The South Island’s snow and ice act as a battery that powers our food systems, by storing water to ensure the rivers can keep flowing and the soil stay hydrated year round. So what does it mean when all that frozen water is melting?

In the middle of winter, the water is cool, but not icy. The salmon swim in man-made hydro canals, the water connecting three alpine lakes to the country’s biggest hydro electricity scheme. The alpine origin is obvious: the water is milky blue from the rocks that the glaciers across the lake have ground into flour. The salmon gleam in the pen, silky silver and green.

“The temperature is a bit wearing on humans, but the fish don’t mind,” says Jon Bailey, the general manager of aquaculture at Mt Cook Alpine Salmon, in the Mackenzie region in the central South Island. “They’re very adaptable.”

The fish live their whole lives in freshwater, wriggling in the current of the canal, and when they’re ready to eat, Bailey describes them as tasting “buttery”, almost like silken tofu. There’s a distinct “cleanness”, he says, to salmon raised in freshwater, as opposed to saltwater.

The freshwater that the fish live in comes from the mountains – and with its name referencing Aoraki and photos of the Southern Alps all over its website, Mt Cook Alpine Salmon is definitely keen to emphasise that. Snow falls in the mountains: some of it settles and compresses into creaking glaciers, some of it melts in the sunshine and follows gravity all the way back to the ocean. In between, Bailey’s salmon swim in it, some of the water spins propellers in hydro dams, keeping the lights on, and farmers use it to hydrate their land.

“Ice and snow are part of the whole cycle – the journey of water from the mountains to the sea,” says Justin Tipa, kaiwhakahaere of Ngāi Tahu, the biggest iwi in the South Island. That cycle is acknowledged in place names; the Waitaki River, which drains out of the Mackenzie Basin close to Mount Cook Alpine Salmon, has a name that translates to “the tears of Raki” – the sky father whose tall son, Aoraki, stands at the end of Lake Pūkaki. For Ngāi Tahu, gathering food was enmeshed with rivers and the snow that fed them: for instance, the Waitaki was an essential route for mahika kai, the gathering of food, and known for its abundance of eels and weka.

Given the interconnectedness of food and water – and also snow – changes in weather patterns can have significant effects. Niwa’s seasonal climate outlook predicted that this winter would be drier than last year and temperatures would be average or above average historical norms, meaning less rain and snow. Glaciers are melting far, far more quickly than they are being replenished. In the long term, shifts in rhythms of snowfall and snowmelt will have consequences for New Zealand’s food supply, from dairy, vegetables, grains and – obviously – gourmet fish. What those consequences mean isn’t totally clear yet – but it’s increasingly obvious that the effect of that melting snow can’t be ignored.

A leaking battery

Snow falls most when it’s winter, of course, when there’s also plenty of rain in areas like the Canterbury Plains, which produce lots of food. In summer, when the weather is drier, the snow melts, having effectively stored winter precipitation and released it when there’s less water around. “Snow is absolutely critical for maintaining river flow during the summer months,” says Niwa’s Christian Zammit, a hydrologist who studies freshwater catchments and how they are affected by climate change.

Niwa’s annual survey of 48 New Zealand glaciers has shown that they are emaciated, exposing bare rubbly rocks and creating lakes that used to be ice. Still, the survey allows scientists like Zammit to estimate the volume of glacial ice in New Zealand – about 36 cubic kilometres, almost entirely in the South Island. That doesn’t count less permanent snow. “Don’t ask me how many swimming pools that is, I haven’t done the conversion,” Zammit says.

Because of its “storing water in winter, releasing it in summer” quality, New Zealand’s ice and snow can be described as “sort of a battery – and the battery is leaking”, says Zammit. The climate at high altitudes is warming even more quickly than in the lowlands: Zammit describes how “the higher you go, the larger the temperature compared to coastal areas”. A two- or three-degree temperature change in a low city like Christchurch could be as much as eight or nine degrees in the sensitive alpine environments. At negative three or four degrees, the snow stays in place; at four degrees, it’s already melting. “By the end of the century, current projections indicate that most of New Zealand’s glaciers will disappear,” Zammit says. Thirty-six cubic kilometres of ice: a very big puddle dripping into the sea.

