Revered, feared and frank, Tony Astle has closed the doors on his fine-dining Auckland institution after almost half a century. Michelle Langstone heads to Parnell expecting to meet a tyrant.

Portraits by Simon Day.

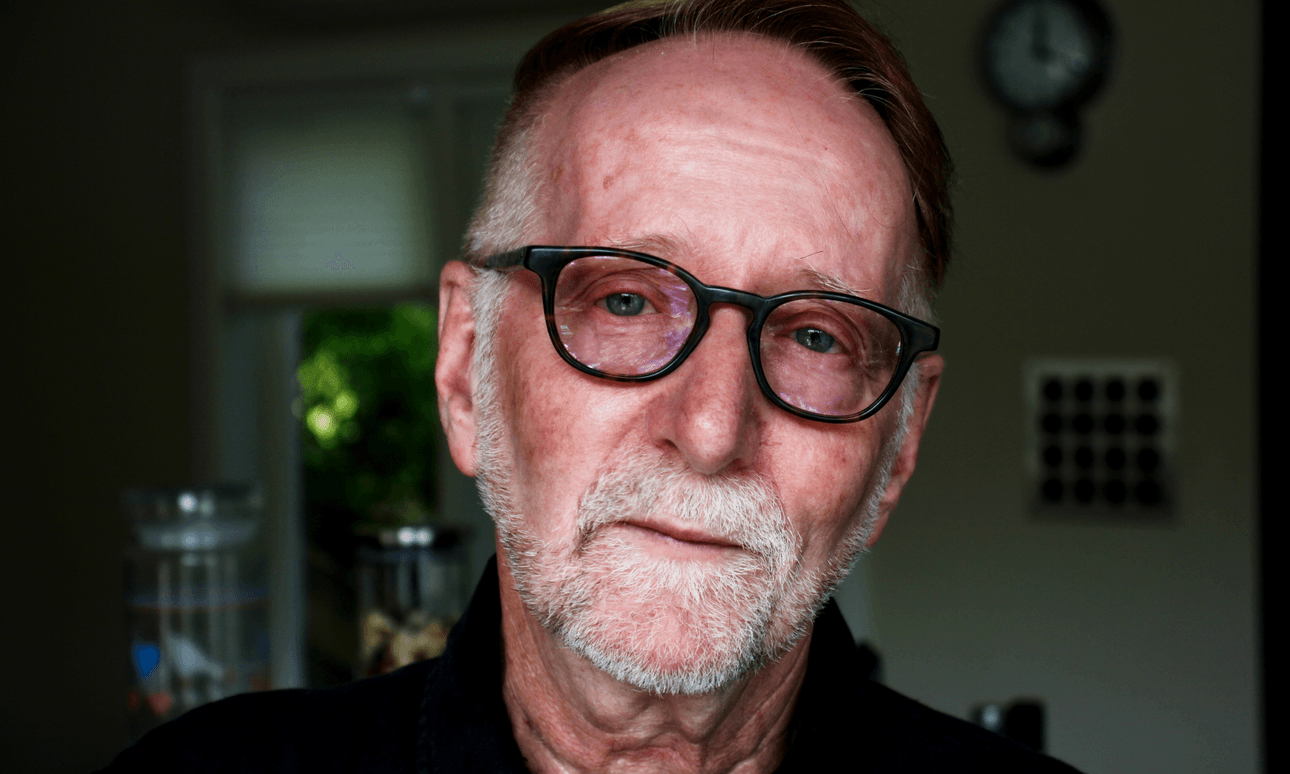

You know when Tony Astle is about to tell you a good story by the way his eyes start to gleam with mischief, and how he leans forward to rest his elbows on the table. At 70 he’s still as sharply presented as he’s always been – crisp black shirt buttoned to the collar, black pants, black leather loafers, his hair and beard fiercely in order, his spectacles gleaming. This morning I meet him at a little cafe just metres down Parnell Road from his former restaurant, Antoine’s, where he presided as head chef and, if the stories are to be believed, enfant terrible, for 48 years. Antoine’s closed for good in recent weeks, but Astle still comes to this cafe, the one he stopped at for coffee every morning of his working life. He hasn’t been into the empty restaurant this morning. “Too depressing,” he tells me, adjusting the gold watch at his wrist, and straightening the cuff of his shirt.

