people properly for the importance of the decisions they’re making. How to tax them effectively is a whole other thing. But there’s a strong moral political case that can be made for making them pay for their own negative externalities, if you like. To actually say that if society’s going to have to pick up the harms from this, then you’re at least going to have to contribute to that cause. I would be supportive of that move as well.

Do you have a sense that any part of government – from MPs to the courts to the commerce commission – is taking a hard look at this?

No I haven’t, to be honest. I mean, there might be stuff going on behind the scenes, but I’m reasonably plugged in with government, I’m on the digital council and I think I would know if there was something major going on in this regard. So I don’t think there is.

I think we tend to be letting others do the running for us. So for example, the EU fined Google a whacking bit of money for anti-competitive practices a few years ago. Because of the search engine prioritising their subsidiary companies’ search rankings over the rivals. It’s abuse of that market dominance.

What are the consequences of that for us as a country?

The consequences of that is that we’re rule takers, not rule makers. That we end up having two things: one, that we get what other societies decided is right for them, that may not be right for us. And two, that perhaps we don’t even get that, because the possibility exists that these companies think, “well, New Zealand doesn’t have the clout to enforce these rules on us.”

We should have an input into these decisions. As you can tell from my accent, I’m a UK person originally. And it’s a little bit analogous to the UK’s position with regard to the EU now, that we’re going to have to more or less comply with EU law. But we don’t have any input into it. Should we be trying to introduce our own thinking in this regard? Ideally yes, I think we should.

I think about Te Tiriti o Waitangi. The undertakings that the Crown made there. Kaitiakitanga and other Māori concepts are embedded within that document. So by just saying, “We’ll just follow whatever the OECD or the EU does”– Te Tiriti is a fairly unique object which can’t be considered in a process like that.

I suppose it’s a bit analogous to buying off the shelf algorithms. The police trial of facial recognition technology last year, which just wasn’t trained on a population like ours. It couldn’t spot Māori and Pasifika faces because it was crafted for a different place. And I think that is the concern if we don’t have some input. It might turn out that the solutions proposed in Europe suit us just fine. But nobody’s even seriously asking whether that’s the case. And there could very well be unique aspects to our culture that have not been captured by that.