The former prime minister’s campaign against unbridled power continues.

The Nation Is at Risk, the second episode of Juggernaut: The Story of the Fourth Labour Government, is now available wherever you get your podcasts.

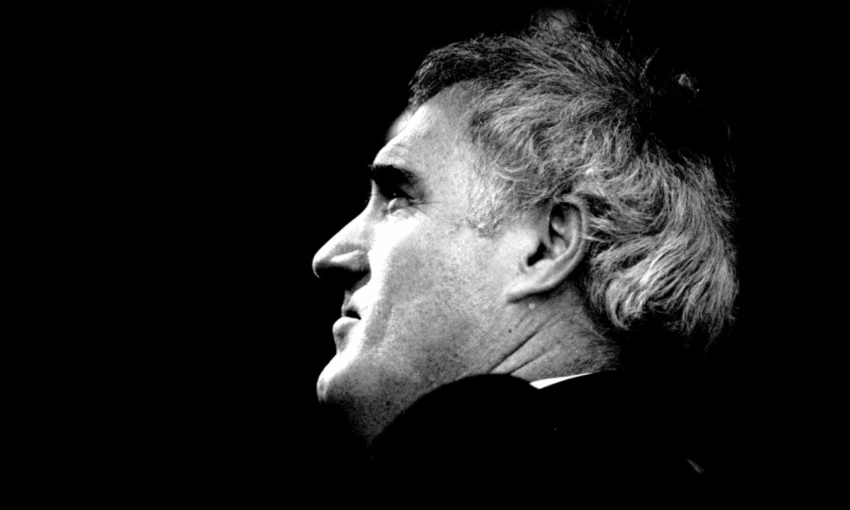

Geoffrey Palmer has been raging at the executive for ages. In the late 70s, while on academic leave at Oxford, he wrote Unbridled Power? An Interpretation of New Zealand’s Constitution and Government. Inspired and appalled by the leadership style of then New Zealand prime minister (and finance minister) Robert Muldoon, he inveighed against a system of government that vested so much power in the executive branch, with the cabinet table its mighty nucleus. With so few checks or balances built into the system, executive power was largely unbridled, making New Zealand “the fastest law-maker in the west”.

Forty-five years after the publication of that seminal book, and 40 years after its author formed part of a government which enacted remarkable, radical and rapid reforms of its own, Palmer is aghast at another example of what he considers executive overkill. The Fast-track Approvals Bill reminds him of the Muldoon government’s National Development Act, which allowed that administration to bypass a bunch of existing laws for projects of national importance under the Think Big banner.

That bill – thrown out by the government in which Palmer was deputy prime minister in 1986 – should serve as a warning to Chris Bishop, Shane Jones and Simeon Brown, the three ministers who, in its current form, would have the final say over green lighting projects and exempting them from a range of processes including environmental scrutiny, he said.

“I do think that ministers have to be given the credit for the fact they’re trying to do the best they can,” said Palmer. “I don’t know many ministers who went into parliament with any other aim than that. But I have to say, if you look at the history, the National Development Act did not work. It had to be abandoned. It was repealed. I think when you have historical examples like that, you should learn from it, not repeat it.”

The fast-track bill, which received more than 25,000 written submissions and prompted a large demonstration in Auckland earlier this month, is currently at select committee stage. Bishop has indicated that he is open to making changes to the legislation before it returns to the House.

Speaking to the Spinoff in his office at Old Government Buildings in March for the podcast series Juggernaut: The Story of the Fourth Labour government, Palmer raised the alarm also about the “vast amounts of urgency we’ve recently had”.

The current coalition government has set records in its use of urgency provisions to push legislation through the house. Fourteen bills were passed under urgency, without recourse to a select committee, inside seven weeks earlier this year. “You can’t do that in most countries, because there are two houses. I do not advocate another house. But we need to slow the system down and look at what we’re doing,” said Palmer, who has long sought to put New Zealand on a path to a written constitution.