Antoine’s, the fine dining French restaurant nestled in Parnell Village, has been the stuff of legend for almost five decades: its food luxurious and expensive, its silver service elegant and unhurried. At the height of its power in the wealth-saturated 1980s, Antoine’s was booked out for lunch and dinner six days a week, and international celebrities, politicians and dignitaries visited whenever they were in town. Before the stock market crash of 87, Antoine’s was the place to be in Auckland, and everyone had an opinion about it – whether they’d dined there or not. A doorbell you had to ring to be vetted before you were allowed to come in. Customers barred entry for wearing inappropriate clothing. Diners spending thousands on dinners. Bottles of wine at $20,000 a pop. GST to pay on top of the bill and Eftpos never accepted. The stories are endless, and often outrageous.

At the heart of this culinary institution: a passionate and cantankerous chef who has as many foes as friends, a reputation in the kitchen for a temper, and beyond the kitchen for stirring up trouble. Astle famously banned both Helen Clark and Kim Dotcom from his restaurant. “I had no problem with Helen Clark – I just hated the way she was running the country,” he says of the former, and the latter: “I just thought he was so wrong, and I knew people who worked for him and he didn’t pay them. He was a very bad boss. They had to live there and cook for him and he treated them like crap. I just didn’t want him there, that’s all.” It didn’t help that Dotcom’s wife had requested a couch for him to sit on. You did not ask for such things at Antoine’s.

I expected something of a tyrant, but the man in front of me is mild-mannered, mischievous and generous, and it’s clear he wants to settle some scores on what he considers mistruths that have gone to print over the decades. The first on his list: the late magazine editor Warwick Roger. “I mean the first article ever in Metro was about Antoine’s being number one, and he wrote his editor’s bit about ‘If this is number one, I’m a dutch uncle blah blah blah…’ and he character-assassinated all my customers because they were wealthy. And wrote how I came from a wealthy family! I mean they didn’t even do their homework – wealthy family? Wish I did! I wouldn’t have gone into the restaurant business, would I?”

On the lastest episode of Dietary Requirements, The Spinoff’s food podcast, the squad discuss the legacy of Antoine’s and the place of fine dining in the Auckland hospitality scene. Subscribe and listen to Dietary Requirements via Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.

Astle grew up in Christchurch, his father was a truck driver, heavily involved in the unions, and his mother worked for the council. He is at pains to tell me his political leanings, as if I didn’t already know – he’s firmly, joyfully on the right. Astle has raised huge sums of money for the National Party over the years, and is vocally very fond of John Key. “You do know I’m not a left-wing person, don’t you?” he asks me early on, giving me an intense look, like he’s trying to get the measure of me. Until he left Christchurch, as a young man, he was a huge Labour supporter, he tells me. What happened to that left-wing kid then? It seems to have had a bit to do with his father: “He wanted me to go work for the railways, because you were ‘safe’ – a government job. Well he got sacked under them, because they were all finished. What changed me about that was he said, ‘Look at Norman Kirk’, because he loved Norman Kirk … I went off the Labour Party immediately.”

It didn’t help that Astle’s father didn’t want him to be a chef. It was “girl’s work”. They had a huge falling out, one that wasn’t rectified until shortly before his father’s death. At 15, Astle dropped out of school, keen to follow in the footsteps of his idol, Graham Kerr, New Zealand’s first celebrity chef. Astle wrote him a letter when he was about 13 or 14, and Kerr helped him to get his first job, at Le Normandie, the famous French restaurant in Wellington run by the fearsome Madame Louise. It was there that Astle lost some fingers in a meat mincer.

