April 19, 2017: A range of viewpoints is a good thing. But giving a platform to noxious, hateful, racially inflammatory propaganda is quite another. So why is Newstalk ZB so keen on Katie Hopkins, asks Branko Marcetic.

Few would accuse Newstalk ZB of being a fountainhead for enlightened ideas. This is, after all, the radio station that lets Mike Hosking yell at the birds outside his window every weekday morning. But even so, you might think there would be some guests that are beyond the pale.

Apparently not. Over the last year, the station has become something of a second home for Katie Hopkins, a British television personality and columnist for the Daily Mail (previously The Sun) and attention-hungry troll who has proven unflinching in her readiness to bravely insult just about any marginalised group that exists. It’s not for nothing she’s been dubbed the “Most Hated Woman in Britain”.

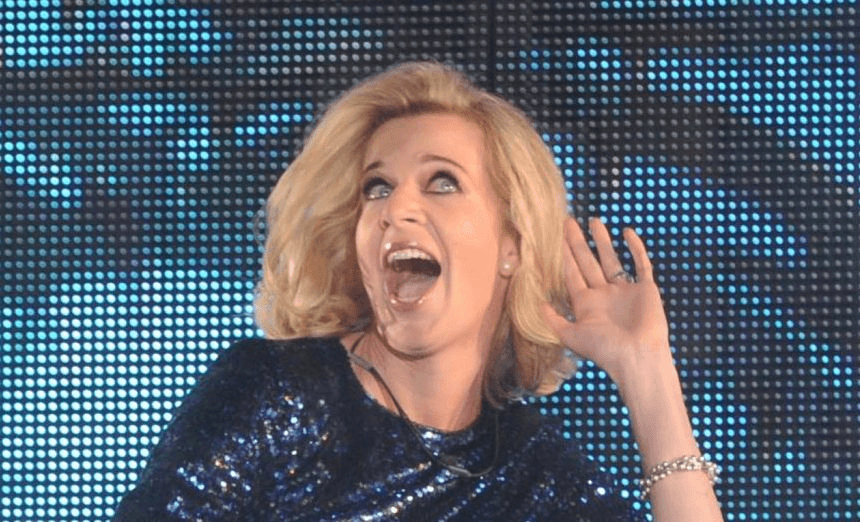

Hopkins has done well for herself, parlaying an appearance on the UK’s version of The Apprentice in 2007 into a regular BBC radio programme (and now a show on UK talkback radio station LBC), several newspaper columns, and more television appearances on shows like 8 out of 10 Cats, I’m a Celebrity…Get Me Out of Here!, Celebrity Big Brother and This Morning (roughly the UK equivalent of Good Morning).

All the while, she’s fashioned an image for herself as something akin to the Ann Coulter of Britain, a deliberately outrageous provocateur who aims to offend whoever she can, particularly the sensibilities of those who consider themselves liberals or anything further left. As Coulter and various shock jocks before Hopkins have found, drumming up outrage can be good business, particularly in an age when our keyboard trigger fingers are more sensitive than ever.

Suffice to say, listing every offensive thing Hopkins has said would take all day. A selection, however. She’s defended pre-judging children based on how “lower class” their names sound, made fun of transgender former boxing promoter Kellie Maloney’s horrific botched plastic surgery job, charged that being a mother isn’t a full-time job but a “biological status”, claimed she wouldn’t hire someone if they were overweight, charged that feminists want “special treatment” instead of equality, and she really, really doesn’t like people with red hair. There are whole video compilations on YouTube dedicated to her “bitchiest moments” and to seeing her get “owned” by various individuals.

But recently Hopkins has made the leap from eager pincushion for liberal rage to a genuinely influential bigot who uses her various public platforms to spread vile, race-baiting propaganda, particularly about Muslims and migrants of any non-Anglo stripe. Just days before hundreds of human beings drowned in a refugee ship in the Mediterranean, Hopkins wrote a column for The Sun calling for the use of “gunships to stop migrants”, referring to them as “a plague of feral humans” and comparing them to cockroaches. She claimed there were “swathes” of Britain where non-Muslims couldn’t show their face, then couldn’t name a single one of these alleged places.

She’s called Palestinians “filthy rodents burrowing beneath Israel” while urging for more bombing of Gaza, and referred to the sight of three-year old Syrian refugee Aylan Kurdi drowned on the beach as a “staged photo”. She falsely accused a Muslim family of being extremists with links to Al Qaeda, a charge that resulted in a libel suit that cost The Mail Online £150,000 and an apology, which Hopkins quietly posted at 2:07 am, a cunning strategy that might have worked better in 1998 than in 2016. This wasn’t Hopkins’ last libel suit. Last month, she was ordered to pay £24,000 in damages after falsely accusing food blogger Jack Monroe of vandalising a war memorial.

Her response to charges of racism? “I don’t care. [The term] has lost all meaning.”

