Should a convicted murderer be allowed to help run a charity? Can you start a charity to support your addiction? Should Greenpeace and Family First be treated differently? These and other issues are being addressed in the Charities Act review.

How do you know that when you donate to a charity, your contribution is going towards something worthwhile? How do you know that some random hasn’t created a fake charity in order to support their addiction to tropical fish? The short answer is the Charities Act (2005).

This Act created a regulator for charities in New Zealand and a central register. You cannot be a registered charity and gain the all-important CC number without being registered with Charities Services. In order to be registered, you need to fulfil certain requirements, like listing your officers and their details, submitting annual returns, paying an annual fee, and establishing a charitable purpose that the regulator agrees to. All of this is available to the public through the online Charities Register. This set up is designed to foster trust between charities and the public, so that you know Geoff and his exotic fish aren’t the real beneficiaries of the cash you put in the local collection box.

Aotearoa in 2019 isn’t quite the same universe as Aotearoa 2005 when the Act came into force. Donations via social media platforms have developed dramatically, while traditional fundraising methods such as mail campaigns are becoming a relic of the past. A new generation of donors is emerging, one which has different priorities for how they engage with charities. Brian Tamaki was ordained as a bishop. Things have changed, and the Charities Act needs to keep pace.

That’s why the Department of Internal Affairs (DIA) is taking public submissions – the last day is today! – on how we should modernise the Act. Like a first year uni student getting used to deadlines, we’ve been granted an extension by Hon Peeni Henare to contribute to this review. You are pretty much certain to have engaged with a charity as both a donor and a beneficiary at some point. There are over 27,000 of them in New Zealand, and they include things like sports clubs, churches, school Trusts, universities, orchestras, and art galleries, as well as the big hitters like Starship or World Vision. So, what kind of things can you weigh in on when it comes to how Charities operate in Aotearoa?

Baking cakes

Last week, Vu Le, a charity director from the United States, was quoted in RNZ making the following delicious analogy:

“…if we had a bakery and we go in, you ask to buy and cake and you say you know what, I want all of this money to pay for the ingredients, I don’t want any of this money to pay for the baker’s salary, or the electricity for the oven…how is this cake going to get baked? And if it is baked, is it going to be a very good cake?”

He is referring to the familiar “overheads conundrum”. Charities are often pilloried for spending too much money on administrative costs such as having an office or paying people to run things and fundraise instead of carrying out the charitable purpose of the organisation. As this analogy suggests however, it isn’t really possible to separate the charitable purpose of an entity from the need to simply stay open. Isn’t that part of why we give money to a charity in the first place, to outsource our good deed doing?

The review asks us to consider the question of whether or not staying open is, in and of itself, a charitable purpose. Some smaller charities can rely solely on volunteers but for many this simply isn’t possible, or even wise. The recent controversy surrounding Victim Support and its handling of the extraordinary amount of money donated to the victims of the mosque shootings on 15 March has highlighted this issue for those who work in the sector and for donors. It’s a highly unusual situation, but one that presents an important precedent. This charity found themselves kaitiaki of their entire annual turnover virtually overnight. Unsurprisingly, they were administratively overwhelmed. In response to criticism, they vowed that “no portion of the money you donated will be used to cover administration expenses”. Jemma Balmer discussed this issue in more depth in her Spinoff article.

The accumulation of funds, the operating of “unrelated businesses” like op shops or cafes, and the question of when and why charities should be struck off the register are the main areas where we are being asked to think about this issue. The review team want to know if charities should be allowed to build funds up and reinvest them when they have a surplus, or whether we should require them to spend a certain portion of those funds each year as they do in Canada (the review discussion document really likes comparing things to Canada). They also want to know what the registration requirements for things like op shops should be.

Charities tend to live longer than businesses – almost 80% of the top 40 charities in New Zealand are over 20 years old, in sharp contrast to the for-profit sector. Part of this is down to a more conservative attitude to risk-taking when it comes to financial management, and the considered re-investing of unexpected bequests and other circumstances that might lead to surpluses (they don’t tend to give their CEOs enormous bonuses at the end of the financial year either). It also means these funds have the chance to accumulate pretty significantly, which is why these questions are so important to the review.

Charities noir

Here’s one of the juicier questions posed by the Charities Act review – should a convicted murderer be allowed to help run a charity? Currently, the answer is yes. In order for a charity to be registered, none of their officers (that’s no one who has control or influence over the organisation, such as a staff member, Board member, or significant volunteer) can have been convicted and sentenced for a crime involving dishonesty (fraud, theft, forgery, tax evasion etc) within the last seven years. If someone has committed murder, rape, serious assault, or any other crime, then theoretically the Charities Act allows them to be the chair of the Charitable Trust for the Protection of Adorable Puppies.

This might seem counter-intuitive, but there are plenty of charities for whom having an Officer who has been convicted of a serious crime can be very beneficial. Preventing the Ex-Prisoner Residential Trust or Prisoners’ Aid and Rehabilitation Society from involving former prisoners in their governance seems unreasonable. Also worthy of consideration is the opportunity for people who have been convicted of serious crimes to rebuild their lives and give back to communities. Finding employment can be extremely challenging, and volunteering is often an essential pathway towards rebuilding a life on the outside.

