Stuff debuted a pretty new design this week – but it, like all of us, still has to live with the tyranny of horrific online ads. Why?

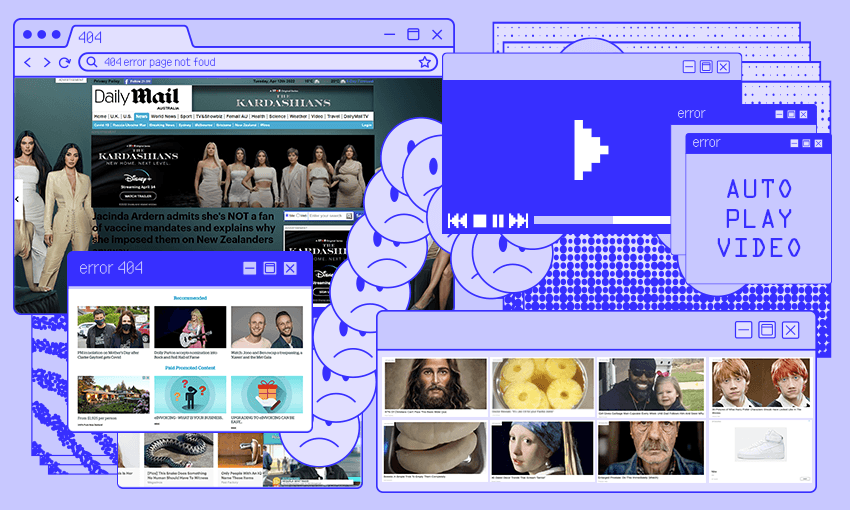

I have a folder on my Google Drive called “journalism online looks like shit”. I’ve had it since 2018, and have dutifully filed away examples of egregious pile-ups of display advertising, link stacks, homepage takeover horrors and chum boxes (the Outbrain bizarro world at the bottom of stories) as I’ve encountered them since. We all have our hobbies, and this is mine.

When I started doing it, I wasn’t quite sure why. It annoyed me, the way it made reading the work of my fellow journalists an exercise in trying to find fragments of text amid the scree. I was also certain it wouldn’t last – couldn’t last.

The biggest frustration is that the weight of advertising and internal distraction obscured the good, sometimes outstanding journalism, performed by organisations under immense pressure. The New Zealand news media operates in a difficult financial environment, with print still heavily subsidising digital, social media users harshly critiquing its work and worth, and with complex news events happening far too frequently. Rather than supporting its work, the advertising can often make it near-impossible to read.

What I struggle with is who is really being served by this approach. The majority of advertising on news sites is nominally about brand or awareness, and yet it seems almost certain to generate negative brand association the way it’s so carelessly deployed. So it seems bad for the brands involved. The journalists who create the product have it sliced into pieces and obscured, a bleak fate for difficult and important work. The audience has to try and navigate a visual maze, a terrible user experience. Even fancy new design schemes like the very thoughtful one Stuff rolled out this week feel like they’re battling against the voracious demands of unfeeling ad units.

Who wins? The only people, as far as I can tell, are the brokers in the middle. The digital ad market is dominated by media agencies, which decide where the money goes, ad tech companies, which facilitate that distribution, and display networks, dominated by Google, which can take anywhere up to half of the revenue associated with an ad. It feels phenomenally complex by design, and like it works entirely for those who own or manage the pipes, and not all for that trinity connected by those pipes – the news organisations, the audiences and the brands.

Why do we have ads on our news sites anyway?

Ultimately, most journalism has for centuries been a product for which the consumer pays only a portion of the cost of production, with the balance paid by advertisers that buy access to that audience. While news readers have heroically stepped up to pay more of the cost of production, for most news organisations, from small independents like us to giant global organisations like the Guardian, somewhere north of 40% of income comes through advertising.

This seems unproblematic at its basis, and worked well both aesthetically and financially – until the internet arrived. Then it all went to visual hell, making no one happy. I decided to call a friend who works in a senior role at a large media buying agency to talk through some of my collection of screengrabs, and have him give a critical analysis. That is, to ask someone who really knows why this happens. We agreed to anonymity because he still works in this town, and didn’t want to be seen to criticise either media organisations or brands. So I’ll call him Brian.

Brian’s answers show that the causes of this problem are surprisingly complex, and there is no clear villain in this piece. We as news media deserve a hearty slice of the blame. Creative agencies are not without sin. Brands themselves play a crucial role. Probably the biggest issue is the massive increase in inventory, with advertising everywhere from within your Uber and Amazon apps, to Trade Me, to search to social and more. Tellingly, many of the most powerful new players have no content costs.

Yet Brian agreed that media agencies have not done a great job of pushing the form forward. His main issue was that we’re still measuring the wrong thing. His thesis is that it was born wrong – that because we could measure an impression (how many people might have seen it) and a click, we decided those things were most important for the display ads that dominate most news sites. Whereas with video ads, which dominate social, we don’t expect a click.

“The internet is videotising quite fast, right? So creative agencies and clients made a predetermined split, which said ‘anything brand-y I’ll do in video,” says Brian. “And everything else, that’s direct response. That’s how we chose the metrics that matter. Which is quite an artificial construct.” He says this meant there was an expectation that news sites generate traffic to brands’ own sites, which is to say that news and magazine sites were lumped in as direct response (basically the online equivalent of coupons and junk mail), while video on YouTube or TVNZ OnDemand was seen as a brand play. Brian sees that as a wholly artificial division traceable back to the earliest days of the web, but which is somehow still hanging around.

There are literally hundreds of examples of horrible online ads on news sites (I have that folder, remember), but I thought it best to run through five archetypal examples of ugly, confusing and generally unpleasant online content display to get a sense of why it looks like that. At the end, I got a tantalising glimpse of hope for a better future.

