A scarred technology sceptic meets generative AI head on and finds it reassuringly – and usefully – boring.

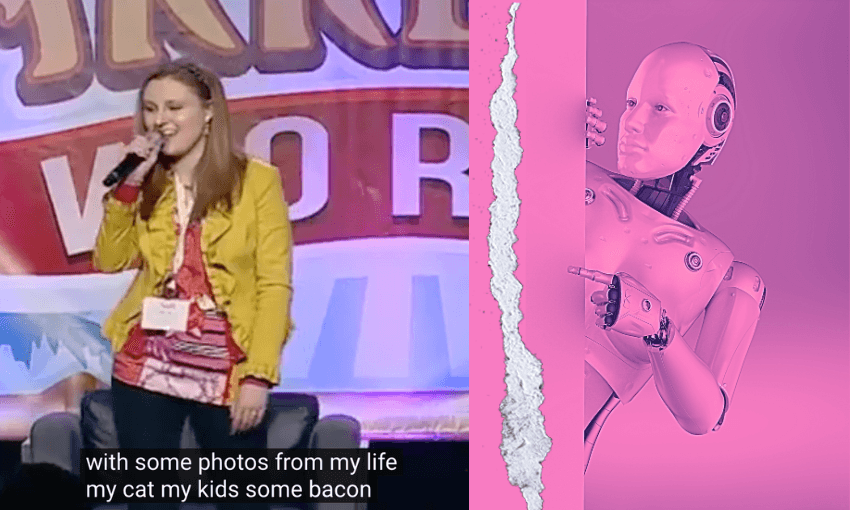

In 2014, Mary McCoy took to the stage at the Social Media Marketing World conference in San Diego and began singing a song that, for a brief moment, became a viral hit for all the wrong reasons. Dressed in a sunshine yellow jacket, McCoy stood in front of a backdrop that wouldn’t look out of place at the worst theme park you’ve ever been to, clapped her hands and unashamedly rhymed “engagement” with “bacon”.

Let’s get social, the song and the accompanying video, were rightly mocked online. If you were working in social media, as I was then, it was incumbent on you to perform your cringe about being part of the industry that allowed it to happen very loudly and very publicly. For me, it marked something of the nadir of my career; I realised that no matter how sensibly and boringly I advocated for sensible and boring use of social media in business, it was an industry where evangelists, gurus, rock stars, zealots and snake oil salesmen could, and would, get ahead. When upper management believed every brand, no matter how utilitarian, was just one good tweet away from Oreo’s 2013 “dunk in the dark” moment, insisting that we shouldn’t allow the social media tail to wag the business strategy dog was an exhausting way to earn a living.

I carry the psychic injury caused by Mary McCoy with me into most situations, but my scar tissue is especially itchy when it involves attending anything where I will be preached at by an American man standing at the peak of a technology hype cycle. I’ve been wined and dined at conferences in San Francisco and endured many presentations from many representatives of large technology companies interested only in selling more. I was possibly born a sceptic, but I maintain I have always been proven right about sitting through those presentations with one eyebrow raised and my arms crossed.

I took that expression and that posture into the first session of my AI for Business Mini-MBA back in May. The four-week course, established by Spark and offered to their business customers and other business leaders in Aotearoa, kicked off with a keynote presentation from Greg Shove, CEO of Section. Founded by Scott Galloway, Section is a business education platform and Spark’s collaborator in running the programme.

In person, Shove, wearing black with a big silver belt buckle shining at his waist, presents more as a kind of seasoned sheriff of the AI Wild West than a guru, evangelist or zealot. Section’s website promises business education for “real people” and not “rock stars”. Shove has founded five startups and sums up some of his career in tech as working at “the world’s hottest tech company when it was cold (Apple) and the coldest tech company when it was hot (all)”. While he is enthusiastic and knowledgeable about generative AI, describing it as “the opportunity of a generation” (he’s also the founder of a technical AI consultancy), ultimately, he struck me as a realist who has seen enough to sort the hype chaff from the practical wheat.

He offset my concerns about unbridled and uncritical enthusiasm about AI almost immediately by highlighting the obvious capitalism driving the “AI arms race”, plainly illustrating his statement that “big tech needs the next big thing” with a slide showing how revenue growth has fallen at Amazon, Microsoft and Apple over the last few years. I felt strangely reassured by his blunt assertion that big tech was all in on AI, governments were playing catch-up (again), and we, the people, were essentially lab rats.

Stepping through the course over four weeks, I oscillated between feeling like a lab rat, having regular existential freakouts, and realising that as foreign and apocalyptic as the generative AI revolution might seem, learning about its contextual use within business was awfully familiar.

The freakouts emerged after a couple of weeks of habitually using OpenAI’s ChatGPT4_o and Anthropic’s Claude as “thought partners”, “co-workers”, or “interns”, as we were advised to do during the course. I caught myself anthropomorphising these artificial neural networks, referring to Claude as “him” and “quite chatty and fun”, and I listened to and read too much about the philosophical and ethical concerns about AI. I lay awake at night, wondering what the point of being a writer was, and argued about whether we should fear or embrace AI. I now assume that this phase is what Shove meant when he pointed to the “wait, what?” dip in his slide about the AI learning curve.

At work, having only used these tools to ask dumb, novelty questions in a professionally cynical game of “catch out the dumb robot”, I started using them to do things I have spent years learning to do. I write a pretty good strategy deck, I can read and glean meaningful insights from data, and I pride myself on being very good at organising information into neat columns in spreadsheets. The speed at which both tools could have a crack at those things when asked the right way is initially quite confronting. It casts many of the tricks of the white-collar trade as “busy work”, but by the end of the four-week course, I was asking myself why I’d ever spend time doing them ever again.

When we learned how to build a custom GPT, the penny really dropped, and the existential heat came off. Using the word “build” belies the simplicity of this task. It sounds very impressive, but no coding is required. I’d bet there are classrooms full of nine-year-olds who have known how to do this for a year already. Anyone can create a version of ChatGPT for a specific purpose, and it’s only as good as the information you give it and the instructions you write for it. As with anything data-related, it adheres to the old computing adage of “garbage in, and garbage out”. It is almost impossible to go big with this aspect of using AI at work as it demands you break down the most mundane aspects of your work and interrogate which parts of them could be carved off as either easily replicable or improved through collaborating with a generative AI tool.

This part of the course journey underpinned Shove’s distinct lack of charlatan hypeman energy — it was free of earth-shattering promises or threats and, ultimately, very useful. It’s also very apparent that using it to free up time and manifest AI’s great promises actually requires… time. The AI revolution isn’t hurtling at us at great speed but chipping away at things quite slowly.

To get my MiniMBA certification, I needed to write an AI use case. We were advised to keep it small and feasible and to check our thinking and draft using a generative AI tool like ChatGPT or Claude. The task was almost Socratic in this respect — you ask questions, the tool answers, and you continue to refine by continuing to ask questions.

Last Friday, over a few beers, someone asked me what the most exciting thing I’d done with a generative AI tool was. I need to find new people to hang out with, but I described the three-page business memo I’d written for the course and the custom GPT I’d built to simplify the process of writing design briefs. All very useful and all, reassuringly, quite boring.