I try to imagine turning up to a party with a new nose. I think it would be embarrassing. My nose would be saying: ‘Yes, I was $10,000 worth of insecure.’

The Sunday Essay is made possible thanks to the support of Creative New Zealand

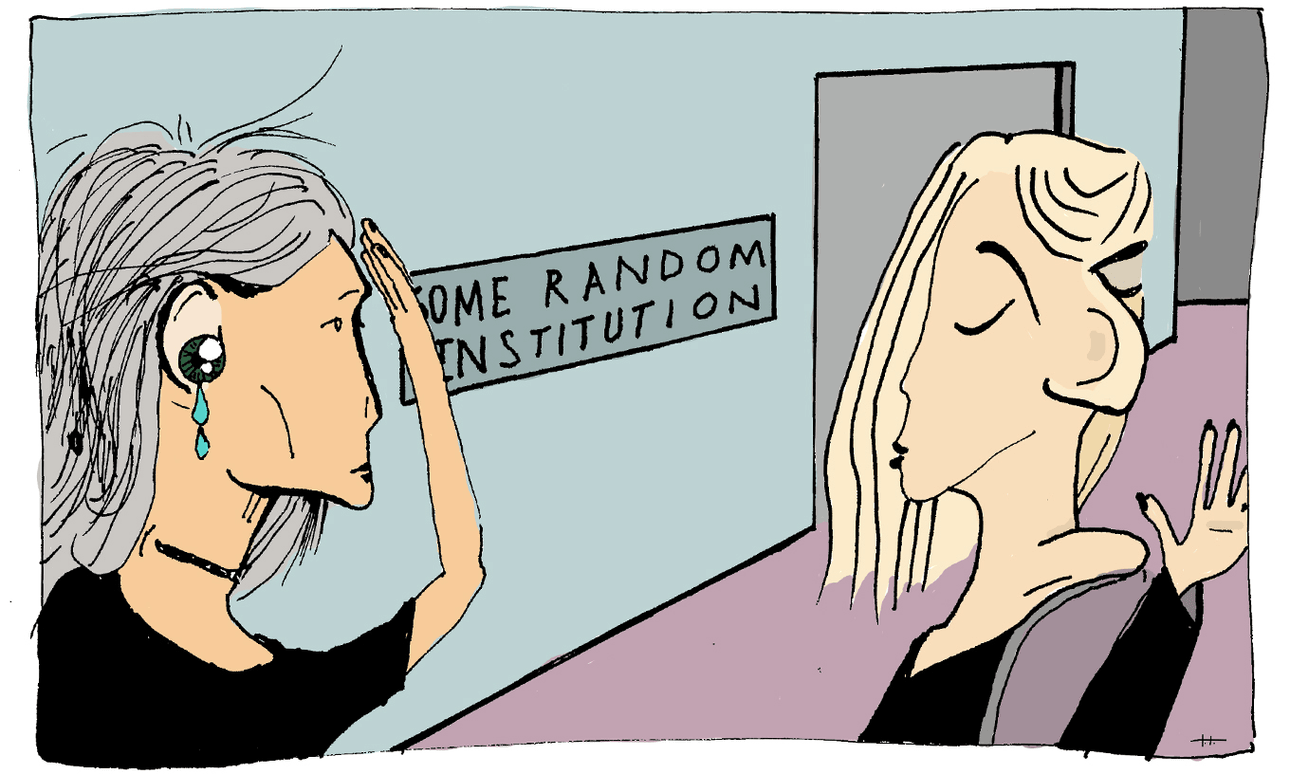

Original illustrations by Tom Tuke

I hold my arm straight out in front of me, as still as it can be. I try to catch the light on my cheeks, widen my eyes, and not smile but smile at the same time. I am semi reclined on my couch but pulling up my chins. My thumb presses onto the smear at the bottom of my phone screen.

I sit up, bring the screen closer, inspect. It’s not good.

My nose veers to the left. This is not acceptable content for a single lady in 2021.

When my mum was 18 she sold crocheted handbags on the pavements of Buenos Aires, her hometown, to save up for a nose job. She went to a surgeon who was cheap because he didn’t do the procedure at a hospital, but rather, a place she would later describe as “some random institution”.