Unprompted, he thumps his left hand down on the table. Two of his fingers are cut off to the middle knuckle. He wriggles them, his expression gleeful. “Actually that is a good story, because I tell you what – Madame is dead now and so is her sister and her husband. I don’t want to denigrate them. I was mincing meat, and I put bones in it, because I didn’t believe that you should be using that meat – it was actually food that came back from the restaurant, and it was made into other things. I just put that bone in because I was so angry at having to do it. And of course the machine got stuck, and rather than get a hiding from Madame Louise – because she was quite rough, I mean in those days you never got away with anything – instead I took the guards off and put my hand in to get it [the bone] out. Luckily it was my left hand!”

I dare to comment on the instant karmic return on his actions, and he grins like a maniac. “It was! Totally! It served me right!” Astle went back to Christchurch to recuperate for several months, and only realised the severity of his injury, which was swathed in bandages, when he hit someone: “I was in Christchurch and I went out to a thing at the Civic theatre, and on the way out someone made some comment about me – ‘Wanker. What have you done to your hand?’ or whatever. And so I hit them with my hand and of course split all the stitches, and I was taken to hospital. Suddenly saw I had no fingers, and that was actually the worst thing that ever happened, because I could still feel them.”

Recovered and back at Le Normandie, Astle met Des Britten, radio broadcaster and eventual chef and restaurateur, who was to become incredibly important in his life. He also undertook 18 months of elocution lessons, to rid himself of the “Yeahgiddayhowarya” broad Christchurch accent he got teased for by the young staff at the restaurant. “I thought – I’ll fix you. I didn’t ever tell anyone. I’ve never told anyone. I went and had speech therapy – you know How now, brown cow and from then on … I tell you what, it works! It totally works when you speak properly.” It still makes Astle smile that people like Warwick Roger mistook him for a private school boy.

It’s important to place Astle in the context of a working class family, because it’s those humble beginnings of a self-confessed “horrible little boy” who was kicked out of Sunday school and taught himself to make Sunday roasts instead, that makes his ascent to culinary elitism even more remarkable. When Des Britten opened his restaurant The Coachman in Wellington, Astle went too, though he admits it was a bit stop-start. “I got the sack from there a couple of times. Just for answering back and being too cool. So I went home to Christchurch and opened a dairy when I was 17, Astle’s 7 day Mini Mart, with my brother. That ratbag, too-cool kid sold alcoholic milkshakes to high school and uni kids, which was against the law. He and his brother also hid condoms and sold them on the sly to the in-the-know customers. “We were down by the beach, so we had all the surfies. We stopped the populations growing! But that was all illegal, and of course I love doing things that are illegal! Anyway, we thought we were doing the community a service.”

It was at the dairy that Astle met his wife, Beth, who rolled ice creams. When he lost interest in the dairy business and went back to Wellington and The Coachman, she eventually followed. They married in 1972, and went overseas for a year. “But in the meantime I’d met someone that was going to go in partnership to open a restaurant in Auckland. So we went over there and I got jobs in France all the time, just easy jobs. I already loved French cooking. With Des Britten our go-to book was Mastering the Art of French Cuisine by Beck and Bertholle. It’s still the best book to teach kids basics.” When they came home in 1973 they opened Antoine’s, after the French version of his own name, Antony. Eyes twinkling at his own audacity, he says, gaily: “You think that was a little bit pretentious? We had the menu printed in French, in 1973, how bad is that?! We couldn’t even speak French! It was so good, and of course people thought ‘wankers!’ However, it was a huge hit.”

On the first menu: Astle’s now famous Duck and Orange. “It’s a monster, it’s still our biggest seller, and it’s an old fashioned one, you know – you get half a duck and the orange sauce is full of booze. It’s an old recipe that is neat to eat: young, old, it doesn’t matter.” The price? $1.95 – exorbitant in the early 70s. Astle’s beloved onion soup was also on the menu for about a dollar. “That’s still a huge one. Now it’s $30. People say, ‘Thirty dollars for a soup!’ But if you knew how long it takes to make it properly…you caramelise those onions for hours, and it has about five bottles of wine in it. I mean it’s not cheap! In fact I probably made less money out of that than I did out of other things.”

