Back in 2017, The Clean won the Taite Music Prize’s Independent Music Classic NZ Record award for their 1981 EP Boodle Boodle Boodle. Hussein Moses talked to the band and those involved to dig up the inside story of a record that became a New Zealand legend.

First published in April 2017.

It was a defining moment in New Zealand music history. In September 1981, The Clean – brothers David and Hamish Kilgour, and Robert Scott – entered a makeshift studio in Auckland’s Arch Hill and emerged with Boodle Boodle Boodle, one of the country’s landmark records that would soon put Dunedin music on the map.

The five-song EP, recorded by Chris Knox and Doug Hood and released on Flying Nun Records, followed the jangly single ‘Tally Ho!’, which had come out that same year and found its way to number 19 in the New Zealand charts. But Boodle would push things even further, eventually peaking within the top five and spending a good six months hanging around on the chart. Not bad for a handful of songs that commercial radio refused to play. Thirty-five years on from its release, the record is still as relevant as ever.

Roger Shepherd (founder of Flying Nun Records): The first time I saw The Clean was in 1978 at their first gig in Dunedin supporting The Enemy. I travelled down to see The Enemy, and The Clean just happened to be playing in their first line-up. They were very rough, but kind of interesting in a post-rock way. Then I saw them again in 1981 at the Gladstone in Christchurch. They were clearly the best band in the world without question.

David Kilgour (band member): We were in Auckland and our mother got hold of us and said this guy Roger Shepherd’s trying to get hold of you guys about a recording. So the first time we met Roger was in Auckland. We were there for about a month doing some shows and living in Ponsonby. Roger tracked us down to our house there and that’s how we first met him.

Roger Shepherd: They had gone through a whole lot of different bass players which hadn’t worked out and then they finally found Robert Scott. He was the glue that kept it all together.

Robert Scott (band member): I hadn’t really properly played in any other bands as such. I had sort of mucked around with some guys that I grew up with around out in Mosgiel. But that wasn’t a proper band, it was more cardboard boxes and pianos and acoustic guitars. I was flatting with David’s partner, so he’d be at the flat quite a lot and we started jamming together in 1980. Musically, we got on really well.

David Kilgour: We were writing all the time. We would get together and we’d just try and write and also try and get better as well. We’d get together three times a week here in Dunedin and rehearse and practice, which looking back now seems quite obsessive. Hamish [Kilgour] and I were pretty hell bent on doing something, so once we met Robert things moved along a lot quicker. We did work pretty hard and we were obsessed with writing all the time. We were never happy with what we had just done, we always had to write more.

Roger Shepherd: They were clearly way ahead of the pack of anything else I’d seen at that stage. Three different songwriters, David’s guitar playing was astoundingly different and unique and original, the songs were great. There was Hamish doing his agitprop thing and Robert’s songs were different again.

David Kilgour: I guess Hamish and I had always felt alienated from society, especially as young teenagers. There was rebelliousness there, but what Hamish used to say back in the day was that the songs are really about paranoia.

Doug Hood (producer/engineer): It was quite a depressing time back then. It was around the time of the Springbok tour and all that. New Zealand wasn’t much of a fun place. But The Clean were pretty much non-political and a breath of fresh air.

David Kilgour: I’d known Chris Knox and Doug Hood since I was about 15 and Hamish was good friends with them as well. Up to that point, we’d be recording ourselves on a Revox 2-Track and overdubbing and doing stuff like that. Then we heard what Doug and Chris had been doing, especially one track by the Techtones, which Doug had recorded with them. We were quite impressed with that. What really blew my mind was the Tall Dwarfs’ first EP [Three Songs]. Chris and Alec Bathgate had just recorded that and I can always remember listening to that straight off the 4-track before they had mixed it. It just seemed like a logical extension to record with them, really.

Doug Hood: I was Toy Love’s soundman, so I’d had a bit of experience in live mixing. When Chris bought a 4-track, we were living together in Grey Lynn and he started playing around with it. I basically borrowed it off him and I recorded a band called the Techtones and discovered that you could actually mix 16 tracks down to four tracks, which is what we basically did.