In doing so, he bypassed expensive things like regulations.

He performed the surgery not under general anaesthetic, but local, which is to say my mum was awake and lucid. He gave her two Xanax pills and a few numbing injections around her face. She remained conscious.

“I remember it,” she told me, 43 years later. “I remember lying there.” She stood in the hard-edged kitchen she’d renovated only a couple of years earlier, in the house my parents had considered central because from one of the first storey windows they could see the needle-point of the Sky Tower. She was so skinny, for the first time smaller than me. We had just cleared out all the drawers and cupboards into apple boxes. The drawers had tiny hydraulic pistons to stop them from slamming – she called them “soft close”. These pistons were the final detail of the proud, beige renovations which felt like a labyrinth of handleless, quiet cabinetry, everything important hid inside. She decided not to keep any of it – taking the apple boxes of plates, glasses and cutlery to the op shop the next day.

In the kitchen she made banging and sawing actions with her arms – elbows upwards, directing jolting and repetitive movements towards her own face. She stopped and gathered her breath.

“At the time, when I was 18, I thought it was the best thing I could do to my face, to be beautiful. Now I think, well, maybe I should have gone to a psychologist.”

I wanted to agree. But being beautiful has many social and economic advantages in life. It is easier to move through the world if you are beautiful. People like you more and it’s easier to get jobs. These aren’t the things you’re meant to think as a feminist, even though they are the things you know.

I can’t say what her life would have been like with her nose-of-birth, but I can say she readily fits beauty standards with her new, chosen nose. She came to New Zealand with incomplete English, which fumbles on her tongue decades later. Even now I help her with job applications, editing her CV, re-writing her cover letters. Life probably would be even harder for an immigrant woman with a huge nose, rather than a pretty one.

Her chosen nose is unspectacular. She didn’t want the tiny 80s ski slope nose “everybody else was getting”, she wanted to look as though she hadn’t had surgery, for her beauty to seem natural and be believable.

“It was quite cheap back then,” she told me. In Buenos Aires it remains a popular and normalised procedure.

Every year my reflections, my photos, look more like my mum. When we visit Buenos Aires, every couple of years, older family members tell me, “You look so much like your mum.”

I ask, “Pre or post nose job?”

They don’t love this question.

Perhaps if I change the lighting. I move to the other couch, its upholstery is coming loose, but it faces the only window. The light diffuses across my face.

Repeat.

Inspect.

Hmmm.

The veer is still apparent. In addition, my eyes look crazed. I am still trying to learn the selfie, at almost 30, because my younger flatmate said thirst-traps are an essential social technique for this era. I tilt my head.

Repeat.

Inspect.

It still veers.

Once a portrait of my face won my ex-boyfriend £7,000. I’m aware it sounds romantic at first, perhaps Titanic-esque, but it really wasn’t. It is not a pretty or flattering portrait, as I so desperately wanted. My eyes aren’t even open. He put grey in my hair before I had any. The reference photograph for the painting was taken in the leafy backyard of his parents’ inner-city villa. Their house didn’t have the elevation for a view, but when I walked up the street, I could see the Sky Tower almost in full. We were there often, because we lived nearby and didn’t have our own garden. He never wanted to drive the 20 minutes to visit my parents, and even though I had paid for half of our car, he wouldn’t let me drive it.

Of the series of photos he took, in which I tried to have cheekbones and sultry eyes with a sparkle in them, he chose an in-between photo to paint from, when the flash went off unexpectedly and forced my face backwards into my neck and my eyes into a crumple. At first we laughed at this photo: it had captured me, the way I make strange faces a lot, talking with my face instead of my mouth. I asked him not to paint it.

In the portrait, he exaggerated the slant of my nose, and painted me in violent, quick strokes, reducing my face to a series of slightly green creamy facets fighting with each other.

I thought nothing would come of this small painting, but he entered it in an annual portraiture competition sponsored by exploitative oil spillers. When it was announced as a finalist, an overpriced box was made for the painting and it was sent to be judged and exhibited at the National Portrait Gallery in London. It won the Young Artist Award, a paltry feat the New Zealand media loved. Articles, with a photo of the painting of the photo, made their rounds through social media. I didn’t allow the tagged images or posts to appear on my profile. I silently wondered if my boyfriend had been the only artist under 30 to enter the competition for such an outdated art practice.

