An autobiographical theatre show tells Jodee Mundy’s experience being a CODA – a child of deaf adults – and reveals many shortcomings of a world designed for the hearing.

When Jodee Mundy was five, she got so caught up staring at a Barbie in its box with a tennis racquet and a little ball, that she lost her mum in Kmart. After searching high and low, she went to the front desk, where the shop attendant asked her name and then blared it over the loudspeaker: “We have a lost child – can the mother of Jodee please come to the front desk.” But Mundy’s mum didn’t come, even after several announcements.

A slightly panicked Mundy eventually found her mum in the racks of the clothing section and they were reunited. The tiny Mundy wanted to know why her mum hadn’t come to the front desk after the announcements. “I’m deaf. You know that!” signed her mother. A pin dropped for Mundy. Of course she knew her mother was deaf, she just hadn’t realised it meant she couldn’t hear.

This the beginning of an autobiography that Mundy shares in Personal, a theatre show about her experience being born hearing into a deaf family. Throughout the show she expresses frustrations at how society is designed in ways that do not take deafness into account. As a result, she was often the intermediary between the hearing world and her family – taking phone calls, ordering food, translating her own parent-teacher interviews – and she noticed that the world treated her differently to her deaf family members. Later she learns there’s a name for kids like her – CODAs [Child Of Deaf Adults] – and a big international community.

Mundy is a well-established creative in Australia, but as she told the audience who stayed for the Q&A last Friday at Q Theatre in Auckland, for a long time she was hesitant to make autobiographical work. She closely guarded her personal story until her early 30s, when she started to write a children’s book about it. In the process of writing, she realised that “this wasn’t just my story, it’s a collective story, it’s a universal story. It’s a deaf community story, but it’s also the wider world”.

Still, she was reluctant to take the story to the stage, despite that being her primary medium. It wasn’t until her mum and her brother gave her a whole raft of family videos and she looked through all the moments captured – deaf camps, deaf Church outings, vacations, a school interview with her teacher – that she realised it should be a performance. These videos play a vital role in the stage production.

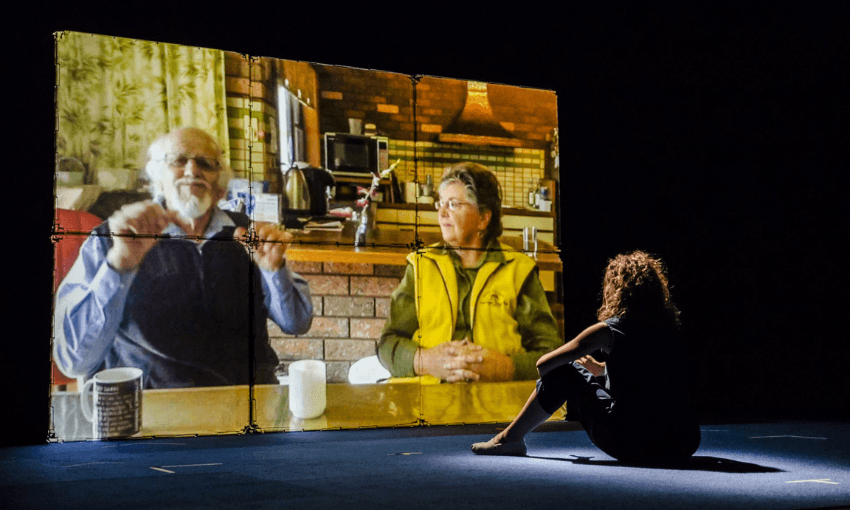

The show is part one-woman performance and part video installation. On stage with Mundy are six identical grey cubes, each about a meter wide and tall, and different coloured markings on the floor. Throughout the performance, the cubes act as a series of projection screens, in a carefully choreographed progression they are moved around by Mundy, creating a series of different sized videos. As stagecraft, it worked wonderfully. Simple enough to be elegant, but surprising enough to be interesting and add presence to the projections. Add to that the fact that Mundy’s performance was often in tandem with or interacting with the videos and the choreography becomes even more impressive.

The videos come from a variety of sources, including the family’s archive. There’s also vintage educational footage that Mundy starred in as a child which is reworked as part of the narrative, and animation and interviews with her parents and brothers that have been produced specifically for the show. Mundy speaks in English and Australian Sign Language, alongside captioning in the videos. The result is a story that is told equally to the deaf and hearing audience (indeed on Friday much of the audience showed their appreciation with silently tinkling hands).

One telling moment captured from Mundy’s childhood comes when her well-meaning primary school teacher is interviewing her in front of the class about what it’s like to be in a deaf family. “How do your deaf brothers get to school?” she asks a smiling, squirming Mundy. “They walk.” There are other moments of entertaining dissonance too – when telecaptioning started appearing on TV, the soap Neighbours had it before the news. Mundy recalls translating a bulletin about a wall coming down somewhere called, “B — E – R – L – I – N”. She could not understand why there was so much excitement about it.

CODAs have a foot in both the deaf and hearing worlds – Personal shows the pressure and overwhelm that Mundy felt as a result. The soundscape of the show at times acts like an intrusive presence that she is battling. But now, Mundy is an adult. She has chosen to become an interpreter, and describes herself as a hearing person with a deaf heart. Mundy’s character arc is proven by the existence of the show, which in itself is a bridge between the deaf and hearing worlds. It is a generous and beautifully conceived piece of art and advocacy.