It takes a long time to melt all that ice, all the same, because water is very good at holding heat: think of a hot water bottle tucked beside you at night and still lukewarm in the morning. That means it might be a couple of decades before snow loss means rivers run dry in summer – for a while there will be more water melting – and it’s difficult to separate the role of ice from other climate factors: warmer temperatures will also mean more evaporation from the sea and therefore more rain in some areas.

Bailey, for instance, isn’t too worried about his fish running out of water for now: the level of water in the hydro canals is regulated by the power companies to keep the flow constant. In spring and autumn, the water is topped up by rain; in winter the snow builds up, and in summer it’s released again. “The canals flow hard and fast most of the time – we go with the flow.” He pauses, then we both realise he’s made a pun. Changing water temperatures are more of a concern – marine heatwaves have killed thousands of fish in ocean fish farms. “They get uncomfortable and stressed at 18 degrees, and they stop feeding at 20.” Occasionally the water will get up to 17 or 18 degrees on hot days in February, and Mount Cook Alpine Salmon is expecting those days to occur more frequently. Warmer water holds less oxygen, too, which can be bad for the fish. “We might see more water [temperatures] in the upper ranges for salmon, but we believe we’ll be OK – fish welfare is number one.” The company also expects to have to adapt to more frequent extreme weather events, like heavy rainstorms – but that hasn’t affected the salmon for now.

From snow to irrigation

Further away from the mountains, in the lower reaches of the South Island’s big rivers, commercial food production is assisted by water drawn from rivers. Irrigation helps grow grass to feed cows and sheep, and to water plants. “We see water as an enabler: it enables you to grow veges or fruit or wine grapes or plants to feed animals – it gives us choices,” says Vanessa Winning, chief executive of industry group Irrigation NZ. While lucrative exports – beef, dairy, kiwifruit, lamb, apples – do require irrigation, Winning says that New Zealand’s “thirstiest food” is largely consumed here. Most vegetables, which require extensive irrigation, grown here are eaten in New Zealand and grains – much of which ends up getting fed to animals – stay onshore too.

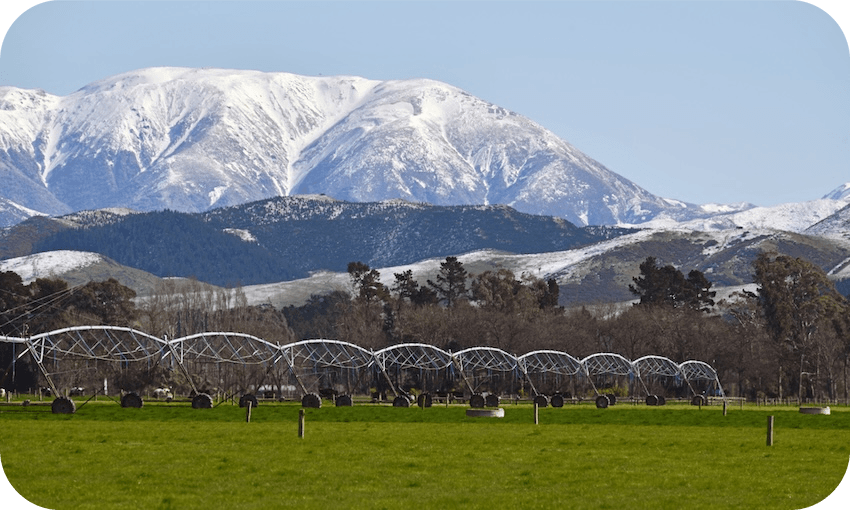

Technological shifts have changed the efficiency of irrigation: Winning says that flood irrigation, where the water runs across the land, has largely been replaced by spray irrigation, like the wheeled metal systems you see in fields. Still, she says that 80% of water doesn’t penetrate into the ground but is lost to evaporation: snow turned into water turned into air. Other techniques, like drip irrigation and hydroponics, can increase the efficiency, as can mixing crops. A dairy farm that grows spinach as well, an orchard with some space for wheat. As New Zealand’s climate changes, Winning says it will be necessary to learn from places with more water restrictions, like the Middle East and Australia. “We get fantastic info and technical growth from dry parts of the world.”

