Pip Adam reviews the Netflix adaptation Patricia Highsmith’s famous novel, which is dividing critics.

Recently, 1,000 victims of human trafficking were freed from scam factories in Myanmar. While tech billionaires live off the profits from selling the information their platforms produce, these factory workers use this same information to engage in online ‘pig-butchering scams’. This is the face of the con in our immediate moment of Late Capitalism.

Crime is a complicated genre, but more than any other it speaks back to the conditions it is created in. Steven Zaillian’s re-telling of Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr Ripley is in conversation with capitalism’s celebration of some work and neglect or condemnation of others. This re-introduction of Tom Ripley as the skilful worker is what makes Zallian’s Ripley both the most controversial and, in my opinion, probably the best.

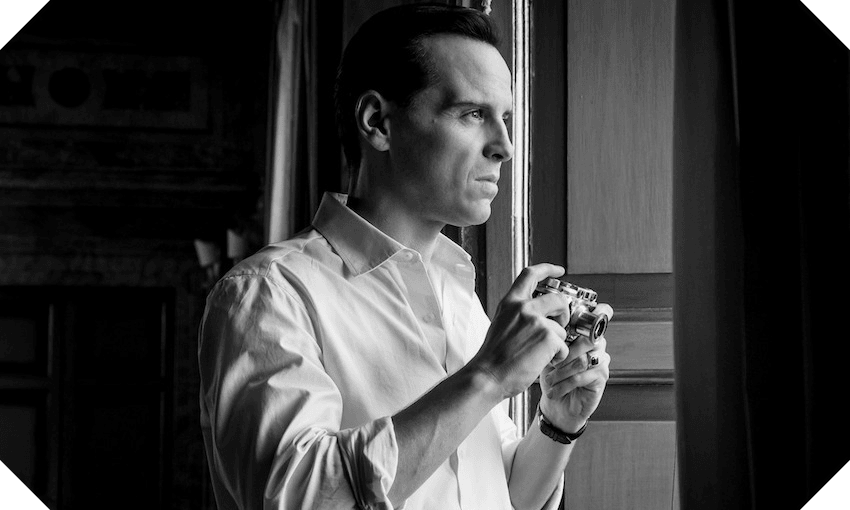

Infamously, Tom Ripley, having few options open to him, goes to Italy to bring home the wealthy heir Dickie Greenleaf but instead brutally murders him. Andrew Scott’s Tom Ripley tells a private investigator what he knows about Dickie:

“He comes from a wealthy family as you know. He came to Europe years ago to get away from it. He said he wanted to be a writer but never wrote anything. He said he wanted to be a painter but knew he could never be that either. He wondered if he would ever be good at anything. Everything about him was an act. He knew he was supremely untalented.” – Ripley, Episode 8 – VIII Narcissus

On the surface, this monologue appears to be Ripley inadvertently telling on himself while condemning Dickie. Isn’t the con-artist Tom the one who is acting? Ripley becomes Dickie for a period and as the “bad” man masquerades as the “good” both men’s moral lives entangle. As Tom forges his signature for Dickie’s allowance we are reminded where the money comes from, of the workers we’ve seen labouring in Dickie’s father’s factory.

The violence done by Tom echoes the violence of the factory floor – the heavy, partially-constructed wooden boat precarious over workers’ heads as they weld; sparks flying. So, when, in the final scenes Tom tells his story we can’t help but believe his assumption that Dickie, product of the American Dream, is the failed writer, the terrible painter who lived off the hard labour of others and produced nothing of worth.

Many critics, when analysing Tom’s crimes, focus on what Ripley wants more: Dickie (pun intended) or Dickie’s privileged life. I’ve always felt this binary oversimplifies Tom’s motivations which I think are much closer to and as profound as the motivations of most workers – to make a living, do a good job and not lose livelihood. Unlike other adaptations, Ripley’s queerness is not the central “problem” of this re-telling. This is not the story of a lone queer character thrown into a straight world unable to control his urges resulting in violence. Instead, queerness is integrated in every aspect of the story.

In Ripley, Eliot Sumner’s perfect portrayal of Freddie Miles reminds us, without fanfare, that it is simply a fact that trans and non-binary people have always been and will always be. Zallian’s is a world, like Highsmith’s novels, where Ripley is not having trouble getting sex and that any burden his queerness poses is far more from the society he lives in than any struggle he has with himself. This Ripley kills Dickie not because he can’t have him, but because Dickie’s change in attitude presents a barrier to the continuation of Tom’s livelihood.

Highsmith is the master of guilt and it is guilt, not loss, that forms the base struggle of Zallian’s Ripley. An amplification of the guilt any worker feels as part and parcel of their work in our high Capitalist era. I think the idea of Ripley’s crush on Dickie is an easier swallow for most audiences. Love seems a higher motivation for murder than financial survival and I think this is part of what is making this adaptation unpopular with many critics.

Another factor in the trouble some viewers are having with this adaptation is how extremely unlikeable Andrew Scott’s Tom Ripley is. This Ripley is not charming, he doesn’t have the gift of the gab or the charm of the ingénue, instead his criminal competence seems to come from his ability to endure the awkward silence and an immunity to what other people, especially the rich, might think of him. Marge says of Ripley, “he’s a liar, it’s his profession” – and he’s an extremely hard worker. Lying is presented as a twenty-four-seven profession and Ripley as a sole-trader.

The long scenes detailing the murders and resulting cover-ups Tom perpetrates do a good job of showing the hard physical labour involved in murder. These extended real-time scenes expose another KPI of the job, as every action opens another possibility for exposure. A bloody scarf left in the bathtub, a missed stain on the marble stairs. Ripley becomes a better painter than Dickie and possibly a better Dickie than Dickie, but he never makes a complete class-shift – Marge and Freddie simply don’t like him. Unlikeability is a trait society almost demands in our current tech leaders but it doesn’t like much in us workers.

While earlier adaptations offer escapism through the promise of a life of wealth and leisure, Zallian’s Ripley offers an opportunity for us to reflect on how we are being conditioned to value work and judge talent.