Outside the arcane world of tax havens few had noticed Mossack Fonseca creeping into the South Pacific, but New Zealand journalist Michael Field was one. He recalls how he confronted the co-founder of the law firm at the centre of the Panama Papers data leak.

Jürgen Mossack came to Auckland to shut me up.

For a moment it felt like a war movie cliché. Steely eyed and ramrod straight, Mossack could have clicked his heels just as his German Waffen-SS father had.

It was March 2000 and the 52-year-old co-founder of Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca had already threatened me with legal execution in the form of a libel writ. In a rent-an-office space in Hobson Street, across the road from the Auckland District Court, he wanted a halt to my stories on his firm’s operations in Niue.

Instead, by chance, I got one of the few media interviews he ever gave. I asked him whether his Niue tax haven operation was morally right. He thought a moment and replied: “There is a big grey zone, there is no clear cut area.”

*

I’ve spent pretty much all my journalistic life writing about the Pacific. It’s been a treasure, a source of such unusual people and such great stories – why would you not want to cover it?

For a time, I worked as press secretary to Samoa Prime Minister Tupuola Efi (now Head of State Tupua Tamasese Efi). I got to meet many of the founding members of the independent Pacific, including the colourful Cook’s Premier Albert Henry and Nauru’s scary President Hammer deRoburt. I could see that Pacific leaders were all vulnerable to money-making suggestions, if only because they had so little cash. Carpetbaggers queued up in political waiting rooms.

Later, as Pacific correspondent for Agence France-Presse (AFP), I could see which conmen and dubious opportunists had got their feet in the door. A number of them wore sharp suits and stayed in top hotel rooms; the Mossacks of the world.

The Cook Islands were first up, a complex tax scheme which would gain fame in New Zealand as part of Winston Peter’s “winebox” saga. Because it was directed at Australian and New Zealand tax avoidance, it was well reported here.

Reporting on Nauru and its corrupt president Bernard Dowiyogo proved a drawn out and fraught affair (with threats of physical injury, including one by a senior Nauru official when we were both onboard an RNZAF Boeing 727 heading to a Pacific Forum). With phosphate money running out, Nauru was a wild west tax haven; 450 banks were registered to a single Nauru mailbox. It turned out, as I and other AFP colleagues discovered, to be a money laundering front. Victor Melnikov, deputy chairman of the Russian Central Bank, claimed in 1999 over US$70 billion of Russian mafia money had been laundered via Nauru (the actual money was in accounts in the Bank of New York).

Various diplomats leaked information about the accounts. Nauru has no friends in the world, just countries that use it. Through the leaks I found out that around a third of the 450 “banks” were of Middle Eastern origin, including Al-Qaeda fronts. The same names turned up again a few years later, when Tonga instituted a flag of convenience shipping scheme.

Nauru paid the price following the 9/11 attacks. Dowiyogo was ill – in a country with among the world’s sickest people and a low life expectancy, not too surprising. The US government offered to fly him to the States for heart surgery. While in his sick bed, State Department officials successfully pressured him to close down the tax haven operation.

Dowiyogo then died there in bed. A US official eulogised him: he had “truly died in the line of duty”.

I always thought that would make a great little movie.

*

Other scams were running out of places like Samoa and the Solomons. There were “letters of guarantee”, or LOGS, and “prime notes”, essentially meaningless Ponzi-type investments – outlawed nearly everywhere – that made vague promises of high return. Usually they were sold as a mortgage on the billions of dollars of manganese nodules nobody had yet worked out how to get off the Pacific Ocean seabed.

Some of it was ridiculous, like the time Tonga nearly signed over citizenship and land to a South Korean scam which claimed it could turn seawater into natural gas (Tongans were told their seawater was better than anybody else). I was leaked paperwork and discovered it was a trick to get access to an atoll to store nuclear waste. Some of the Tongan royal family were to have benefited from it. The entire crazy story is detailed in my 2010 book Swimming with Sharks: Tales from the South Pacific Frontline (Penguin).

Various forms of tax haven banking were springing up, in Vanuatu, the Cooks and, more recently, Samoa.

I always found it hypocritical that many of their leaders, always big on espousing Christianity, were apparently keen to climb into malfeasance and sometimes blatant criminality. They would justify it by saying places like Hong Kong and Delaware were doing it. There were no victims, they would say.