In recent columns, she complained that the UK was “focussing effort and energy on Fat Joe from the darts club who was alleged to have left a pack of bacon from the Co-op outside a mosque, and not on borders and airports,” and explained that she can’t be Islamophobic because “a phobia is an irrational fear” and her “fear of Islam is entirely rational”. These are just a couple of the many apocalyptic columns Hopkins writes on a regular basis warning of the impending collapse of Western civilisation thanks to hordes of non-white and often Muslim migrants flooding over European borders.

And now she seems to have found a regular voice on New Zealand radio.

Hopkins has appeared on Newstalk ZB at least four times over the last year — likely more, given that her appearances aren’t all uploaded to the web. Each time she’s been treated as a credible source of information rather than the wide-eyed, race-baiting, inflammatory conspiracist she is. Like Louise Mensch and Piers Morgan, Hopkins has benefited from the apparently universal truth that all one needs to be taken seriously outside of the UK is a posh BBC accent.

In June last year, Hopkins appeared on Mike Hosking’s show in the wake of Brexit, where Hosking described her as “one of Great Britain’s more outspoken commentators”. The two stuck to the topic at hand, with Hosking picking Hopkins’ brain about the intricacies of British politics following the Brexit vote – is a recession coming? Who will be the next Conservative leader? What’s happening with Labour? – and, clearly charmed by her presence, laughing pleasantly at her description of the UK as “like a scene after a really messy wedding”.

Hosking didn’t bring up the fact that, leading up to the vote, Hopkins had written columns like this one, warning of a new “migrant invasion of Europe and destruction of our culture and values,” and doubling down on her description of migrants as cockroaches. Or that the day before the vote, she had written a column titled “If Remain win … I warn you not to expect a primary school place for your child, I warn you not to complain about the next terror attack.” Or that during this time, she had been championing Austria’s Freedom party, an organisation founded by literal Nazis.

But even that’s beside the point. One might wonder whether we would be so quick to let it go if Hosking invited an economist who had a history of peddling anti-Semitic nonsense to discuss unemployment figures, and described him as “a controversial economist?” Or if he yukked it up with a neo-Nazi film critic as they discussed the release of Suicide Squad?

In January this year, Hopkins was again back on ZB, this time to discuss Trump’s impending inauguration with Chris Lynch — fitting, given Lynch had earlier hosted Ann Coulter herself on his show. Hopkins was described as an “outspoken personality” this time.

Hopkins raved about the palpable excitement in Washington DC over Trump’s inauguration. “People out there selling the flags, the banners, the pins, the hats for tomorrow, and it’s really the feeling of a city that’s just waiting to burst into action tomorrow,” she told Lynch.

Hopkins turned out to be absolutely right, of course: DC was ready to burst, except not so much for Trump’s inauguration, which was famously and embarrassingly under-attended, but in advance of the anti-Trump Women’s March in Washington, which blew the inauguration attendance out of the water. Hopkins’ intrepid on-the-ground reporting had somehow failed to pick up on this.

Nevertheless, she made sure to denigrate the Women’s March as “a million women who don’t really have a point, but just see themselves as victims”, and complained that while it was people like her who were “blamed for hate crimes”, it was “the Left, the Democrats, the liberals who seem full of hate”.

The low point of Hopkins’ adventures on ZB, however, was her March appearance on Larry Williams Drive to talk about her recent trip to the hellish, war-torn land of Sweden. Hopkins’ appearance came shortly after Trump had appeared to reference a non-existent terror attack in Sweden; Hopkins’ experience in the country was presumably meant to serve as the corrective to media criticism of Trump’s fabrication.

Let’s put that into perspective: Hopkins — who has repeatedly peddled nonsense in order to demonise ordinary Muslims, and who completely misread the mood in DC while she was physically there — was serving as Newstalk ZB’s eyes and ears on the ground in Sweden.

Hopkins’ “reporting” built on the same themes she had outlined in a couple of columns about her trip, in which she had painted the country as a lawless cesspit overrun by migrants, where police don’t dare to tread and “hand-grenade attacks are the accepted norm”. Hopkins had already appeared on Fox to defend Trump’s words and explain her findings, and her columns had been picked up by far right websites like Infowars.

Williams opened by asking Hopkins if the problem with “immigrants and crime” in the country was as bad as Trump made it out to be.

“It’s bad,” replied Hopkins.

She chose some curious examples to illustrate this point. She referenced a suspected arson of an asylum centre and a hand grenade placed outside of a mosque — which, if true, suggests the perpetrators of these crimes weren’t immigrants, but rather those opposed to immigrants.

“There are areas where I’ve been spending time in where I am the only white woman, I am the only woman out after about 8 o’clock at night,” she warned, “and certainly the entire population is made up of Muslims … and all hailing from Afghanistan, Syria and those sorts of countries.”

“The white people have been pushed out, and the place is now overtaken by people who don’t even speak — they certainly don’t speak Swedish, they speak Arabic,” she continued.