He didn’t share the prize money, and I got tired of paying for half the groceries even though I hardly ate and his appetite was bottomless. So I left. A couple of years later, I was trying to be a supportive ex, so I went to his art show. He must not have thought I’d come. On the wall was that face of mine, contorted into its worst features, stripped back into the flicking action of his brush. I saw my mother’s face, taken from me, slapped on a canvas by a white cis man and then profited from.

A lot of people were crowded around the painting because it was “famous” and people are stupid. I decided to have as much free wine as possible. On my way home, I sent him a drunk and bitter message about privilege, permission and respect. He didn’t reply. Four years later, the painting is still on his website.

I go to the bathroom, where mould seeps down from the corners. I have to wipe the mirror. I turn my head slightly right, and slightly left. I am almost cross eyed, staring into the central feature of my face.

I think maybe if I take the photo through the mirror, optics and light rays will flatten my nose and straighten it.

Repeat.

Inspect.

I am wrong.

I come from a line of big-nosed women who find themselves single later in life. Men were once lost to early death, or younger women. Now we choose to lose them to our own independence, widening horizons, our own spaces and schedules. So we empty the cupboards, and give all the cutlery, all the glasses and all the plates to the op shop.

My grandma probably has the biggest nose I’ve ever seen on anybody. It is bony and protruding, its bridge arching forwards from the centre of her face. In my memories it leads her around her third storey apartment in Buenos Aires. The elevator shaft cuts through the centre of her apartment, so that it is structured around an empty space. This void is enclosed with a tiled hallway, which she is always clattering around, nose-first around its four corners. I could probably fit three fingers, flat and side by side, in each of her nostrils. Her nose has a dark, bulbous mole on one side, I forget which.

She clothed her four big-nosed daughters by trickling clothes downwards. All garments were forced to have four lives. Although my mother was not the youngest, she was the smallest, so she got all the clothes last, after they had already died three times. She still insists this was unfair.

I always wanted my sister’s clothes. She seems a hazy figure in my youth. Eight years my senior and perpetually the cool teenager, then adult, always less tied to the family. I would sneak into her room when she was at her friends’ houses to try on her black mesh top with the silver glitter butterfly across its front, or her halterneck with the pink rose print. I’d pull open her underwear drawer, and hook bras around my childish frame, stuffing the cups with her socks. My sister’s nose is elegantly pointed and slightly hooked, its tip pulling downwards when she smiles. Mine is a skewed triangle with a bubble of cartilage fastening nostrils to its tip. Her nose is straight.

From the bathroom I hear my flatmate – small-nosed, blonde, voluptuous – rustling in the kitchen. An excellent target for my superficiality.

She tells me, “It’s a Roman nose, and I appreciate classical beauty.”

But at almost 30, I really do wish I was contemporary.

I return to the mirror. It seems no matter how far I angle my face to the right, its central feature always points off to the left.

Repeat.

Inspect.

The most beautiful thing a face can possess is symmetry. I remember this from an article about Brad Pitt. His face is strikingly symmetrical, and he is, of course, endlessly beautiful.

Repeat.

Inspect.

Well, shit.

I am less diligent than my mum: the violence I have inflicted on my own face has been out of clumsiness.

When I was six, or seven, I played too long at morning tea break. My friend, who was so much taller and stronger than me, would pick me up by the armpits and spin me around and around in the sunlight. She spun me beyond the bell, and so, I had to run back to class. Instead I ran into class. The doorway shifted, suddenly it was in my face.

When my mum picked me up from the sick bay, I was sticky with blood and the nurse’s reassurances. After my nose healed, she took me to a male doctor who inspected it. He commented on the new bump on its bridge, considered it straight enough, and said it wouldn’t be anything I got teased about. He didn’t predict Instagram, Tinder and selfies.

After this breakage, I was susceptible to nosebleeds. I’ve never really known if it was the injury or my deep interest in excavating it. I can at least say I never ate its contents, although I pulled them, pressed them, rolled them, and stored them for safekeeping and further inspection.

