Over the past two years we’ve become accustomed to using the daily case numbers to track the success or failure of our Covid response. But the biggest number isn’t necessarily the most important, writes Siouxsie Wiles.

It’ll soon be two years since the World Health Organisation declared Covid-19 a pandemic. In that time, we’ve seen a multitude of clinical trials identify which of our existing medicines can help treat people with the disease, alongside the development of safe and effective vaccines and Covid-specific anti-viral medicines. Covid-19 is still deadly for some of those who get it, but if you are boosted and live somewhere with good access to healthcare, chances are you will get now through at least the initial stages of a Covid-19 infection relatively unscathed. As for the long-term consequences of infection, it’s still too soon to tell.

But inequitable access to vaccines and medicines, as well as the “let it rip” approach pushed by the Covid Plan B and Great Barrington Declaration proponents, means more dangerous variants of the virus have emerged. Alpha. Beta. Delta. Gamma. Theta. Epsilon. And now omicron. To complicate matters further, there are several different versions of omicron circulating.

So, what do we know about omicron? It’s almost three months to the day since South Africa announced that its state-of-the-art genomic sequencing efforts had detected a worrying new variant – one that spread from person to person very quickly and was much better at infecting people who had previously had Covid or been vaccinated. Since then, data from multiple countries has shown that the risk of people infected with omicron being hospitalised is a third to half that of people infected with delta. Here’s the data for Denmark, Scotland, and the UK.

I said that there are several different versions of omicron circulating. So far most of the data we have relates to the BA.1 version. Another of relevance to New Zealand is BA.2. While BA.1 and BA.2 are part of the same family tree of the virus, they are quite different to each other in terms of which mutations they have. In some countries BA.2 is now starting to become the dominant strain so hopefully we’ll know a little more about it in the coming months. In the meantime, data from Denmark and the UK suggests that BA.2 is more transmissible than BA.1. See the WHO’s summary of the data here. A new preprint study by Japanese researchers also reports that BA.2 grows better in human nasal cells in the lab and reached higher numbers and caused worse symptoms in hamsters than BA.1. People aren’t hamsters, obviously, so it remains to be seen how this translates to humans.

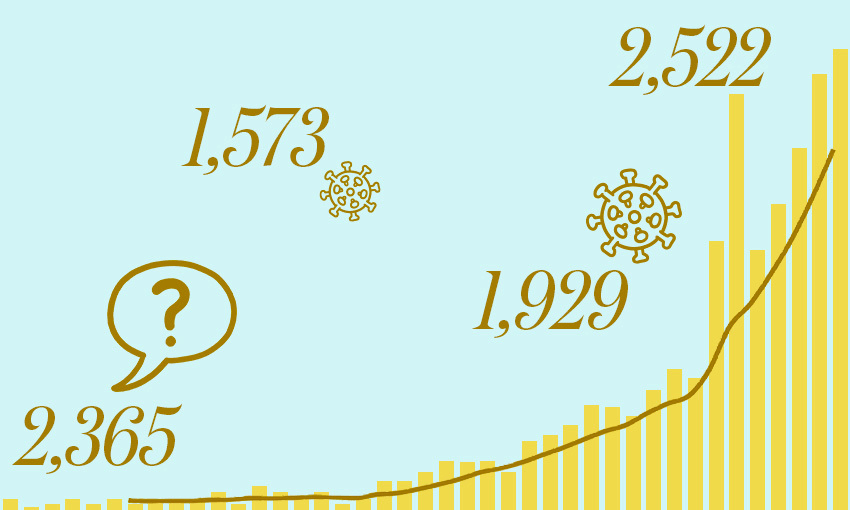

Globally, omicron is driving daily case numbers well beyond anything we’ve seen so far in the pandemic. While it took the world about a year to reach its first 75 million confirmed cases, there have been nearly as many just in the last 28 days. Here in New Zealand, our outbreak is growing exponentially. We currently have delta, BA.1 and BA.2 circulating in the community. Our initial omicron cases were caused by BA.1 but BA.2 has also been introduced and made its way to the Soundsplash festival in Hamilton. It’s likely delta, BA.1 and BA.2 are present in different proportions in different parts of the country, and possibly within different communities. You can see how they stack up against each other as a proportion of sequenced cases here. A word of warning though, the data on that site isn’t completely up to date.

The Ministry of Health reports lots of different numbers to describe what’s happening with the outbreak here. Let’s look at what some of them mean.

Confirmed daily cases

This is the big headline number and it’s the one that’s currently higher than we’ve ever experienced here in New Zealand. It’s the daily measure of how many people have tested positive and so caught the virus anywhere up to two weeks ago, though probably mostly in the last week. Like almost everywhere else in the world, the number of confirmed cases will be an underestimate. Data from overseas suggests the real number of infections could be four to five times higher. There are lots of reasons for this discrepancy. One is that it depends on people going and getting tested and another is that it depends on testing capacity. Data from South Africa also suggests that nasal swabs may miss one in 10 positive omicron cases compared to swabbing someone’s throat or testing saliva instead.