“And that’s what we now face here in Sweden,” she concluded, forgetting that she was British.

Williams then asked if there was “concrete evidence that crime in Sweden is on the rise”, before alleging that the Swedish government was purposefully not releasing its crime statistics.

“They won’t release them, that’s correct,” said Hopkins.

The idea that the Swedish government was hiding its crime statistics as some sort of cover-up of the truth of the perils of immigration is a popular one in fringe right wing circles, but one that is entirely untrue. In fact, the Swedish government had released the crime statistics for 2016 just over a month before Hopkins sat down with Williams. Meanwhile, even a quick glance at the publicly available Swedish crime statistics between 2005 and 2015 shows that the numbers have stayed steady over the decade.

Hopkins continued to spin more fantastical stories. “In areas of Sweden, there’s more hand grenades that detonate than some major war zones”; a story of one woman’s mortal fear that the “Swedish feminists would come and get her” if they found out she had spoken out against Muslims; bridges being replaced so that police can see if migrants are standing on top of them waiting to stone emergency service vehicles.

“I don’t have an agenda,” she said. “I’m just here as a normal woman, surprised and shocked by what I’ve seen.”

All of this was allowed to pass unchallenged by Williams, despite Hopkins’ well-documented record of fabrication.

And it has continued. Just this week, Hopkins re-appeared on Chris Lynch’s breakfast show to talk about the wisdom — or lack thereof — of Trump’s decision to involve the United States more deeply in Syria, and the conditions in Sweden in the wake of last week’s attack in Stockholm.

Given her non-interventionist stance, the first part of the segment was probably Hopkins at her most lucid, correctly alluding to the dangers of deposing Assad without having a clear plan in place and pointing out the dangers of leaving a power vacuum in Syria. The same can’t be said for the second half.

Once again, Hopkins shared her terrifying tales of being “surrounded by men from Somalia and Eritrea,” and of the vast liberal conspiracy suppressing the truth about how far Sweden had degenerated (in Hopkins’ world, Sweden is at once a place that is indistinguishable from a war zone, and somewhere she can casually walk around alone in even the most dangerous neighbourhoods).

For Hopkins (and presumably Lynch, given he didn’t utter a peep during Hopkins’ assertions), the recent attack by an ISIS sympathiser who was being deported from the country was a symbol and symptom of the failure of liberal policies, not just in Sweden but in the West more generally. She went further, complaining that the “lenses of the mainstream media are are focused on the victims of migration” while neglecting “the victims of terror”, alleging that while the photo of drowned three-year old Aylan Kurdi had been plastered anywhere, barely anyone hears about the Western victims of terror.

“We spend a lot of time … sitting on a mounting pile of dead bodies of the victims of terror in order to get one good picture of the victim of migration,” she concluded.

“Always great to have you on the programme,” replied Lynch.

What you wouldn’t know from Hopkins’ narrative is that, despite her alarm over the perils of Islam and over scary dark-skinned men taking over once white neighbourhoods, the Stockholm attacker was from Uzbekistan and reportedly wasn’t particularly religious. You also won’t hear about men like Abdi Dahir, a Muslim taxi driver originally from Somalia who was attacked in his taxi hours after the Stockholm attack. That’s because these are the stories and facts that are subsumed by the wall-to-wall news coverage terrorist attacks in the West regularly receive.

Neither does Hopkins ever mention the white, Christian, Norwegian terrorist Anders Breivik, who still has the record for committing the worst terror attack in Scandinavia when he killed 77 people in 2011. The most she has written about Breivik is to call him a “mass murderer” in a tweet where he was the punchline to a joke making fun of five recently drowned London men. After all, this was the same woman who stressed that the racist, “Britain first”-shouting man who killed British MP Jo Cox in the midst of the Brexit campaign “had a history of mental illness” and a “troubled mind.” Terrorism is only terrorism when the perpetrators aren’t white.

But being angry at Hopkins is beside the point. Hopkins knows what she’s doing. She knows that attacks in the West monopolise media attention. She knows the Swedish crime statistics are perfectly easy to get a hold of. She knows all this just as she knows that judging little children on the names their parents give them is a ridiculous thing to do.

Hopkins’ turn to outright race-based conspiracising is just an extension of her early-career trolling, part of her quest of following that which will give her the most public exposure and money. According to Hopkins, she was paid somewhere in the neighbourhood of £400,000 for her Celebrity Big Brother appearance in 2015. She now has a book deal. Just as Coulter and, more recently, Milo Yiannopoulos have found, if you play your cards right, you can ride a wave of popular outrage to notoriety and riches in the modern world.

We’ll always have desperate attention-seekers like Hopkins. And we are all better for hearing a range of viewpoints, including and especially those we don’t agree with. But none of that should extend to providing a platform for noxious, hateful, inflammatory propaganda. I can’t believe I’m writing this, but Newstalk ZB is better than this.