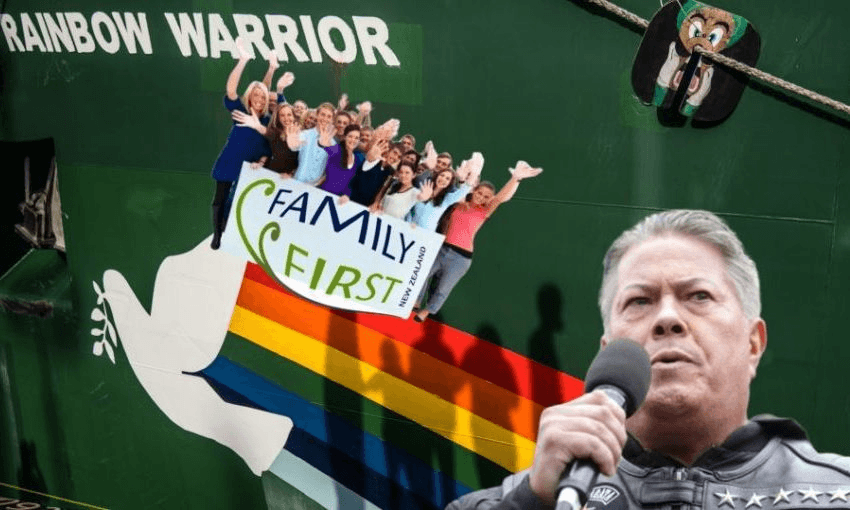

Destiny Church, Family First, and Greenpeace

They are an unlikely trio, but these three organisations are the reason behind the final and probably most significant section of the Charities Act (2005) review submission document. Back in 2013, Greenpeace won a victory in the Supreme Court following cases in the High Court and Court of Appeal regarding their charitable status. They contended that their political advocacy was a charitable purpose, and that they should be allowed to register. The Supreme Court agreed that “charitable and political purposes are not mutually exclusive”, to quote Chief Justice Sian Elias, and I imagine Lucy Lawless treated herself to a nice glass of organic merlot that evening. However, in 2018, the Charities Registration Board declined Greenpeace’s application to be a charity. They decided that Greenpeace “does not advance exclusively charitable purposes”, and also considered the illegality of some of their actions. No merlot for Lucy.

In tandem with this decision, Family First was having its own divorce proceedings. The Charities Registration Board deregistered Family First in 2013. Unsurprisingly, Family First didn’t find this particularly family friendly, and appealed the decision. It was agreed the parties would hold off proceedings until the Greenpeace Supreme Court decision had been made so that the Charities Board could have a precedent to go on. After a couple more years of back and forth, the Courts concluded that “promoting the traditional family unit (as defined by Family First) was not beneficial to the community in a way recognised by law.”

These decisions are pretty fascinating, not least because if you support Greenpeace and want them to have charitable status, you’re unlikely to feel the same way about Family First and vice versa. In this regard, they provide highly useful precedent because they force many of us to divorce (pun intended, sorry Family First), our opinions on the content of the advocacy from the concept.

The latest charity facing contention in this regard is Destiny Church (although their inability to file a return is more likely to see them deregistered in 2019 than any high-concept legal arguments). Once again, the review has proved timely in its consideration of what kind of advocacy charities should be able to engage in. Is it possible to separate the charitable purpose of an organisation like Amnesty International from its advocacy? If a business can endorse a political party, why can’t a charity? Many charities exist because of some shortfall in the current law or public system, so isn’t advocating against this shortfall intrinsic to their existence and therefore their charitable purpose? It’s important to interrogate how we feel about these issues in relation to political causes we have differing views on. If you think Destiny Church should be deregistered, ask yourself if you feel like the same rules that deregister them should be applied to a cause you support and donate to.

Charities as kaitiaki

Central to all of these considerations is the idea that charities are the kaitiaki and not the owner of donor’s funds. They face a pressure and responsibility that the private sector does not when it comes to how they utilise those funds. This ethos is entrenched throughout the sector and the laws governing it. For example, a museum is not the owner of the objects it cares for and displays, but the kaitiaki, as governed by legislation like the Protected Objects Act 1975. Sometimes this concept has less desirable results, like keeping salaries far below those of other sectors. Given that 80% of those who work in the charities sector in New Zealand are female, this is something worth questioning. However, in order for the public to feel confident donating to charities, they need to be able to trust that these organisations will be honest and responsible kaitiaki of that donation. We need to know that Geoff won’t splash out on his tropical fish.

You can answer any or all of the questions posed by the Discussion Document, and I’ve only scratched the surface here. There are sections on Te Ao Māori, third party fundraisers (think people in malls soliciting donations), and the attorney general. If you’re not keen to do a submission (and fair enough too), take some time to check out the Register. Search for charities you’ve donated to recently, or come into contact with, or benefited from, or heard about and wondered about. They all have to provide their annual returns, their officers, their rules and their purpose.

New Zealand’s charities sector contributes 2.8% of our GDP, employs over 100,000 people. If you include volunteers, over 10% of us work for a charity. We need to be able to trust them, and they need to be able to do their work without unnecessary restrictions. Finding that balance is difficult and needs to cover the requirements of over 27,000 organisations as diverse as the Royal New Zealand Foundation of the Blind, Māori Television, and the Eketahuna Volunteer Fire Brigade. Charities are the kaitiaki of our funds and wellbeing, but we are also responsible for their health and for their ability to carry out their charitable purposes. Submissions close today.