One nose bleed happened at intermediate school, in PE. I think it was the same year someone hit me in the mouth with a baseball bat.

Contorted into a grade-based school curriculum, PE pushed us into all sorts of unhelpful, body-shaming assessments. There was the timed cross country, the barred high jump, the measured long jump, the period we spent weighing and measuring each other to determine BMIs, and the demonic beep test. You would think people run to get somewhere fast, or maybe to enjoy fresh air and some scenery quickly, but the beep test incorporated none of these acceptable applications of running. We were herded into a line across the wall of the sticky gym, and our blonde (of course), tanned (of course), muscly (of course) gym teacher turned on a portable tape player, which proceeded to snort out beeps with ever-increasing speed. We had to run backwards and forwards to each end of the gym before each beep, our shoes squeaking. In the first period we were subject to this, I ran across three times before deciding it was dumb and walking to the foyer to wait it out. The next day, blonde-tan muscly teacher told me she would fail me if I didn’t try. I ran until my nose bled.

Repeat.

Inspect.

I realise a photo can only really capture what’s there. A Google search tells me nose jobs in New Zealand cost upwards of $10,000. I’m not going to be able to make $10,000 with crochet.

I try to imagine turning up to a party with a new nose. I think it would be embarrassing. My nose would be saying, “Yes, I was $10,000 worth of insecure.”

And so, the wonk gets uploaded to my Instagram story. I’ve opened my mouth slightly, so the babes know I’m thirsty.

My mother didn’t tell her mother she was having a nose job. She just came home in bandages after the procedure.

The only photo my mother has shown me of her youth is smaller than the ones I am used to, and has rounded corners. It is a full-colour film photo, but apart from the soft blue sky, everything is a sepia-infused tone of brown, or grey, or peach. In it she stands alongside her three sisters and mother in Mar del Plata, a beach close to Buenos Aires. They face the camera and the sun, in one piece togs, their shadows falling behind them. My mum looks about 13 years old, and she is the skinniest of the group. Her eyes are in shadow, while the bridge of her nose catches the sun, like her mother’s and sisters’ bridges. Their smiles sit proudly in the shadows of their noses.

I often marvel at my grandmother’s nose. How did she make it through life with all of that on her face without breaking it? She must never have gone inside a mosh pit, fallen off a bike, never been as clumsy as me.

My grandmother’s fingers are long and bony, echoing her nose. We used to sit at her Formica kitchen table, our knees knocking together, and she’d tell me about her piano playing, while jolting her red pointed fingernails across its surface.

She had been a good player; nimble, precise, and emotive.

The only time I have heard my grandmother mention the nose job, she referred to it as “el horror” my mum inflicted on her own face. Her lips were tight, her heart, I think, contracted. I think all she can think of is my mother’s swollen, bruised face when she came home that day.

I too came home one day without warning. It had been eight years since I moved out of home. I had boxes and bags instead of bandages. The car I wasn’t allowed to drive was stuffed with my clothes and books. The portrait painter was practising kickboxing at the gym.

“What happened?” my mum asked me.

That evening, I was sitting at the kitchen bench, drinking chamomile tea. It was a year or so before my parents renovated, but already the lights were too bright, rendering what was outside the windows black. The cabinetry was the same blonde wood veneer with fake bevelling and rounded handles I had thought was pretty as a child. My dad would get so angry when he heard the cupboard doors or drawers bang shut. When he was home we pushed them slowly, guiding them right up until they were closed so that they were silent. We had to rub our oiled finger prints off their edges. He was in bed now, probably reading.

My mother joined me, with the dark chocolate block that seemed to materialise each night. She wanted to know if I thought we could get the painting. “I know you don’t like it,” she said, “but I really think he captured you.” The painting was still in London, and had a price tag of $20,000.

“We can’t afford it, Mum.”

I slept in the room with the view of the Sky Tower’s point.

It was the same room my mother slept in the night I helped her empty the contents of the new, soft close cabinetry into apple boxes.

My screen lights up. My sister has replied to my Instagram thirst-trap. “Wow, you look like Mum.”