But these nations expected and accepted that they would get millions in aid from Australia and New Zealand. While they depended on the aid, they were also going around the back to help rob the very taxpayers funding that aid.

*

This poisonous atmosphere must have seemed fertile ground for Jürgen Mossack.

He told me that he had never heard of Niue but had wanted a location outside the Caribbean and in an Asia-Pacific time zone. They wanted it to be part of the Commonwealth with no scandal attached.

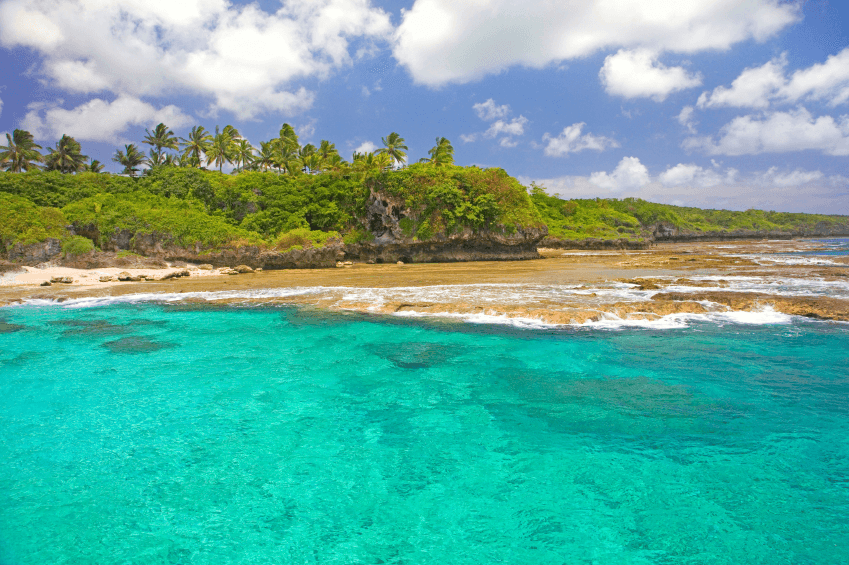

His competitors already had the Cooks and Vanuatu, but Mossack discovered – like James Cook before him – the island of Niue.

Niue sold itself cheaply, just $150 per year for each newly registered company, but the truth was the Panamanians made it known there were other options – and nobody was offering Niue that kind of money.

“We figured that if we had the exclusivity we would avoid the price wars because in off-shore jurisdictions there is a lot of competition going on,” Mossack said.

At the time Mossack was hunting, Niue was run by one-time merchant seaman Frank Lui. He thought the exclusive 20-year-old deal was an improvement on another small earner in Niue – renting out its telephone numbers for sex-lines in Europe. Lui lost his post in 1999, to be replaced by ex-New Zealand Army corporal Sani Lakatani. For much of his time as leader of Niue, Lakatani was living in Auckland and collecting national super. He still is.

Niue had seemed an odd choice for Mossack at the time, as the only air access was by once-weekly flight provided by the flakey and now defunct Royal Tongan Airlines.

Mossack said that was an advantage to those wanting to protect their secrecy. In an era of the Panama Papers that is deeply ironic; I look forward to reading the Niue Papers.

The deal saw Niue make $150 for every “international business company” (IBC) set up in the country. Eventually 6000 accounts were set up, earning Niue around $1 million a year.

Mossack Fonseca appointed a local agent to look after the files. Her name was Peleni Talagi. Her father, Toke Talagi, is now Prime Minister of Niue.

On their web page (now long gone) Mossack Fonseca described the advantages of Niue as “total secrecy and anonymity”. There were no requirements to disclose beneficial owners, nor any need to to file annual returns. “Complete business privacy and confidentiality” was assured.

Helpfully, Niue allowed company creation in Chinese characters as well as Cyrillic or Russian script.

Like others, I was noticing the explosive growth of Niue against the mature regimes in the other havens. I would write the occasional story on Niue’s economic success for an international audience. Jürgen Mossack was reading them.

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand and Treasury were moving out of a period of benign neglect toward Niue and the heat was going on John Hayes, head of the Pacific desk at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The government feared that Mossack Fonseca’s Niue operation was a threat to the New Zealand dollar. Hayes would fly up the country to see the Niue prime minister in his Auckland home. Lakatani refused to close the operation down.

I knew Hayes well. He had been negotiating a truce in Papua New Guinea’s horrible Bougainville civil war. It had been a dangerous job, and Hayes had at one point been shot by rebels. He was ultimately successful in ending the war.