The beginning was huge. Astle, just 22, didn’t take a day off for several years, and the restaurant was always full. Simon Woolley, now famous for the Antipodes water brand, went to work at Antoine’s in 1974 as a waiter, and the legend of Astle’s temper was already in place. “One day he threw a cast iron pan through the hole in the wall that went through to the kitchen, and a dishwasher got in the way and he knocked her out. She was on the ground and I went to help her and he said ‘GET THE FOOD OUT!’ It was always amusing! He was pretty fiery. He was very passionate.” I put it to Astle that the trope of the chef’s temper is there for a reason and he protests, albeit mildly: “I actually didn’t have a temper, however, I got so frustrated … because I was a perfectionist and I wanted it done properly. There was no excuse not to.”

Simon Gault, who trained as a chef under Astle at 16 years of age, laughs down the phone when he tells me, “He made Gordon Ramsay look like a pussy! If it wasn’t perfect you would hear about it.” Astle had already warned me about what Gault would say: “Don’t listen to Simon Gault – he’ll tell you all sorts of things that aren’t true!” You can hear Gault’s exasperation and laughter on the phone when I bring this up: “One occasion, I cut a piece of meat for a steak tartare dish, and it wasn’t the right size. So it came flying back at me. I literally took two steps back and caught it with my good cricketing skills. And he was so annoyed he came and got it off me and threw it at me again.”

It sounds like a temper to me. I ask Astle what the worst thing he thinks he’s ever done is, and he takes his time to consider this, rapping his knuckles lightly on the table top, a smile tugging at his mouth, before looking me right in the eye and announcing: “Probably the worst thing I ever did was stab someone.” I make a sound like a cat being strangled and his grin widens. “It wasn’t on purpose, but it was one of those spur of the moment things. What people don’t seem to realise is in those days we were so busy and the turnaround was … you were just tired. You shouted a lot because that’s what happened. In those days everyone shouted a lot!” I’m staring at him, mouth agape, and he goes on. “There was one boy, and I actually think about it all the time. I was giving him so many chances, and it just wasn’t working. And one night I was just so angry I just slammed a knife down, and it just happened to have his foot below it.” Astle mimes violently chucking a knife at the ground and watches me for my response, which is still appalled, but also fascinated. “Anyway I just pulled the knife out and off he went and off I went, and I didn’t say anything. And all of a sudden Beth said, ‘Is he all right? He’s very white.’ And I said, ‘He’s just hopeless!’ And then I said, ‘What’s wrong?’ And he said, ‘I feel dizzy.’ I said, ‘sit down,’ so he sat down on the ice bucket. At the end of the night he took his shoe off and there was just blood everywhere.”

Today, Astle feels bad about the way they wrapped him in bandages and bundled him off to the hospital at the end of his shift, and how that boy never even told his parents what had happened. But four years ago, he got a surprise. “The doorbell at Antoine’s rang, and I opened the door and went, ‘Oh my God!’ I recognised him! And his kids, they were eight or nine or whatever, and they said, ‘Is that the man that stabbed you, Dad?!’ Astle’s full laugh is a loud, staccato HA HA HA HA, and he erupts into it now, delighted with the whole story.

For all that, both Woolley and Gault say Astle was terrific to work for. Gault is quick to defend that famous temper: “He was a perfectionist, and for a young chef starting out it was the best training you could have. Everything had to be done perfectly because he cared beyond belief. The way I see that is it’s the best training you could have. You don’t want to work for somebody for whom average is OK – you want to be above average.” For a kid like Gault, it wasn’t just in the kitchen that the learning happened. “He was amazing. He was a mentor in all facets of life, not just cooking. He would advise you on everything, like how to invest your money. Because obviously as a 16-year-old, if you worked nights, you don’t get to go out and spend your money, and you’re living at home with your parents at that stage, so it was a reasonably good saving routine, and he would tell you how to invest it.” I ask Gault if they were good investment tips and he doesn’t hesitate. “They were! They were very good!”