DISCLAIMER: I am obviously riding for a fall here. No one publishing online media can guard against calamitous failings at the intersection of ads, technology and content. So while some of these examples are taken from our local media, this should properly be understood as a plea for improvement as a whole, rather than a critique of what currently goes on at any individual publisher.

1. The vast and often broken homepage takeover

The homepage takeover is one of the priciest items in digital journalism – clients pay upwards of $20,000 to submit users to a barrage of brand on arrival. (Related: the auto roll-down on the Herald, and Stuff’s full blackout to draw attention to a single display ad). These often seem to cut off half the product being advertised, while also making it seem janky and broken by association.

“Creative agencies have got a role here,” says Brian, who believes they were once places that saw true creativity in areas like this. “I don’t know what’s happened.” He says that while different specs (we’re all on different devices, which makes one-ad-fits-all hard) and size limits have an impact, the main issue is that these are a bolt-on at the end of a larger (and often video-first) piece of creative work, rather than an end unto itself. As a result, they’re handed to juniors late in the piece, and it shows.

2. Your search history haunts you

Google ads follow me round the internet, advertising a product I have already bought, for months afterwards. I bought some trousers from a shop in Wales last year. I love the trousers, but it’s been maddening seeing the poor shop continue to hammer me with ads for trousers I am literally wearing, for months afterwards. Or, in this example from the Daily Mail, an ad for a KiwiSaver provider I already use and a brain-drink I subscribed to yesterday.

“Retargeting is a really powerful tool, and the metrics show that,” says Brian. “But most people don’t think about the story arc.” To him, a more creative and successful approach would be to introduce narrative and storytelling beats there, which intensify the viewer’s feelings towards the brand, rather than hammering hard sells at every encounter. It’s the problem of what we measure, again.

3. Losing the story amid the ads

The NZ Herald’s Liam Dann is one of my favourite writers on the economy, because he writes clearly and succinctly in an area prone to jargon. He also has a habit of making each sentence its own paragraph, which is part of his methodical writing style. The only issue is that when placed online, the CMS makes it into a kind of bizarre avant garde poetry maze. Brian agrees that it’s a problem, but rightly points out that it’s as much about news organisations’ own UX and UI, which is placing boxes to prompt further reading or email signups between every paragraph, causing the chaos we see here.

4. The galaxy brain of the government being on Outbrain

“One of the measures of success for government agencies is how many people come to their website,” says Brian. “I have no idea why.” Me neither. Not just because expecting people to come to your website seems a somewhat quaint success measure in the social web era, but because Outbrain is a particularly strange place for the government to hang out.

As the late, great website The Awl pointed out in “A complete taxonomy of internet chum”, the strange, compelling ads that sit at the bottom of news stories are colloquially known as chum, and can be categorised into sub-varieties like “Sexy Thing, Old Person’s Face, Skin Thing, and Miracle Cure Thing”. These invariably lead to some of the sketchiest, scammiest places on the internet.

This is a very strange place for the government to be hanging out! The government is an increasingly large player in advertising, perhaps emboldened by the much-lauded and ubiquitous Covid-19 public health campaign. But while campaigns discouraging drink driving or smoking have a mass communication logic, Brian sees the MBIE ads below, which encourage digital invoicing (!), as somewhat futile – particularly given the scale of Xero’s always-on advertising campaigns. To be clear, MBIE are far from alone in this – you’ll see any number of government agencies and campaigns nested there. But so long as big advertisers support it with their business, news publishers will be forced to keep the lucrative but disgusting chumbox at the bottom of their stories.

5. A video you didn’t ask for plays right away

“The internet is rapidly videotising,” says Brian. This means that more and more of our time online is spent watching video, and because of that inherent bias toward video as a brand play online, news sites are desperate to create more video plays. That’s why almost every story now has a video attached, however tangentially related, and every time you fail to hit the pause button fast enough – boom, another impression sold.

It seems scarcely credible that those ads actually do the job assigned to them, but until we invent an acceptable format for brand ads within news stories, this is what we seem stuck with. It’s frustrating for us as a magazine site to feel like nothing has replaced the double-page spreads that were the hero ad format for magazines. But the mobile screen and modern attention span creates an awful pressure to create more video impressions, regardless of how much we all hate autoplay.

Is there a better way?

“Another metric actually changes the whole conversation,” says Brian. “I’m passionate about attention time.” This means that rather than counting the basics like views, impressions or clicks, we can start to get a sense of how long someone lingers on an ad. This is currently hard to measure outside of video, but there is fresh technology coming into view that might change all that.

“The part of the blockchain that really interests me is BATs – basic attention tokens,” he says. “Different ways of eliciting an involvement with a brand that is not predicated on the only thing that matters being a click.”

There’s a lot more coming everywhere in digital ads. Apple’s privacy changes made a US$10bn dent in Facebook’s ad revenue, while the so-called “cookiepocalypse” has many in publishing daring to dream of a different future. Cookies are behind a lot of this internet advertising hell – they’re the reason creepy ads follow you around the internet, based on your search history. Between changes to Google Chrome and new EU regulations, they’re likely to be less powerful in future.

Publishers are holding out hope of a return to context – wherein advertisers pay to be in a particular location based on who is likely to be there and what they’re likely to be into. The fact cookies follow you wherever you go has been the biggest reason premium locations like news sites are held to prices set at locations where advertising is not a core business. This is the true foundational reason why so many news sites the world over look like hell – and our best realistic shot at changing all that. In the meantime, the best shot at changing this dysfunctional mess is for those who control the money to demand better of the creative and its expression. It doesn’t seem like much to ask – but we’re decades into display and things seem stubbornly resistant to evolution.

duncan@thespinoff.co.nz

Follow Duncan Greive’s media podcast The Fold on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.