The scarcity of Covid-19 cases in New Zealand allows our formidable scientists to learn things you simply can’t in places where the virus is widespread. This helps us not just strengthen our controls but contribute to the world’s understanding.

The new community cases of Covid-19 in New Zealand remain a bit of a mystery. Fortunately, as of this morning there is no evidence of any further community spread. But, strange as it may at first glance seem, these cases offer an opportunity for the country’s public health and science systems to shine.

On Sunday we all groaned a collective sigh when it was announced that a family in Auckland had tested positive for Covid-19. A few hours later, Jacinda Ardern announced that Auckland would be moving to alert level three and the rest of the country to alert level two for three days to limit any further transmission while health officials gathered more information.

There were two reasons to be so cautious. The first was the worry that the family may be infected with one of the newer more infectious variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, a suspicion confirmed by genome sequencing results on Monday. The second reason was because, unlike our more recent community cases, the family aren’t directly linked to our managed isolation and quarantine system. None of the family work at a facility or had recently travelled back from overseas.

At the moment it’s a bit of a mystery how the family came into contact with the virus. We’ve got some leads, the biggest one being that one family member has a job handling laundry items from international flights. You might have heard some experts dismissing this as a possible source of transmission. As they’ve put it, despite the millions of confirmed cases globally, there are no documented cases of the virus spreading this way. And they are right. But just because it hasn’t been documented yet doesn’t mean it isn’t possible. It’s worth remembering that most of the almost 110 million confirmed cases are from countries with so much community transmission that they aren’t able to identify how people became infected.

As I’ve noted before, there’s at least one manuscript describing the SARS-CoV-2 virus has a half-life of between three and 20 hours on fabric made of 65% polyester and 35% cotton. That was a lab study where they contaminated different types of surfaces/materials and tested for viable virus rather than just the virus’s genetic material. The findings do suggest that virus could be present, for a short time at least, on fabric items used by infectious people.

There are some other possibilities for how the family became infected, one of which is that there may be some unknown transmission chains happening in the community and this family are just the tip of the iceberg. The sequencing data doesn’t strongly support this possibility at the moment, at least for managed isolation and quarantine being the source. But it is being explored as we don’t have any genomic information for any transiting passengers or international flight crew who may have passed through New Zealand while infectious. Again, all the more reason for us to have moved up the alert levels.

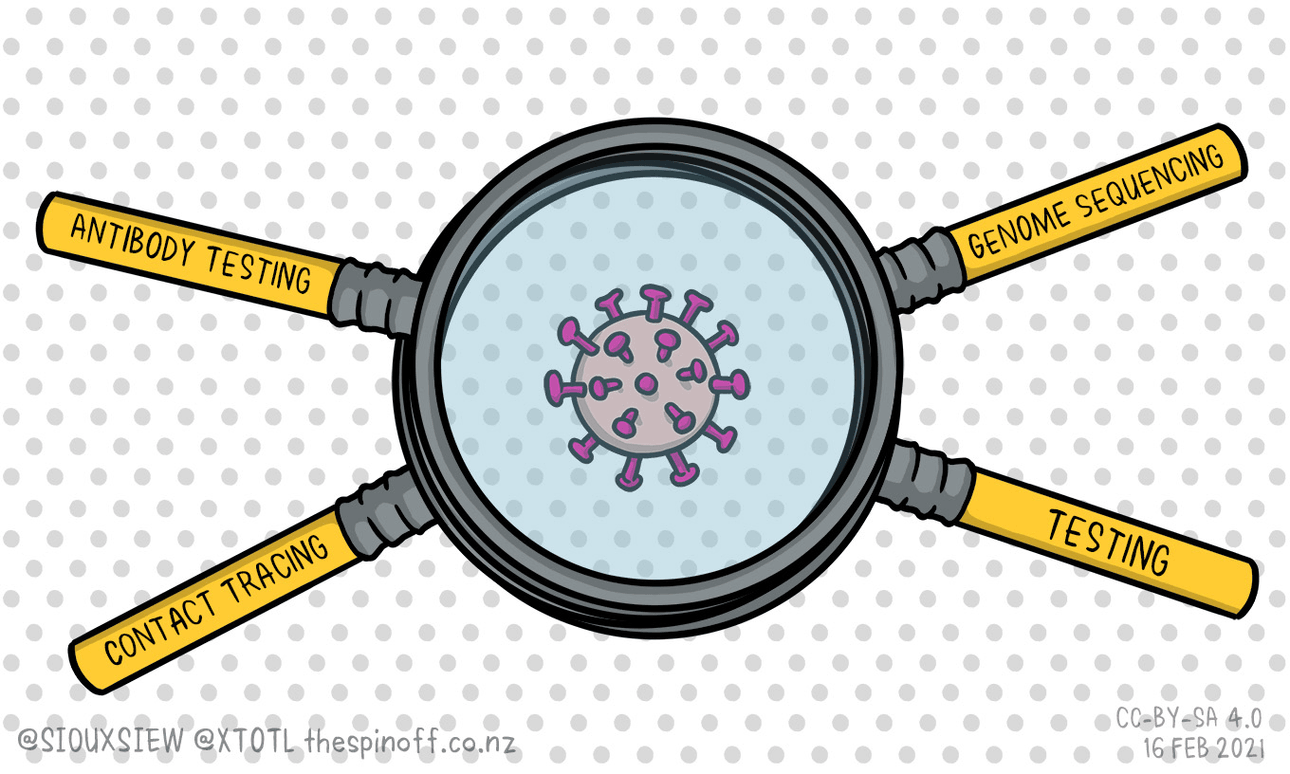

Right now, New Zealand is one of the few countries in the world with the ability to track down how people become infected with the Covid-19 virus. We’ve got ESR and our diagnostic labs able to test samples from people and the environment, including sewage, for any traces of the virus. Then we’ve got ESR and our diagnostic and university research lab’s able to sequence any viral genomes they can pull out of those samples. We’ve got ESR’s Dr Joep de Ligt and Dr Jemma Geoghegan of ESR/University of Otago and their teams to make sense of those genomes for us. We’ve got our incredible contact tracing teams within the different public health units trying to track down where any people who test positive have been and when, and who they’ve been in contact with, all helped by us using the Covid Tracer App and scanning QR codes wherever we go. And finally, we’ve got the University of Auckland’s Associate Professor Nikki Moreland and her team who helped establish the serology tests being used to rule out any positive test results that are caused by people having been infected in the past (so-called historical infections). And of course, the public health labs doing that serology testing.

It’s this incredible team effort that gives us the best chance of getting to the bottom of our mystery cases. And when they do, they’ll be able to document what they found for the rest of the world to learn from. Just like they did to show how transmission can happen on a long-haul flight. I’ve written about that study led by Jemma and Tara Swadi from the Ministry of Health here. Their work is an excellent example of how we not only learn all we can from every case to strengthen our controls but contribute to the world’s understanding of Covid-19.