Winning says that three- or six-year government cycles aren’t long enough to make long-term decisions about water. “Successive governments haven’t been good at strategising.” As the climate changes, she would like to see it become easier for farmers to store water in dams or reservoirs on their own land, known as “on-farm storage”. In her view, this would make farmers less reliant on changing water levels due to reductions in snowmelt or rainfall in areas like North Canterbury, and make it easier for rain, when it does come, to be saved for dry weather. Current minister for regional development Shane Jones is supportive of more water storage for farmers, including that consented through the fast-track bill, and the National Party pledged to reduce restrictions around on-farm storage as a key election promise. With on-farm storage, Winning says “you can still operate, without taking from the river.”

On-farm storage isn’t without its detractors, given New Zealand’s freshwater crisis. Scientists have criticised earlier rule changes around irrigation: under the previous National government the amount of land in New Zealand that was irrigated increased massively, while river levels dropped and nitrate pollution entered aquifers. Marnie Prickett, a freshwater advocate, pointed out to Newsroom when the election policy was announced last year that storage “doesn’t become insurance for a rainy day, it becomes a central part of your farm system”.

Water stored in dams and reservoirs to put onto the soil is water that isn’t flowing in rivers, providing a home for freshwater animals and carrying water to the sea. Winning emphasises that “we don’t want to stop it going out to sea – ecological support for our rivers is important”, but acknowledges that solutions can be controversial. “There’s a lot of shouting at each other to get our point across.”

For Ngāi Tahu’s Justin Tipa, with the iwi’s case asserting rangatiratanga over freshwater against the Crown still before the courts, the concepts of Te Mana o Te Wai must apply to all decisions around water usage. The policy framework emphasises the health of freshwater systems in a hierarchy: first, the ecosystem, then human’s ability to access clean water, then other uses of water, like for agricultural irrigation. “We depend on water for people and the economy to thrive,” Tipa says. However, the government wants to remove the hierarchy as part of its resource management reforms.

Tipa notices the role of rivers when he walks around a supermarket. That jar of yoghurt, those courgettes, these squiggles of mince: all made from water. According to Environment Canterbury, 85% of Canterbury’s groundwater is allocated for irrigation: snowmelt trickling into dark, cool aquifers under the ground gets spread across bright green fields on hot days. “Ice and snow are part of the whole [water] cycle – we need to think about them to mitigate and adapt to climate change.” He wants to invite people to feel the extent of deep connection to the land in the food they eat and the landscape around them: to cross a bridge and notice how much or how little water echoes in the riverbed below.

“We’ve noticed spring floods earlier in the year, less overall snowfall reducing natural [water] storage, high temperatures in the water – that’s not conducive to good life in water.” Tipa, who has worked for Fonterra in the past, doesn’t want to villainise farmers. “We know growing animals and growing food needs water – but there are better ways of doing it.” If the court case is successful, and crucially, if the hierarchy of Te Mana o Te Wai remains in place, Tipa believes that practical knowledge from Ngāi Tahu and their ancestors can keep looking after the water for future generations. Snow and ice, rivers and creeks, oceans and rain, all in the same system.

Many people don’t see the shining lines of the mountains across the plains like Tipa does, but the snow they hold helps feed us all. For Tipa, it’s visceral. “I’m a kai gatherer, I’m eeling, I’m fishing, I’m in the rivers. The freshwater feeds my family.” He wants that possibility to stay open. “We need a sustainable water catchment for generations.”