Later he became the National Party member of parliament for Wairarapa. In 2009 he spoke during the debate on the Anti-Money Laundering and Countering Financing of Terrorism Bill.

“(It) was very easy to set up a company in Niue, for example, with an 0900 number, and talk to a hot voice or something, in a recording,” he said. “A call could be made on a Friday afternoon and the phone left off the hook until Monday morning. The caller would invoice himself or herself via the company in Niue, send the cheque to Niue, and launder the money that way.”

Big players like the Group of Seven, the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the Financial Action Task Force and the US State Department were starting to express alarm. My bosses in Hong Kong were interested in more, especially when the US State Department’s International Narcotics Control Strategy Report said, “Niue’s thriving offshore financial sector has been linked with the laundering of criminal proceeds from Russia and South America.”

*

My reporting and Hayes’ nagging was irritating Mossack Fonseca, who sent the inevitable threatening legal letters to AFP. Jürgen Mossack headed to New Zealand.

His first priority was to close down Hayes. Mossack demanded a meeting with then Foreign Minister Phil Goff, who refused to meet him.

I agreed to meet, but only on the condition that everything was on the record.

Being a sole correspondent in New Zealand was usually an advantage, but for a meeting with a man I knew to be a tough character, I felt the need for some company.

Radio New Zealand’s Pacific Correspondent Barbara Dreaver (now with TVNZ) was an old friend and, as an ex-Cook Island journo, she knew something about tax haven operations.

She recently summed up the basics of our meeting in a tweet: “He was angry and intimidating didn’t like us much.”

Mossack plainly wanted the high ground in the interview but seemed to have little media experience. He talked too much for somebody who believed he was right.

He denied his Niue operation was laundering “criminal receipts”. His business involved people “trying to avoid paying taxes in their home countries” – crucially “avoidance”, “unlike evasion”, is within the law.

The OECD was using money laundering as a pretense to go after tax, he said. Niue had been offering “unfair tax competition” to the OECD.

That was laughable.

He suggested the rich should protect their tax base in their own countries, not by beating up Niue.

“If OECD countries want to be serious about unfair tax competition they are going to have to close down their own operations first.”

He made several fair points, notably about the nature of money laundering. He pointed out that even in places like Nauru it could only be done with the aid of the world’s big banks. A decade later, covering New Zealand’s shell company operations, I could see that Mossack was right.

Vast amounts of Mexican drug money was laundered within the United States by banks like HSBC – using New Zealand shell company fronts, mostly set up by father and son operation Geoffrey and Michael Taylor, whom I later exposed.

“Every operation of that scale needs the intervention of the big international banks,” said Mossack. “When they see an unusual operation they must know it, and if they then continue the business it is because either they are not interested in the morals of the story, or they see it as good business to continue these operations.”

“If you have figures of that sort… then the international banks know what they are doing.”

Perhaps he realised that his chat with me wasn’t changing much, that Niue was not going to survive.

“We have to accept that there is no money laundering going on in Niue, or even through Niue,” Mossack said, becoming angry. “Any IBC [international business company] registered in Niue is used in the Far East, in Hong Kong or Singapore, to open bank accounts.

“Are they a threat to New Zealand or the New Zealand dollar? I cannot see it, I don’t see a connection.”

He believed people like me were picking on his company because they were from Panama.

“Why is somebody who is based in Panama any different, any worse, than somebody based in the United States or Europe? Panama is a country like any other, it is an on-shore country, it is not an island in the middle of nowhere.”

*

Now his firm Mossack Fonseca is back in the headlines, and other journalists are chasing some of the stories that once were pretty much mine alone.

It’s an odd feeling. You get to a certain age and you realise the same stories just keep on coming back. I cannot easily explain it; not history repeating and all that. Something else.

To write this piece I delved into my files and was, for a moment, perplexed to find that my last piece on Jürgen Mossack was published in Rupert Murdoch’s smallest and now long-gone publication, the Suva-based Pacific Islands Monthly.

An odd place, I thought, to leave such a story, but then I spotted the date: it was the April 2000 issue.

A month later a man walked into the Fiji Parliament during a session and proclaimed: “This is a civil coup. Hold tight, nobody move.”

One headliner, Mossack, was giving way to another who was to become a constant presence in my life for the next five years. His name was George Speight.