Roger Shepherd: They just thought they could record The Clean better on Chris’s 4-track than we could otherwise. The feeling was that there’s five or six songs ready to record; let’s just go with that and make an EP. It takes out the stress of trying to put an album together. That was the great thing about the EP format: a lot of the bands that came after them had an EP’s worth of songs but not an album’s worth, and it reduced the whole stress of recording.

David Kilgour: We were sceptical of going into fancy studios. They seemed a bit alien to us really.

Roger Shepherd: They recorded it in Bond St in that hall that I hope is still there. It cost $750. I paid for it.

Robert Scott: It wasn’t a studio. It was like a Scout den hall. It was very small. It would’ve been ten-by-ten metres, or something like that. There’s was a wee room off to the side that would’ve been the kitchen. Doug and Chris set up the 4-track and soundboard in there and just ran the mic lines out into the main room. We just set up in the main room as though we were playing live.

Roger Shepherd: The misconception is that it was all Chris, but it was very much Doug. It was Chris’ machine, the 4-track. Doug was very much engineering the whole technical side of it and the ins and outs of recording it. Chris was essentially there as another set of ears. He was like another producer, whereas Doug was kind of engineer/producer.

David Kilgour: I worked out that I turned 20 the day before we started recording it. It was an exciting time, of course. We didn’t really know what we were going to produce when we went to make that record. We were never that interested in capturing the band and what it was like live; we were much more interested in producing an interesting record. I wouldn’t say that record has any relation to what we sounded like live at the time, apart from the energy.

Doug Hood: I knew ‘Point That Thing’ was really special and ‘Anything Could Happen’. I don’t know exactly how we got the sound we got on ‘Anything Could Happen’, but for such a basic recording it’s still to this day sounds really fucking good. We had no playback facilities at all. We couldn’t really even listen to anything until we got it home and listened to it on the home stereo.

Robert Scott: ‘Point That Thing Somewhere Else’ stood out for me because it’s such an incredible piece of music, and it’s one of those songs that’s different every time it’s played as well. So capturing a good version of that was great.

David Kilgour: I don’t know what it is about that song. It was a bit of a pivotal moment coming up with that track. Up until that point, we had been playing it as quite a metallic fast track. I think by the time we came to record it, we were a bit tired of that and we just went the opposite way. I think once we had done the guitar overdub, we knew we were onto something pretty special. Actually, when I was doing that guitar overdub, Chris Knox walked into the room where I was recording and sat down and had a fit. I’d never actually been with Chris before when he’d had a fit, so it was a new experience for me. I wasn’t too sure what was going on.

Robert Scott: I was kind of freaked out because I’d never seen anyone have an epileptic fit before and I didn’t know Chris was an epileptic. The others said ‘it’s alright, he’s just having an epileptic fit. He’ll be alright in a few minutes’, and he was. Apparently it can be brought on by excitement and I know Chris was really excited about the way the sessions were going and he felt that something pretty good was getting put down that day. It all added to the craziness of the day.

