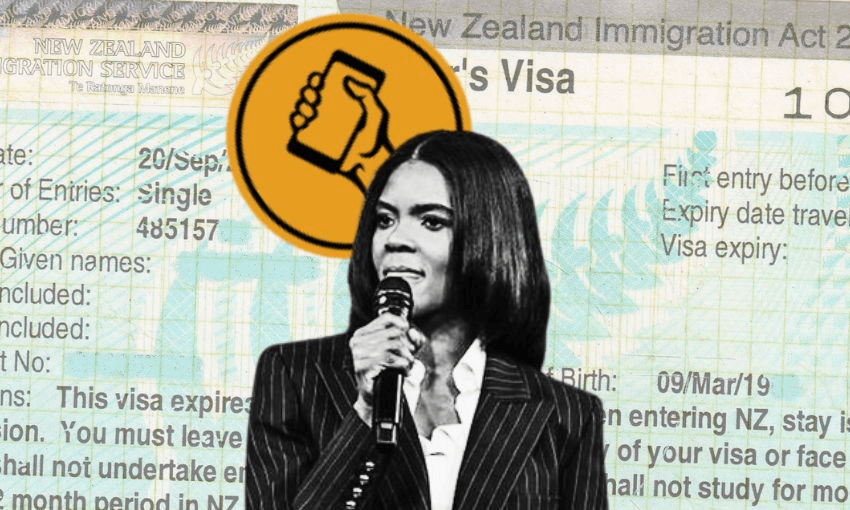

Late last year, the associate immigration minister reversed a decision to deny the controversial US commentator a visa, after a local lobby group put the pressure on. Documents released under the Official Information Act reveal how it unfolded.

Across the ditch, her risk of “inciting discord” was deemed too great to allow her into Australia. But in Aotearoa, ministerial discretion was used to overturn the rejection of Candace Owens’ visa application, with the right to practise free speech – hers considered by many to be antisemitic, transphobic, racist and extremist – considered to outweigh considerations of her being an excluded person.

So how did it happen? Documents released under the Official Information Act reveal the process that led to associate immigration minister Chris Penk overturning Immigration NZ’s decision to deny Owens a visa to visit New Zealand for a speaking event, after the Free Speech Union went in to bat for the controversial conservative American commentator.

Owens – named as the person who influenced the Christchurch shooter “above all” in his own manifesto – will deliver a speech at Auckland’s Trusts Arena next January (if you haven’t already grabbed a ticket, sales have been paused). She was due to host her first-ever live event on New Zealand’s shores in late 2024, but a decision on her Australian visa by that country’s immigration minister Tony Burke had a ripple effect across the Tasman.

Due to her “controversial and conspiratorial views”, Owens was refused entry into Australia in October – and under the Immigration Act 2009, this provides grounds for INZ to exclude Owens from Aotearoa, too. However, hundreds of documents released under the Official Information Act reveal that despite Australia’s risk assessment, INZ found Owens wasn’t at risk of inciting “harm” by its definition. The Free Speech Union (FSU) chief executive Jonathan Ayling and counsel Hannah Clow had stepped in as Owens’ lawyers to request special direction from associate immigration minister Chris Penk.

Three days after the FSU’s request to Penk in late November, the minister’s private secretary responded, and by the following week, the decision to deny Owens a New Zealand visa had been overturned.

‘The Australian community could be exposed to significant harm’

Owens first applied for an Entertainment Work Visa in New Zealand on September 9, two months out from a planned tour of Auckland in mid-November 2024, after advertising teased the commentator’s intended arrival. Ten days later, she submitted an application for an Australian visa for a tour happening the same month – though at the time, Burke had already hinted at his intention to halt Owens’ entry, telling the Sydney Morning Herald he hoped she “has a good refunds policy”.

On October 25, Owens received a statement of refusal from Burke which found that she had not passed Australia’s character test and was at risk of inspiring social dissension. The 23-page assessment undertaken by Burke, and released to The Spinoff as part of the OIA documents, considered Owens’ “profile as a political commentator, author and activist known for her controversial and conspiratorial views”, and provided 37 attachments – including news stories, interviews conducted by Owens (who is referred to throughout the documents by her married name Farmer), and her social media posts as evidence of views that ranged from “Holocaust denial” and “Islamophobia” to opposition of “women’s and LGBTQIA+ rights” and “anti-vaccination” views.

Assessing Owens’ risk of “inciting discord”, Burke referenced findings from the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation, Australian Federal Police and academic work which had shown a link between individuals who promote “rightwing extremism” online and a rise in “intent and capacity to undertaken [sic] violent acts”.

“I find that Ms Farmer uses various online platforms to spread misinformation and promote her controversial views and ideologies,” he wrote. “The evidence is clear. The use of platforms for inflammatory rhetoric can lead to increased hate crimes, radicalisation of individuals and heightened tensions in communities.”

Though Burke accepted Owens had not promoted “direct or overt violence”, he had “grave concern” that her views had been significant enough to influence the Christchurch mosque shooter, leading to the deaths of 51 people.

Burke had considered Owens’ right to freedom of speech and the issues of barring entry for an individual based on their rhetoric, however, he had decided the protection of the public to be of greater importance. Owens’ views could cause “serious harm to the social cohesion and fabric of the Australian community”, he wrote.