Of Astle’s legacy, Gault says this: “I always thought, especially after I left Antoine’s, that Tony was ahead of his time. He was at the leading edge of what was going on. Tony travelled every year. It was always really exciting because he would close the restaurant, and he would go to Europe, and he would come back and it was always so exciting – what was going to be on the menu?! It was not what everybody else was doing. It was real food. He tasted everything – every sauce that walked out of that door. Everything was made from scratch to order.” Simon Woolley credits Astle as the reason he stayed in the restaurant industry, and the pair even opened a gastro pub down the road together: “He was amazing, he was always very supportive. When I left he didn’t really want me to leave and do my own thing. Even when we had our business together I’d still work the six dinners up at Antoine’s. I’d go down to Exchange and have 150 people for lunch and scream home and have a shower, get changed and be back at Antoine’s and work at night. I wouldn’t have stayed in the industry if it wasn’t for Tony’s support.”

Both Gault and Woolley worked for Astle in the hedonism of the early 1980s, Astle’s favourite time in the restaurant. In the cafe, he begins to tell me his best story: “I think the best night I ever, ever, ever had,” he says, hitting the table with every ever. “The best night ever was so funny: Elton, Rod Stewart and George Benson were there for the night, all three of them. About five in the morning we’re sitting outside, probably all smoking and doing things that you’re not supposed to be doing.” He was out there so long his wife turned up, and wondered if she’d caught him in some kind of tryst. “Beth started work at 6.30 every morning, and she came to work and came in the back door as she does, walked through and thought, ‘Finally! I’ve caught him out there with someone!’ And she walked out and there was Elton John, Rod Stewart and George Benson … and me! Sitting there drinking champagne and getting up to mischief. She went: ‘Oh my God!’ and just turned round and went home. Couldn’t cope. That was such a neat time.” The grin is a mile wide. Elton John visited Antoine’s every time he was in New Zealand. Simon Gault remembers sitting down with him and the other staff, just chatting after hours, and how he played tennis with one of the waiters on the weekend. Rod Stewart was a regular customer, especially when he was married to “that ice cream licker” Rachel Hunter. “Then he came in one night with the new one, Penny Lancaster. He said, ‘I don’t believe I’ve been here before,’ and I thought: well that’s bullshit!”

A carousel of politicians made it through Antoine’s. Astle, a politics fanatic, can recall them all. “David Lange, even though I hated the thought of him dining there, he was actually fantastic. And he loved his food in those days, but then of course he stopped eating. Which is sad. He was a good person. Roger Douglas was fantastic. He was too right wing for the Labour Party – that’s why I loved him of course.” Having banned Helen Clark, would he ban Jacinda Ardern? “No, she just wouldn’t come. I know she wouldn’t come. It might be a bit elitist there, and plus there’d be no one there who would vote for her.” For the record he thinks Robert Muldoon, despite being National, was “an awful man”, and Mike Moore “a neat man”. He loves Judith Collins, and I remark it must be because she’s also a troublemaker, and he smiles and wrinkles his nose up with pleasure: “Birds of a feather! I just love her, although she’s got a bit soft! She’s getting far too soft! She’s a good person. She is actually a lovely person. And she had that image – it probably isn’t really her – and she’s probably being more natural now, but it’s too left wing for me.” He’s on the David Seymour bandwagon after the last election, fixing a hoarding in the restaurant window’s interior so it couldn’t be defaced. He even left it up there on election day, though he knew it was illegal. But then he does love illegal things. I call him a low-rent criminal and he laughs. “I am! Totally!”