Palmer invoked the phrase coined in 1991 by Leslie Zines, the late Australian constitutional scholar, of New Zealand as an “executive paradise”. “It was and it is,” said Palmer. “And the way in which our government functions needs to be changed so that it is more democratic. We’ve gone from being the fastest lawmakers in the west to the fastest repealers in the west. And I don’t think that’s a good thing. You can’t have enormous programmes binned when a new government comes in, because the cost of doing the replacements are enormous, and the time to do them is enormous, and the transaction costs to the economy are very high.”

He continued: “We do not make law in a good way in New Zealand, and we need to improve it. We’ve been doing this since about the 1860s. And we’ve hardly ever changed it. All the law is prepared in the executive branch in secret. The public servants can’t speak about it. The result is thrust on an unsuspecting public and a parliament. And then it’s passed after what is often perfunctory scrutiny by a select committee. That means that we have a lot of policy failures. We have blunders in policy. They have to be repaired as a result of this behaviour. And until we understand what it is we’re doing wrong, we’re just going to repeat the mistakes.”

The government of which he was a key member was renowned, among other things, for the volume and pace of reform it enacted. Was he comfortable with the speed of change then?

“No, I wasn’t,” he said. “The policy process that Roger Douglas favoured – ‘crashing through’ – really is not the way to make enduring policy. And in a democracy, you can’t afford to have policy that doesn’t endure. The life of policies is getting shorter and shorter, the statutes get replaced quicker and quicker. And you can’t go on like this.”

The uptick in urgency goes hand in hand with the embrace, under governments of both stripe, of the 100-day-plan approach to ticking off legislation. “I think the 100 day thing has gotten out of hand,” said Palmer. “And you only do this, because you can, because in New Zealand, there’s nothing to stop you. It’s not sensible. It’s not rational. You do it without advice. And the advice is critical to avoiding error.”

Palmer was an architect of the Resource Management Act, which ended up being passed by the National government in 1991. “I’m very fond of the RMA,” he said. “It didn’t work, because local government wasn’t up to the task. And central government didn’t pay any attention to it. The bill became more than twice the length it originally was. It lacked coherence. [In 2023, David] Parker had to do what he did to revise it. That was all repealed under urgency. Now they’re going to do it all again. The replacement is years away. You cannot in a democracy have law made that way, where you have chronic uncertainty for so long about what is actually going to happen. It’s not sustainable.”

Palmer was instrumental in a profusion of other major legislative reforms. The Public Finance Act, the creation of a Ministry for the Environment and Department of Conservation. The Bill of Rights. The extension of scope of the Waitangi Tribunal back to 1840.

He also managed to get a Royal Commission on Electoral Reform set up. Few held out much hope for that to translate into action: the first-past-the-post status quo suited the big parties. Why would they change? And then the prime minister gave a speech and pledged a referendum. “He got up and pulled out his notes and misread them. There’s no doubt about that. And the result was that the National Party also offered a referendum on it. And that is what led to it being accepted,” he said.

“There are contrapuntal harmonies in New Zealand politics, and that’s a good example of one.”

Palmer played an integral role in the fourth Labour government as deputy prime minister, attorney general and justice minister. Following David Lange’s resignation at the end of a brutal conflict with Roger Douglas, Palmer became Labour leader and prime minister in August 1989. A year later, with an election six weeks away, he was rolled by his caucus for Mike Moore.

“I never wanted to be leader of the Labour Party because I had an almost perfect set of portfolios for my interests,” said Palmer. “There’s a lot of rubbish connected with being the leader, you’ve got to be a sort of entertainer and all sorts of stuff that didn’t interest me. But I felt I had to do it to finish the programme. Because we had a big programme legislatively and we needed to finish it.”

When Moore challenged, “I thought, well, good luck to you. And I was able to go and do some more interesting things.”

Asked to assess his own achievements in politics, Palmer put it like this: “The difficulty you have with ministers is that they have illusions of power. They believe that they can do anything. But it turns out doing it is much harder than saying they’re going to do it. And it often doesn’t work. One has to be very humble about these things.”