In terms of people getting tested, not everyone who has symptoms will go and get tested. Testing levels also fluctuate over the week, dropping over weekends and public holidays. For this reason, it’s often best to follow the seven-day rolling average for daily cases instead as it smooths out these ups and downs. As for testing capacity, up until now, we’ve mostly been reliant on PCR testing which is very sensitive but takes time and our labs can only run a certain number of samples per day. While capacity has been ramped up, it isn’t infinite and that’s why, as the outbreak grows, rapid antigen tests are being added to the toolkit. These aren’t quite as sensitive in the very early days of an infection so you’re more likely to be given a rapid antigen test if you’ve got symptoms rather than if you are a close contact who has been asked to get tested but doesn’t have any symptoms.

Depending on the trajectory our outbreak takes, we could see tens of thousands of confirmed cases a day over the next few weeks.

Positivity rate

The positivity rate is the number of tests that come back positive and reflects whether a country is testing widely enough to catch all cases. Like the number of confirmed cases, the positivity rate is also influenced by things like testing capacity. A high positivity rate means the confirmed cases likely represent just a small fraction of the real number of infections, and a rising positivity rate can suggest an outbreak is growing faster than the growth seen in confirmed cases.

In 2020, the WHO suggested that a positivity rate of less than 5% is one indicator that can be used to suggest Covid-19 is under control in a country. For much of the pandemic, New Zealand’s positivity rate has been well below 1%. But the rate has been rising over the last few weeks. It took a month for Australia’s seven-day rolling average to go from the level we’re at to its peak of over 40%.

Hospitalisations

With delta and omicron circulating in New Zealand, the majority of us who have had our booster shot should come out of the experience relatively unscathed, at least in the short term. The data from overseas shows that three doses of the Pfizer vaccine prevent many people from having symptomatic Covid or ending up being hospitalised and that holds for both delta and omicron. As I said before, it’s too early to say whether the vaccines also protect against any long-term consequences of infection.

While we’ve had really high vaccine uptake here in New Zealand, there are still plenty of people who haven’t yet had their booster dose. The data is really clear that it shouldn’t be considered an optional extra. We also mustn’t forget that as well as the people who’ve chosen not to be vaccinated, we still have all our under-fives who can’t yet be vaccinated, and our under 12s who are still in the process of being vaccinated. There are also people who have an underlying health condition that leaves them less protected by vaccination. We’ll see how these people are faring in the hospitalisation numbers. Remember, we still have delta circulating and that has a higher hospitalisation rate compared to omicron.

Cases in ICU/HDU

As of February 14, Medsafe was still waiting on data from Pfizer in order to complete its assessment of Paxlovid, the antiviral agent that has been found to be very effective at keeping high risk people out of hospital and from dying of Covid-19. Without this medicine, we should expect more people to need this level of hospital care as cases rise.

Deaths

The last number to watch is deaths. Thanks to following an elimination strategy, we’ve had one of the lowest death rates from Covid-19. If everyone eligible gets their booster shot, we’ll hopefully be able to keep our death rate low. But not everyone has, so we’ll see more deaths. We also don’t have access to anti-virals like Paxlovid which would help.

It can take days to weeks for people to get sick enough to need hospital treatment, so hospitalisations and ICU/HDU numbers generally lag behind daily case numbers. But they are numbers we have to watch closely. We don’t have an unlimited number of hospital beds or medical staff to care for people. People also don’t stop having babies, or heart attacks, or strokes, or car accidents, or cancer, or needing dialysis or surgery. The higher our number of Covid hospitalisations, the less capacity our already stretched health care system will have to deal with everything else it normally deals with. We’ve seen this play out overseas, with rapid increases in case numbers leaving hospitals struggling to cope with Covid patients and having to put other important medical procedures on hold.

The numbers to watch

So, which of the numbers should we be paying the most attention to? Personally, I think they are all important though useful in different ways. I’m watching the seven-day rolling average of the daily cases together with the positivity rate to track whether the outbreak is still growing and how much bigger it might be than the daily case numbers suggest. That’s important information if you are trying to manage your risk of being exposed. If you or someone you live with is at a higher risk of severe disease, you’ll likely want to limit the more risky activities during the peak of the outbreak.

The numbers the government and health officials are going to be paying the most attention to are the hospitalisations and people in ICU/HDU. Those are more accurate and will determine the capacity of our healthcare system and whether things like elective surgeries need to be put on hold. Saying that, everyone will want to watch those numbers as they’ll impact our ability to get care if anything happens to us.

I guess we’ll soon see how good our vaccination rates and the red setting of the traffic light system is at stopping our hospitals from being overwhelmed. But the fact we are only at the beginning of this wave means it is premature and dangerous to be talking about lifting any of our public health measures right now. And that’s without the occupation outside parliament and all the other demonstrations against our public health measures. Given what I’ve seen of the protests, I think it’s safe to assume many of the protesters are unvaccinated. It feels like it’s only a matter of time before they are going to experience the disease some of them don’t even believe exists. When that happens, they’re likely to have an outsized impact on our hospitalisations and deaths.