Astle also loves American politics, and had a great time in the recent elections, going on Facebook to rark people up. “Of course I stir a bit, because every time I saw something about Mr Trump, I’d go and say, ‘I love Mr Trump!’ I can’t believe how people just want to kill you! It’s so sad! I mean this is all tongue in cheek stuff!” He says he’s learned over the years that stirring things up is a great way to get a bit of publicity, particularly if you don’t care what people think of you, which he assures me several times, he doesn’t. “If you Google ‘Tony Astle’, the first thing that comes up is – I think it was Michele Hewitson – ‘Tony Astle will not employ women or fat people.’ Of course I said that! It was tongue in cheek! I’ve had about 35 women staff! We’ve had so many women – my wife worked there for 48 years for God’s sake! So it’s just funny.”

Astle is not shy of an opinion, and it’s very funny when he gets going on some of his pet peeves. On kicking out badly dressed would-be diners: “You don’t come to Antoine’s in jandals and shorts, no matter who you are! I mean I’ve never worn shorts. Well – at high school I did. I’ve never worn jandals. I’ve never even gone to the beach! I don’t like sand. And I hate water.”

On cell phones on tables in restaurants: “I think it’s disgraceful and they shouldn’t be allowed. I didn’t have wifi! The best story ever was about two years ago we had this group of very sophisticated young Asian people, really well off obviously, and they were sitting there and everyone had their phone, and they asked the waiter. ‘We want wifi.’ I came round and said ‘Have you got a problem?’ ‘We want wifi.’ I looked at the menu and I said ‘No, we’ve got duck and orange, onion soup … no wifi!’ They got up and left. They could not cope without their phones.”

On the plant-based food movement: “Ugh! I’ve tried it and I’ll tell you what I did in the supermarket, and you can write this, I don’t mind. When I go to the supermarket I look at that ‘meat’ that’s near my meat, and I go ‘What the hell is this?’ And then I move it to another part of the fridge.”

Astle has never been afraid of speaking his mind, or throwing people out, and he’s even occasionally called the police on diners. The band KISS came into Antoine’s, and one of the waiters dribbled a bit of white wine on Gene Simmons’ shoe. “He went apeshit, said he wanted to see the owner. I was very young at the time and probably more bumptious than he’d ever met in his life. He said, ‘Do you realise we’re not paying for this dinner?’ I said, ‘Of course you’re paying for it.’”

Simmons also demanded Astle pay for his shoes, which was scoffed at. “I said, ‘Excuse me? I wear $1000 shoes and I cook in them and it doesn’t seem to worry me. You’re a wanker.'” None of this went down well, and eventually Astle called the police. At this point in the story he’s giggling like a naughty child. “The police came and said, ‘If you’re not paying, you’re going to jail.’” The band paid. “They were awful! I hated KISS anyway, so it was perfect for me.”

Despite the odd disgruntled diner, Antoine’s was making a small fortune, allowing Astle to travel the world discovering new cuisine in style. He and Beth took the Concorde to France one year: “Beth would never sit next to me on planes because she said I drink too much, so she was in front. And Concorde only have two-and-two [seats]. I’m sitting there and the next thing someone sits down and says hello and it was Roger Moore. We got chatting and he said, ‘What do you do?’ And I said, ‘I’m a cook.’ His friend was sitting opposite, and he said, ‘Who are you sitting next to?’ And Roger said, ‘A cook from New Zealand.’ And the guy said, ‘Must be a fucking good one to be able to afford to be on this plane.’ He was fantastic, we had the best time. And Beth sat next to an actor from Dallas.”

Simon Woolley remembers the 90s, when Astle and his restaurant seemed to go out of style. “Everyone was on this bandwagon that Antoine’s was so passé, that French was so passé, but in the rest of the world, French restaurants were still huge. I was in New York when Balthazar opened, and that was this big ‘Oh my God this amazing French restaurant in the city’ and by that stage, in 1997, New Zealanders were completely over French.” Like all enduring classics, Antoine’s came back into style, though perhaps more modestly than in its heyday, and until its close it remained one of the most respected restaurants in the country. Astle was awarded an ONZM in 2012 for services as a chef.