It took only a week for Owens’ Australian lawyers, Gillis Delaney, to criticise Burke’s “irreparable bias against Ms Farmer and her attempt to obtain a visa” in a letter to the National Character Consideration Centre sent on November 1 (they later took the matter to the Australian High Court on December 17). By that time, INZ was already considering the legal obligations which meant they would have to follow suit – though Australia’s threshold for assessing risks of social harm in potential visa-holders is far more rigid compared to what we have in Aotearoa.

‘They are emotionally invested and advocate for her decline’

Four days after receiving Burke’s letter, and 16 days out from her scheduled event at Auckland’s Trusts Arena on November 14, Owens made INZ aware that her Australian visa had been refused while she awaited advice from her Australian lawyers. INZ responded to her on November 1 with a letter citing potentially prejudicial information, which informed Owens her failure to promptly inform INZ about her cancelled Australian visa (which the department had learned of through media reporting), as well as the very fact that it had been declined, would now have effect on her visa application in Aotearoa.

INZ had received a report from its Risk Assessment Team the day prior, which found no evidence of Owens directly or explicitly advocating for harm or violence, though accepted that INZ had “no recorded definition of ‘harm’ that is relevant in this context”. NZ Police were also interested in Owens’ visa status – they had checked in with INZ on October 7, and were told the department had received her visa application. A member of NZ Police then followed up on November 4 following the news of her Australian visa being declined. “Has the position in NZ changed (or do you think she’ll forgo the visit here),” they asked.

On November 5, lawyers from Christchurch’s Duncan Cotterill – then representing Owens – challenged INZ’s November 1 letter to their client. They argued that, despite Burke’s letter, Owens was unsure of whether her Australia visa really had been declined, and whether the decision was lawful given Burke had hinted to the media that her application would be rejected before it was processed.

Meanwhile, the possibility of Owens’ visit to New Zealand had prompted backlash online and in the media from critics of her far-right views. In late October, Young Labour launched an open letter and petition calling for support to ban Owens, a “divisive force” who they said threatened the principles of the Treaty. Juliet Moses of the Jewish Council of NZ, meanwahile, condemned Owens’ “hateful, racist, historically illiterate and frankly stupid statements” in an interview with Newsroom, and Holocaust Centre chair Deborah Hart said there was “certainly a fear that her rhetoric could inflame tensions in this country”.

On November 6, just a week before it was due to take place, Owen’s speaking engagement was officially postponed, leading INZ to put a pause on assessing the visa. But by November 13, the pace had changed — a meeting scheduled the day after had been pulled forward, and INZ’s visa director Jock Gilroy was “being pushed to make a decision”, messages between staff members reveal. A final assessment completed by Gilroy on November 19 was shared with INZ and found Owens presented a risk, though the details of this have been redacted from the documents.

INZ had received a number of expressions of concern while considering Owens’ application, the messages reveal. “We are still receiving a good amount of public submissions regarding Owens’ travel,” read a Microsoft Teams message between INZ staffers November 13. “As you’d expect, they are emotionally invested and advocate for her decline. I expect these may die down over the next little while given other upcoming events taking centre stage in the media.”

On November 20, INZ informed Owens her visa had been declined under section 15(1)(f) of the Immigration Act 2009, in conjunction with Australia’s refusal under section 501(3)(a) of the Migrant Act 1958. The decision came out in the media on November 27, and that same day, FSU chief executive Ayling published a press release announcing the group had written to Penk and immigration minister Erica Stanford to condemn the decision, and calling for donations to help fund a legal battle against INZ.

It didn’t take long for the FSU to replace Duncan Cotterrill as Owens’ legal representatives. Two days after the FSU penned its complaint, the ministers received a new letter from the organisation asking for special direction to be granted for Owens, signed by Ayling and Clow as her lawyers. Ayling had been in touch with rightwing Australian commentator and Owens’ tour promoter Joel Jammal the day prior, to request permission to lodge an appeal to Penk – Jammal had sent their appeal letter to Burke to the FSU for inspiration, and told Ayling the minister’s “accusations” against Owens were “shaky to say the least”.

‘Get the point around free speech in’

The FSU’s request for special direction was processed on December 5, after Owens provided confirmation that Ayling and Clow were acting as her lawyers. A week later, two letters from Penk’s office were prepared for the lawyers – one declining special direction, the other granting it, neither with any reasoning to back up the decisions. As we now know, the following day, Ayling and Clow were sent the approval letter.

But before the lawyers received their approval, Penk’s staffers and INZ’s resolutions team prepared media lines. The original statement included a line that read “in considering this request the minister took into account the importance of freedom of expression”, which was later dropped, and then rephrased and re-added by a secretary in order to “get the point around free speech in”: “The minister made his decision after considering representations made to him, including the importance of free speech.”

Later that day, the FSU sent a newsletter to their members celebrating Owens’ win, and thanking the “pressure thousands of you put on the associate minister of immigration”. Ayling credited Penk for making “the only right call” and questioned what might happen to those in a similar situation who can’t “call the Free Speech Union in”.