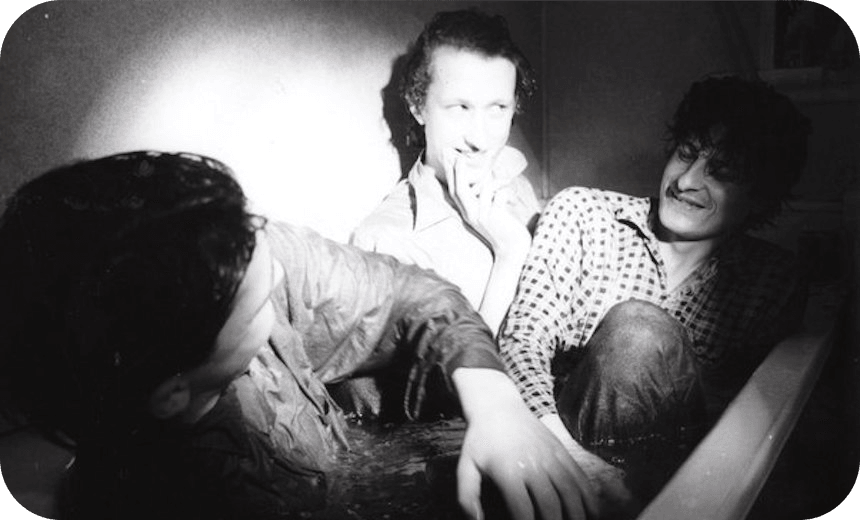

Robert Scott: We were doing a photo session at Chris Knox’s flat and Carol Tippett was taking photos for press stuff. We were also shooting a video in the bath at the same time and eating grass. So that’s what’s happening in the bath. I’m pretty sure that Chris just did the drawing from a print from that session. That was put forward as a cover idea and we went ‘yeah yeah, sure’. The back is all of our rough ideas of what we could’ve done for the cover.

Roger Shepherd: It was always a great dilemma in Flying Nun circles, what we were going to call a record. That’s why the label’s got a stupid name. I think Barbara Ward, Chris Knox’s partner, came up with Boodle Boodle Boodle as they were just sitting around going ‘what are we going to call it?’ They latched onto it because it just sounded great rather than what it meant. And probably what it means is something to do with money, I suspect. It’s probably some English upper-class phrase like tally-ho, now that I think about it.

Robert Scott: It’s slang for money and it’s also a kind of English gin.

David Kilgour: It was a term that Barbara’s family I think had used as kids. They might’ve used it to fill in swear words perhaps. I can’t actually remember.

Doug Hood: We were all saying it was going to be a real hit and we’d make lots of money and she said ‘yeah, lots of boodle’. And that’s how it got its name.

Roger Shepherd: I couldn’t believe how good it was. I think we might’ve gone for a blat in my Jaguar Mark 2 because it had a decent stereo. I was just blown away by it. It sounded so much better than I thought possible. It finished on ‘Point That Thing Somewhere Else’, which sounds great in the car. It’s a good driving song, that one. It’s a really varied record. I’m just so fond of it. It’s such an important record for Flying Nun and for New Zealand music. It showed the way forward for all the other bands that we worked with afterwards.

David Kilgour: I heard those tracks straight off tape recently for the first time in quite a long time and I was really surprised at how good they sounded. Especially the drums and bass, which were coming off one track. ‘Point That Thing’ and ‘Billy Two’ and ‘Anything Could Happen’ – God, they sound so good and it’s coming off one track. It was kind of astonishing to hear.

Martin Phillipps (The Chills): They caught something special. At the time it was easy to miss the sheer intensity of what The Clean were like. But they did the more sensible thing and recorded those songs played really well in the studio. And that’s what’s going to last – not people’s memories of this gig or that gig, that’s redundant. If you can catch a song that’s going to last longer than you are, that’s special.

Roger Shepherd: It showed all those bands what could be done on a 4-track and it eased a lot of bands that would’ve been freaked out in a studio environment by the expense and the snooty attitude of the people that worked in them. A lot of those bands would’ve reacted really badly to that. It also showed them what the sales potential was. Over time, we’ve probably sold about 20,000 copies of that record. I thought it was good enough to do really well, but it was top five in the charts twice. It was up there before Christmas and then bounced back up after Christmas, so it gives you an idea of just how much interest there was in it and how much people liked it. It sold on a grassroots level of people seeing the band, or people talking about it in record shops or people reading music writers in newspapers and Rip It Up. Commercial radio never played it, so it was a bit of an ‘up yours’ gesture, the whole thing.

Martin Phillipps: It was a pleasant surprise but not totally out of the blue. The Clean toured extensively throughout New Zealand and a lot of audiences who thought they didn’t like that kind of music found that they did and went out and bought the record. It was the grassroots support for the band that paid off for that record.

Doug Hood: I read a comment from Martin Phillipps, where Martin said he finds it really difficult to listen to stuff from back then. But I don’t think you can say that about The Clean. It’s as relevant today as it was thirty-odd years ago.

Robert Scott: I suppose it’s one of those things – fate and all that kind of palaver – just bumping into the right people at the right time and everything conspiring to work out as well as it did. I just consider myself very lucky.