Audio description comes as standard on shows streaming on Netflix and other international services. So why are TVNZ+ and ThreeNow still lagging behind?

I have lived with a disability for more than half my life. During that time, I’ve met a lot of people who live with different disabilities, and I have heard a lot of their stories. The very recent history of how people who live with disability have been treated in New Zealand can be harrowing at times.

We have a representative from the blind community on our board of trustees for Able, the charitable trust I have the privilege of working for. Now in his sixties, he recently told us a story about being at school and, due to having a small amount of sight, being forced to go up close to the blackboard to try and read the teacher’s chalk scribblings. As he shuffled side to side, trying to navigate his way through the chalk dust, his face centimetres away from the blackboard, students would throw things at his back.

So while I’ve heard – and experienced for myself – a spectrum of the good and the bad, I find disability fascinating. What visualisations make up someone’s dreams when they are blind? What does a human voice sound like for someone who uses a cochlear implant for the first time, and does music have the same resonance?

You probably have questions about disability yourself. If you’ve ever wondered whether blind people watch TV, the answer is simply: yes.

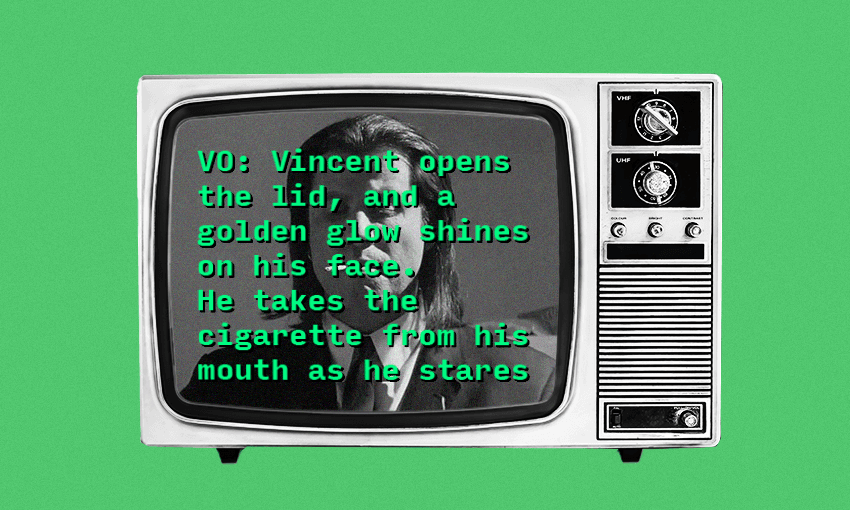

Audio description is something I have always found best experienced rather than explained, and the scene from Pulp Fiction below is one of my favourite audio description clips to point people towards. If you are sighted, I recommend listening without watching the screen to understand how rich audio description can be. It demonstrates perfectly what audio description is: an alternate audio track that describes what is visually happening on screen, mixed in with music, dialogue and effects.

I’ve known about audio description for a long time, but when I decided to apply for my current role as chief executive of Able, I did a deep dive into the world of making media accessible. As part of my research, a friend who is blind talked to me with great passion about what audio description means for her. She had always enjoyed David Attenborough documentaries but said she had no idea what she was missing until she was able to watch them with audio description. It was then that the world contained in those documentaries came alive.

Audio description is a fantastic development. It’s an added value to the many great shows we’re so lucky to have available to us on streaming in 2024.

But imagine not being able to watch the latest season of Taskmaster NZ, or the recently acclaimed New Zealand drama After the Party whenever you wanted? Imagine having to schedule it in your diary – “appointment viewing” as they say, like it was still 2003?

For people in New Zealand who rely on audio description, that’s their reality.

Thanks to funding from NZ On Air, Able provides audio description for shows and movies to our free-to-air broadcasters, but these are only made available on TVNZ 1, TVNZ 2, Three and Duke (but not on Sky Open, as it doesn’t currently have AD capability) because the streaming services TVNZ+ and ThreeNow aren’t able to host audio description.

That means people who are blind and want to watch NZ On Air-funded shows must do so via broadcast television – at the specific time the show is airing, and only then. That sounds extremely inconvenient.

While the big international streamers (Netflix, Disney+, Apple TV and the like) have got it (mostly) sussed when it comes to making their content accessible, New Zealand broadcast on-demand platforms are simply not there. The future is not now; we’re barely living in the present.

To be fair, unlike our local broadcasters, international streamers have very deep pockets. But if money is part of the conversation, and it usually is, we can surmise that the international services aren’t providing audio description for purely altruistic reasons; leading with universal design means they can deliver an offering for every potential paying subscriber they can get their hands on.

New Zealand alone has 220,000+ people who are blind or visually impaired and who would benefit from using audio description, and this year’s NZ On Air research survey, Where are the audiences?, showed that almost 10% of people surveyed watched content using audio description. Extrapolated to the population of New Zealand, and with a conservative estimate, that’s over 450,000 people – more than double the number of people who identify as blind or visually impaired. There’s an adage common in accessibility sector: when you design for the few, you make things better for everyone.

We can acknowledge people who work for Aotearoa’s broadcasters are good people doing good work, and we can acknowledge they are often busy people working within difficult constraints, including money and time. But we can also expect them to care and deliver for all New Zealanders. All of these things can happen simultaneously.

So, where do we go from here?

While there’s still no magic formula for retaining local audiences, ensuring that screen content is accessible on the platforms where the audiences are (or are at least moving to) is bread-and-butter work that is currently being sidelined, to the point where it seems that to bring our local streaming services up to speed may require legislation.

Many comparable countries, including Australia, the UK, Canada and the US, have long required captioning or audio description on their television programmes.

With a new broadcasting and media minister – one who has a background in addressing the needs of underserved TV audiences – and the 1989 Broadcasting Act ready for an overhaul, this may be our opportunity to enshrine screen accessibility into law.

The disability community wants change – specifically, we want local content to be available and accessible where people are watching content: on TVNZ+ and ThreeNow. If change doesn’t happen, New Zealand audiences will continue to turn away from our local offerings, contributing to the flow-on effect of a loss of the localisation of language and culture in the media we consume.

This issue isn’t complicated; it’s simply the right thing to do. Yes, blind people watch TV. And they deserve to be able to binge-watch every episode of their latest guilty pleasure until three in the morning, just like you do.