The political supergroup’s event about Wellington’s art scene involved lots of CEOs and very few artists.

Windbag is The Spinoff’s Wellington issues column, written by Wellington editor Joel MacManus. Subscribe to the Windbag newsletter to receive columns early.

I’ve been pretty sceptical about Vision for Wellington, the supergroup of wealthy and powerful Wellingtonians, ever since it launched with a glowing front page story in The Post. They’ve made absurd claims that their inherently political project is “non-political”. Sinead Boucher seems to have used Stuff as the group’s internal marketing department. Their star-studded debut event was devoid of vision and consisted mostly of angry retirees complaining about bike lanes.

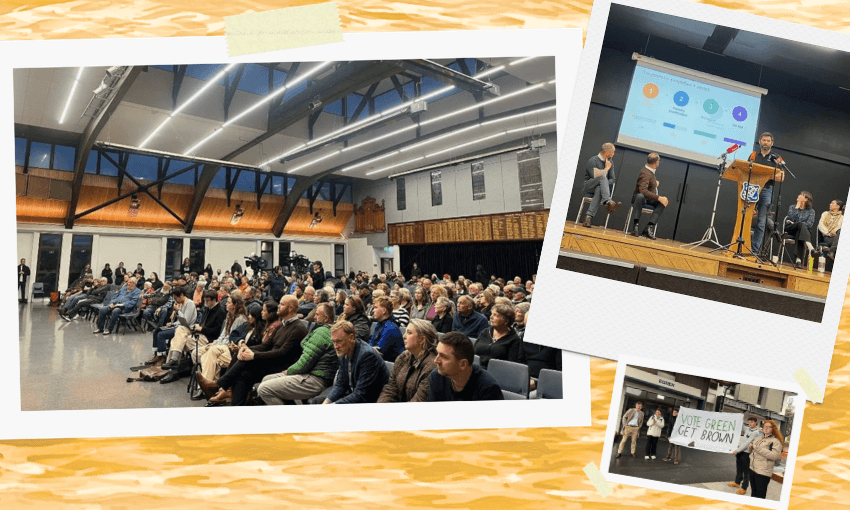

Credit where credit’s due: the group’s second event was more interesting and constructive than the first (though that’s not saying much). “A Creative Conversation”, focused on Wellington’s art scene, was held on Thursday last week at Toi Whakaari in Newtown. It ran for nearly two-and-a-half hours, starting with a panel discussion followed by an audience brainstorming exercise. Throughout the evening, two people frantically jotted notes on whiteboards; Vision for Wellington has hired consulting firm PwC to collate its ideas and write its final “vision”.

The three panellists were impressive. Muralist and sculptor Ariki Whakataka Brightwell presented some of her pieces and discussed the challenges of finding workshop spaces. NZ Art Show director Carla Russell highlighted the importance of finding profitable models and working with the business sector. Wētā Workshop founder Richard Taylor brought out the Wētābot005, a Terminator-esque robot that was both awe-inspiring and terrifying. It remained on stage for most of the event, subtly lifting its arms and chest every few seconds as if it were breathing.

The audience was considerably smaller than the 1,000-strong crowd at the first event, with the 200-seat theatre about three-quarters full. Most of the audience members were individually invited because the group deemed them “important members of Wellington’s arts and creative community”.

When MC Simon Bowden asked how many of the audience were artists, about 10% raised their hands. When he asked how many had a second job to support their art, the number halved. There were plenty of chief executives and board directors who run arts organisations, but very few people who make art.

At the start of the brainstorming session, Bowden invited six early-career artists (the youngest people in the room by far) on stage to ask “provocations” for the crowd to discuss. The results were a mixed bag. The crowd suggested a council-funded role to help artists with administrative tasks, a city arts hub, and an artists-in-residency programme within government ministries.

One person raved about their recent visit to the British Museum and suggested, “What we really need is a museum that incorporates our music and our art” (a fascinating idea for the city Te Papa is in). Carolyn Henwood, a founding member of Circa Theatre, wanted to create a unified arts industry group in the vein of Beef + Lamb New Zealand or New Zealand Winegrowers. Richard Taylor suggested forming a commercial board to be “the Fonterra or Zespri of the arts world”.

When you put a bunch of board directors in a room to solve a problem, it’s not surprising that their idea is to create another corporate board. When all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. This is the fundamental problem with the Vision for Wellington project so far. They’re the upper class, talking to the upper class. The people who will take Wellington’s art scene forward aren’t sitting in board meetings. They’re putting on grimy gigs at Valhalla and unhinged shows at BATS. They’re 21-year-old buskers, not 65-year-old CEOs.

Let’s ask the question no one at the Vision for Wellington event asked: what makes a city’s art scene great?

In 2022, researchers at Columbia University tried to answer that question with a study titled Towards quantifying the strength of music scenes using live event data. They used the number of live music shows per 100,000 people as a rough indicator to measure the strength of a local music scene. Then, they explored how it correlated with 28 socio-economic indicators.

The factors most strongly correlated with thriving music scenes included the number of performance spaces available, affordable rents, high population density of people aged 18-29, and high rates of public transit use, cycling and walking.

If up-and-coming artists are surrounded by their peers, have plenty of opportunities to perform, and can afford to survive with a part-time job, they have the best chance to develop their talent.

In the late 90s and early 2000s, Wellington produced an enormous number of breakthrough artists (Taika Waititi, Jemaine Clement, Bret McKenzie, The Phoenix Foundation, Fat Freddy’s Drop, The Black Seeds, Fly My Pretties, Fur Patrol, Dai Henwood and Jo Randerson, to name a few). That’s because the growth conditions were ideal. There were twice as many performance venues operating, and rent was a hell of a lot cheaper.

In 2025, there are still plenty of cool people making interesting art (shoutout Dartz, Dateline and Maria Williams) but they’re doing it in an environment that makes it much harder to succeed.

Richard Taylor spoke about live music as the nucleus of the art scene. “Youth culture gathers around the brightest lights,” he said. Young artists “deserve a home”, but Taylor said he was worried about the financial pressures they faced. He gets it. I’m not sure anyone else from Vision for Wellington does.

When an audience member made an impassioned plea for affordable housing – “If people can’t afford to live in the city, that’s the issue” – there was an awkward silence. Then, a couple of people started clapping (I joined in). Bowden hurriedly cut off the applause and moved on, insisting they were behind schedule and didn’t have time to dwell on housing. The event ran for another 75 minutes after that.

Maybe Bowden was worried that housing was too political. But these are political problems. Successive councils have created a housing shortage by introducing zoning changes that restricted the construction of new homes. They’ve made it more difficult for venues to operate by limiting opening hours and liquor licensing and cracking down on noise complaints.

Vision for Wellington, so far, has been unwilling or unable to grapple with the role the cost of living crisis plays in Wellington’s malaise. I suspect that’s because they don’t feel it.

Here’s my practical suggestion for Vision for Wellington: go talk to the E tū Musicians’ Union about its successful efforts to change the council’s noise control rules for venues. Find out what else they need and use your power to amplify their voices.

Then, go talk to A City for People, the young-people-led Yimby group that spearheaded the fight for zoning reform to allow more housing. Use your considerable wealth and influence to support property developers who want to build homes and oppose those who try to stop them. It would do a lot more good than another two-and-a-half-hour talkfest in a room full of CEOs.