When communities say no to bottle stores, why are licences still being granted? A new study finds out.

When a bottle store applied for a licence next to a Māngere school, Hone Fowler wanted to do something. The South Auckland resident, who has been the manager of a community centre and worked extensively with local sports clubs, was running a youth group at the time. Thinking of the young people he worked with having to walk past an alcohol store each day made him desperate to object to the licence. “Alcohol being sold at the doorstep of the school – that shouldn’t be seen as normal,” he says.

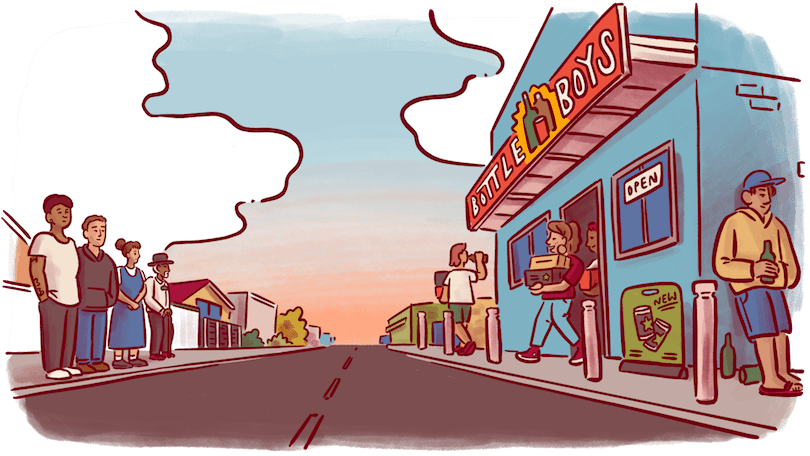

But all too often, it is. Low-income areas in Aotearoa have a much higher density of alcohol stores – and therefore, the related harm that comes with them. A new study conducted by Massey University’s SHORE & Whariki Research Centre tracked some of the harms that trouble local residents, and what happens when they raise their concerns with licensing authorities. The research team interviewed people in eight communities across Aotearoa, predominantly in low-income neighbourhoods, including where communities objected to an alcohol licence but weren’t successful.

“We know from national surveys that noise, broken glass and avoiding drunk people are the most common impacts of alcohol on people other than the drinker,” says Marta Rychert, a public health law researcher at SHORE & Whariki who worked on the study. “The people in residential neighbourhoods saw these issues too – alcohol impacted how much they can enjoy where they live and where they go.”

The harm has subtle flow-on effects: public drinking makes some parents anxious about their kids walking to school, so they drive instead. This means that they miss out on the positive social and physical implications of a walkable neighbourhood.

Fowler gives another example: the area where the football club he volunteers with meets to practise is also a popular drinking spot. On Saturday mornings, the field sparkles with broken glass – which isn’t safe for people who just want to play sport. “It reduces the likelihood that those young people and families will come back to those spaces, so they miss out on staying healthy and active,” he says.

While some people weren’t as affected by the alcohol harm around local bottle stores, the SHORE & Whariki team found that people in six of the eight neighbourhoods they studied thought there were too many bottle stores. That availability is in part a product of how alcohol licensing decisions are made.

Theoretically, community members have the ability to object to new alcohol licences and licence renewals at the district licensing committee. At hearings, the committee listens to community objectors, the applicant seeking the licence and public officials in alcohol roles.

In practice, however, community members feel that this process is heavily weighted in favour of the applicant, with the committees not equipped to hear community concerns. “I feel angry, and I feel sad,” says Fowler, who has been demoralised by six years of sitting through hearing processes without a positive result. “I’ve seen people brought to tears, I’ve seen people cross-examined over and over unnecessarily, I’ve seen people told they can’t speak te reo Māori – going through these disempowering experiences puts people off from engaging with the [licensing] process.”

The study affirms that Fowler is not alone in this experience. “The process is very legalistic, with quite formal protocol,” says Rychert. The research team found objectors often couldn’t afford a lawyer, for instance. “Many of these communities aren’t well resourced to engage with the process and to gather the specific type of evidence the committees want.”

If a community member wants their voice to be heard about an alcohol licence, they usually have to take time off work, as hearings are held during the day. They walk into a room with an applicant who has an experienced lawyer and a business case. The burden of proof is on community members to show there is a risk of harm related to that alcohol store, rather than alcohol in general. The panel listening usually have legal or business backgrounds – not expertise in health, science, or te ao Māori.

“The process isn’t community-friendly,” says Rychert, “yet the residents we interviewed knew about common and relevant risks that were not covered in the recorded offences or injury data that public officials usually provide. And if that official data is lacking, community objectors’ evidence is questioned more deeply and often passed over.”

The effect of this is to magnify the inequity that harm from alcohol already produces. “We need new frameworks that uphold the mana of our communities and Te Tiriti,” says Fowler. He’s stopped engaging with district licensing processes because “it was a time and financial burden” where communities never got what they were asking for. Where he did see results, though, was in objecting to bottle store applicants individually – in one case, he managed to convince a fruit and vege shop owner not to start selling alcohol by asking directly. “We all want a healthy community, we all want businesses to succeed and our people to thrive – and you don’t need to sell alcohol to do that.”

While changes are slow, both Rychert and Fowler hope that improving the process for engaging with licensing will lead to better outcomes for communities in Aotearoa. “The system isn’t fit for purpose,” Fowler says. “There needs to be a revision of the Act to rebalance it in favour of communities – their aspirations, dreams, and wellbeing.”