Uther Dean reminisces about how kids’ games were used to trick him into enjoying his education – and how those games still hold up today.

Do you remember the days of the old school yard? We used to laugh a lot. Well, people used to laugh a lot. I don’t know about you but I certainly wasn’t in the school yard. I was laughing, yes, but I was far from the dangers that populate the schoolyard: the bruising bark-chips, the sharp grass, the physical movement. I was inside learning like a chump.

Let me be clear: I did not know I was learning. I thought I was having fun. One of the eternal betrayals of schooling is its addiction to the secretion of learning (a not fun thing) within fun (definitionally a fun thing). Sometimes it was as simple as songs (fun) that taught us about numbers (not fun). Sometimes it was much more complicated. Which brings me back to why I don’t remember the days of the old school yard. I was playing video games (fun OR SO I THOUGHT).

The class had a couple of computers and we were allowed to use during breaks but only on approved programmes. When I first saw there was a game on the list of approved programmes, I was sure some mistake had been made. They wouldn’t just let us play The Logical Journey of the Zoombinis, would they? But it was on the list and I was more than ready and willing to abuse this seemingly oversight. Even when I was only a few years into primary schooling I was on my hustle. Little did I know, I was the one who was being hustled.

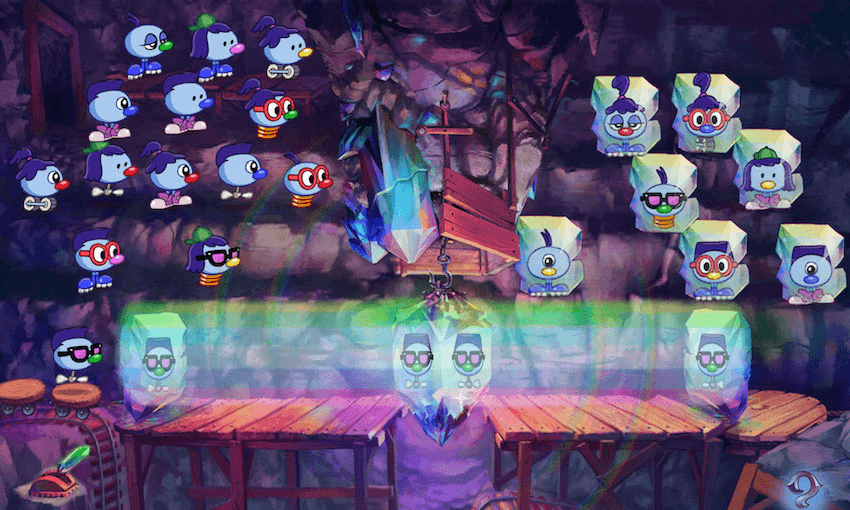

The Logical Journey of the Zoombinis (more recently re-mastered re-released as just Zoombinis; you can get it on Steam) is a thrilling game where you guide blue little creatures (the Zoombinis, obv) through a series of challenges to help them find a new home. You have to cook a squat troll a pizza, you have to trick some of the tall, edgy Fleens to attack themselves with bees, you have to sit on a raft in the right order. You know, standard video game levels.

Playing it again as an adult, I can see that Zombinis’ masterstroke is the character creation option. You move the Zoombinis in groups of 16 and each time you start out with a new group (you win the game when 625 Zoombinis make it to their new home, something I’d suspect very few people have achieved), you can design each and every one of your charges.

The character design may seem shallow by the standards of today’s pixel-perfect self-replicators but the five options each for hair, eyes, nose colour and feet are the precise right amount for you to build your own little cast of characters – each with their own distinct attitude and personality. You care about your Zoombinis, you’ll do whatever it takes to get them to their new home. This was true was true in 1996, playing it when I was six or seven, and it was true in 2017, playing it when I was 30.

I cared and I engaged. Which is what made The Logical Journey of Zoombinis’ betrayal all the more painful. It slowly dawned as I filled my school breaks with Zoombanity that something didn’t seem quite right. Days had passed and it was still on the list of approved programmes. And something strange was happening. I was becoming more logical.

I could decode patterns in the world much better. I started to be able to figure out how things could relate without being explicitly connected. This was odd. We hadn’t talked about this at school. It was just happening to me.

My first thought was that I was a genius. That is always my first thought.

My second thought is always that I am definitely not a genius.

Then I remembered the Zoombinis. I remembered how I would work out which of the two sneezing bridges to send my Zoombinis over (one was allergic to blue noses, the other allergic to everything else). Then… I remembered the name of the game. The LOGICAL Journey of the Zoombinis.

I’d been had. I’d been playing a game (fun) but learning (not fun), but it didn’t feel like I’d been learning (so it hadn’t been not fun). I have struggled with trust issues ever since.

But that didn’t stop me playing the game. I wanted to get all those Zoombinis safe. All 625 of them. It took a hell of a lot of lunchtimes, but I did it. All of my wards with their little noses and their little lives got to their new home. Yeah, I learned, but that wasn’t the point, that was a by-product. I didn’t like it, but I loved the Zoombinis so I beared with it.

Which was going to be the final point of this piece: that what makes learning games successful is that they have to be good enough games to hide the learning. The spoonful of sugar has to be sweet enough. That the secret of that lies not in mind blowing graphics or physics or explosions, but in allowing people to buy into the characters.

In short, Zoombinis are the best educational part of Zoombinis because you love them enough to learn.

That was going to be my final line. But then something happened.

I couldn’t stop playing Zoombinis. I bought it just to give it another go for this thing, to remind myself of how it was. I wouldn’t spend more than hour on it.

Oh, I was a fool. How soon we forget the ones we love once they are out of our sight. Time may have robbed me of my innocence but it has not done the same to the Zoombinis. They are the same pale blue wonders they always were. The remaster has updated a lot of the graphics but hasn’t fixed what isn’t broken when it comes to character design.

The Zoombinis’ wide eyes still stare out at you, begging you to care for and understand them. Pleading with you to get them home. You make a family of Zoombinis, and then you save them. You can’t say no to that.

I was going to be here for much more than an hour.

Partly, this was because of the Zoombinis but also because it turns out that Zoombinis is still a challenge when you’re six times the age of the core audience. The learning curve is not so much painful as persistent. This is exacerbated by the dopamine-dampening insistence the game places on deliberate failure. You have to be wrong to deduce what the right pattern is.

This should make the game unsatisfying but instead it makes it compulsive. Removing the fear of failure means that you are free to try anything. The worst thing that can happen is that you lose a Zoombini or two and they can be collected from a campsite later in the game.

This makes the game mediative and calming. By understanding, the Zoombinis’ world, I was starting to understand my own better.

Which is to say: oh shit, it started teaching me again and I am a grown adult.

Turns out that good educational video games work for everyone. Or maybe I’m just stuck being six forever.

But either way I know one thing: I am getting all my damn Zoombinis home.

This post, like all our gaming content, comes to your peepers only with the support of Bigpipe Broadband.