His passion for cooking has meant, with the exception of those overseas trips, he has worked almost every day in the 48 years Antoine’s was in business. In the three years they worked together, says Simon Gault, Astle took only five days off. Two services a day, six days a week, long hours in a little kitchen with cranky stoves that nobody else could work. Gault says he and his wife are the hardest working people you could imagine – Beth cashing up at the end of the night, awake first thing the next morning to clean the restaurant, her husband in the kitchen from early morning until well after midnight, for decades. “I called in not that long ago, just to say hi, and there he is in the kitchen, on his own in the morning, cooking away, getting everything ready. He’s done that for so many years, he must feel like a spare prick at a wedding at the moment, you know?” Astle says he still wakes up at 6.30 each morning, programmed that way for an early start. He’s starting to stay up later and later at night, in the hope he can finally sleep in. He spends a lot of time regaling me with anecdotes, but I think part of that is he doesn’t want to sit in the feelings of what it’s like to close his beloved restaurant. It’s been his home, he says simply. “I spent more time there than I did in my own house.”

Simon Woolley helped him clear out Antoine’s when the restaurant closed, and it was a cathartic experience. The contents of the restaurant were taken away to an auctioneer. “It was hard to watch him go through it. The auction house came and he’d see the restaurant chairs go, and it was quite emotional for him, obviously. He’s spent as long as I’ve known him inside those four walls. He’s spent his life there, you know? He’s sort of like me probably, where outside of work he didn’t have any hobbies – when you work day and night for 40-odd years you don’t create hobbies because you’re working nights. You’re way out of tune with what people do.”

One of the things that touches me most is the way Astle seems lost when I ask him where he likes to eat. It turns out it’s yum cha, because for many years it was only Chinese restaurants open on Sundays, his one day off. Now he’s got to start thinking about where to go. Mr Morris, Michael Meredith’s new venture, is on the list. Like Gault, Meredith trained under Astle. Aside from that, he doesn’t really know. While I’ve got him thoughtful, I ask if he has any regrets across his career. “I always wanted to be a school teacher and help kids.” He and Beth never had their own children, and he takes a moment when he tells me they “never had time”. He muses on it, giving his head a little shake, and I can see where a twinge of regret sits inside him, before he smoothes it over: “Probably all the restaurant kids, they were my kids. We had so many of them. We see them all the time. Every time they’re in Auckland they come and see us.” I repeat this to Gault down the phone and his voice quivers: “Oh boy – I’ll get emotional now! It was pretty special times. Christmas was… we worked Christmas day, but then there was the party afterwards and the presents. There was never any expense spared. Beth was a hairdresser previously, so she used to cut my hair, and any girlfriend problems I’d go to Beth. They were kind of like parents really, because you lived there.”

Antoine’s has closed for personal reasons, says Astle. He’s unwilling to be drawn on the details, but you can tell by the heaviness in him that it wasn’t an easy decision. What to do with his time now is the question. He thinks he might like to open a commercial kitchen, and reproduce some of those incredible sauces for people. Customers are still trying to order his famous tripe, he laughs. A little commercial venture to occupy his time, Antoine’s name adorning packages of sauce, the legend living on. All the proceeds will go to charity, most likely Cure Kids, with whom he has a long association. He’d also like to mentor young chefs if he could.

We go out blinking into an absurdly pretty day, and in the sunlight I remark how much his outfit resembles a chef’s uniform, now I can see it properly. He laughs and tells me Beth said the same thing. “I had to look nice for the interview of course. Very important.” We walk side by side up Parnell Road, chatting away until we reach the site of his former restaurant, and his face twists with feeling. “Look at that. The sign is gone. Look how awful it looks.” He reminds himself that he must take the little brass doorbell home as a memento – it was his grandmother’s. He shows me the front courtyard, softly green with plants. “That’s where I sat with Elton John.” In the far corner, a bird bath is almost empty of water. Tony Astle gives a little shrug of his shoulders and moves on up the road.

Read more Michelle Langstone interviews here.