Alex Casey reviews a cosy British biopic celebrating a groundbreaking moment in scientific history that many tried to erase.

What’s all this then?

A classic British underdog story that would sit nicely alongside Brassed Off, Made in Dagenham, and Kinky Boots, Joy charts the true story of the renegade research team who pioneered in vitro fertilisation, or IVF, in the 60s and 70s. From the producers of An Education and Brooklyn, and starring our own Thomasin McKenzie alongside James Norton and Bill Nighy, the film sheds light on the crucial moment that led to the world’s first “test-tube baby” who would pave the way for 12 million more.

What’s good?

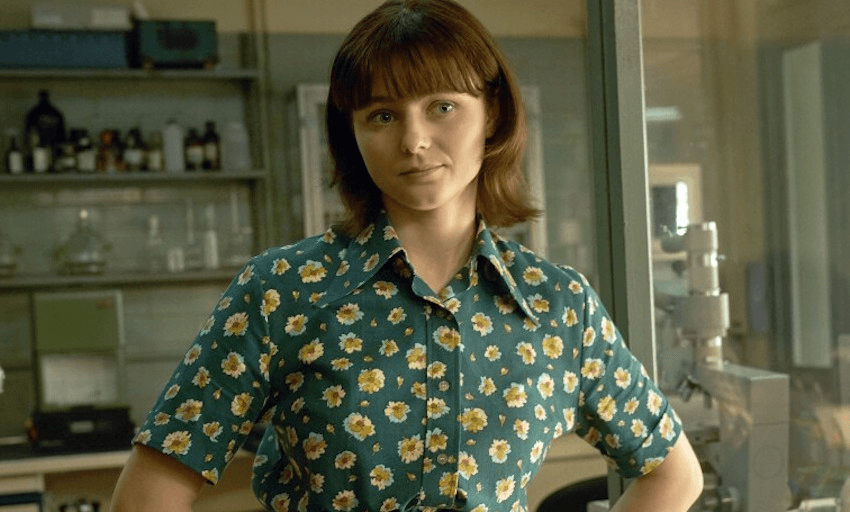

From her very first line – “bugger it” – it is clear that Thomasin McKenzie’s Jean Purdy is a character with a stronger injection of sass than previous roles we’ve seen her in. Prone to playing shy, waifish types, McKenzie is tremendous as the straigh-shooting nurse-turned-researcher who joins Norton and Nighy in their run-down laboratory. Her frank bedside manner (“no offence, but you don’t look happy to see us”, one patient says) also extends to her personal life: “If you promise not to become attached, we can have sex,” she tells a suitor that would, spoiler alert, get attached.

While it would have been easy to retrospectively drape Purdy in the platitudes of modern day yass-queen feminism and give her a mic drop Barbie monologue or two, the film isn’t afraid to reveal her complexities and conflicts as a woman from a conservative, god-fearing background during this era of huge social change. “I thought we were here to make babies, not take them away,” Purdy says when she discovers a secret abortion clinic operating next to their laboratory. “You are wrong: we are here to give women choice”, replies Matron Muriel, played by a steely yet warm Tanya Moodie.

Eventually ostracised by the church and her own mother for her role in the IVF experiments, Purdy is also revealed to have her own fertility issues – due to severe endometriosis, she has been told she can’t have children. “I’m not built to be a family woman,” she says, blinking away tears. It’s a reminder of the overwhelming pressure on women to become homemakers and mothers, a reality that seems both extremely dated and right around the corner at all times. To see endometriosis explored at all on screen, let alone so sensitively, feels like a watershed moment for a deeply misunderstood disease.

It’s also worth mentioning that the costuming, set design and makeup of Joy is brilliant. As the years tick by, the dusky pinks and mint greens of the 60s make way for the bold oranges and browns of the 70s. You can basically figure out what year it is by looking at McKenzie’s hair and makeup alone, as her Mary Quant fringe eventually morphs into a shaggy 70s bob. Still, any suggestion of vibrancy from the wardrobe and makeup is kept suitably British and understated by the film’s musty dark rooms, natural lighting and perpetually overcast grey skies.

What’s not-so-good?

While the film spends a lot of time detailing the pushback from the church, the media and the scientific community – “they are going to throw the book at us”, Nighy says at one point – the actual science they are dealing with is less clear. There’s a lot of mucking about with pee and pipettes and some stiff-upper-lip banter about bum injections, but I didn’t really get an impression of what the heck they were doing the whole time. Could Nighy simply fertilise an egg by… winking at it through a microscope? Perhaps.

Verdict: Even though you might not have a science degree by the end of it, Joy is a cosy British biopic celebrating a turning point in human history that many in the community tried to erase. McKenzie is the heart of the film, and should probably win a Nobel Prize for out-sassing Bill Nighy alone.