Recognising that mental health is affected by the environment we live means we can focus on getting the fence built at the top of the cliff rather than the therapist at the bottom, writes Olivia Wills.

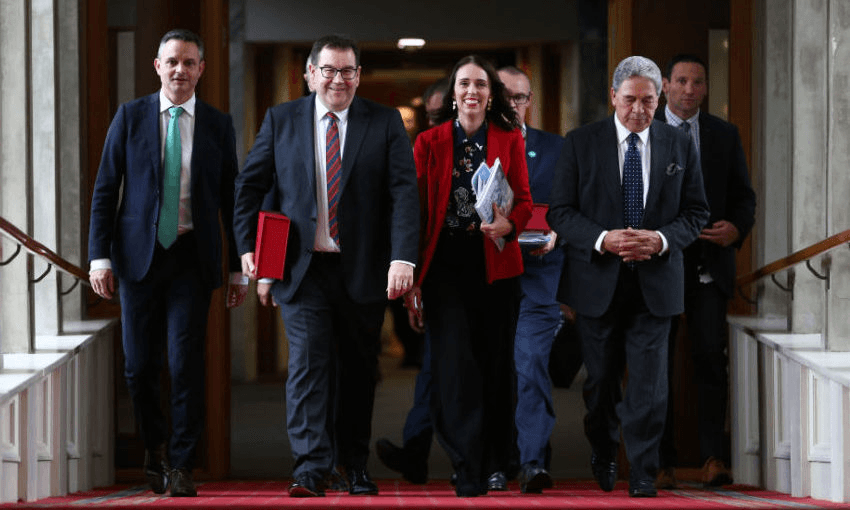

The build-up to the world-first “wellbeing” budget was anything but dull. With documents leaked and a hack which was not a hack at all, it’s been a busy week at the Beehive. The 2019 budget was touted by Labour as the first to go beyond economic growth, instead focusing on improving lives. But National said that a wellbeing focus is nothing new, it’s what they were doing all along. At last the wait is over, and we can answer the question – when your budget explicitly focuses on wellbeing, does anything actually change?

On the face of it, yes. The headline statistics are certainly about improving lives; there’s $1.9bn for mental health services, including $455m to get 325,000 people access to mental health services. The package also includes increases in the number of transitional housing placements. That’s not traditionally a mental health issue but all the evidence suggests it’s a big factor. Recognising that mental health is affected by the environment we live in is a notable step in the right direction; it’s far more effective to get the fence built at the top of the cliff than put a therapist at the bottom.

The government is proud of its integrated approach; aim for improved outcomes and cut down the internal squabbling over funds. Mental wellbeing is indirectly affected by most parts of the budget. When the best long-term determinant of mental health is attachment to a caregiver in the first three years of life, the most effective way to prevent mental health problems is to make sure parents are supported. Parents who are burdened by the necessity of working long hours, or who have mental health issues themselves, can be at risk of passing on the problem to future generations. That’s why this budgets’ biggest steps towards improving mental health long term aren’t in the package at all; firstly, an extra $80 million for Whānau Ora, a scheme which allows the whānau to state what’s needed to improve outcomes, and secondly indexing welfare payments to wages, which in a few years’ time will see substantial increases in money for those who need it.

At the same time, climate and mental health are also linked, and announcements on global heating are much quieter and not proportional to the climate emergency we face. While “natural capital” is one of the pillars identified for wellbeing, in reality it’s very difficult to measure, which may have caused it to slip under the radar.

Are the changes enough?

The mental health inquiry, which the government largely accepted this week, brings to light dire statistics on the mental health of New Zealanders, and makes the case for urgent reform. One of the 38 recommendations is to get secondary mental health services accessible to 20% of the population – that number is currently 3%.

Noticeable progress is going to take time, and it’s important we don’t judge the outcomes too soon. When you try to ramp up the scale of mental health services by several times the current size, there’s going to be some time-consuming problems. Clinical psychologists, nurses, social workers and other professionals need to be trained, a long-term undertaking. Group and online therapy need to be expanded and rolled out. Increasing access to services is just the start; there’s no quick fix for mental health and those who are helped by the system are undertaking a long-term process. The good news is, if we are currently treating the bottom 3%, the cost-per-person is going to decrease as we move up to 20%, as the resources needed become less intense.

So is there anything special about a wellbeing budget?

While the budget is unique in its headlines, it’s mostly business as usual. After paying for all the bulky must-haves; education, health and social security, there isn’t heaps of room for manoeuvre, so the world-first budget was always going to be a little underwhelming. Maybe previous governments had been using their budgets to improve the lives for New Zealanders after all and forgot to call it “Wellbeing” – the closest we got was “Social Investment”. But that’s not to say the wellbeing label is meaningless. Language is important, and changing the way we talk about the economy, from an entity which must grow money to one which exists for our wellbeing is significant progress.