Welding is usually more associated with a garage than a gallery, but artist Yona Lee learned the trade to put together her epic sculptures that blur the boundaries between inside and outside, and public and private space.

“We like to categorise. We like to divide… But I’m interested in thinking about the similarities we share between spaces – between people – and making that more important than the differences.”

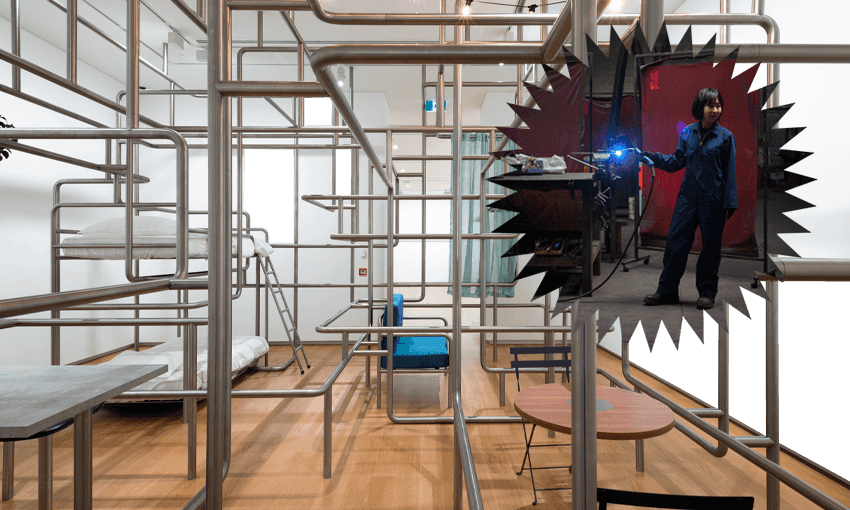

Yona Lee’s current exhibition at Toi o Tāmaki is a sight to behold. Its epic scale takes it over five rooms, and even bursts beyond them to Albert Park outside. Walking through the exhibit, it’s immediately apparent what Lee means when she talks about breaking down the boundaries between spaces. Although the exhibit is entitled An Arrangement for 5 Rooms, Lee’s work makes the rooms appear as one. The steel tubing commonly used in public spaces snakes almost unbroken through the space, joining the exhibit together so that it almost becomes one massive sculpture.

The steel tubing blurs the boundaries between inside and outside, and public and private space. In the first room, a singular street lamp is connected to a handrail too high for the average person to reach. By being placed so high up and running across doorways overhead, the rail defies its intended use. Halfway across the room, the railing narrows to house a white towel and a bathmat, ready for use. A few rooms over, a singular dish of soap is similarly placed overhead above a bus seat.

Lee’s work both condenses and explodes space. Elements of a bathroom – shower curtains, towels, soap – are smeared across the exhibit. Downstairs, an innocuous stair-rail ends in a defiant mop-head which protrudes up toward the ceiling. The domestic – a kitchen counter, hanging pot-plants and couches – suddenly merge with the public – bus seats, cafe tables, overhead handles. Walking through the exhibit feels like a dreamworld, simultaneously disorientating and familiar. By playing with space, Lee also plays with time – in the sculpture I recognise my morning commute, my afternoon coffee, the kitchen counter where I make dinner.

Lee’s exhibit is interactive, too. The steel tubing at various times becomes couches, tables and bed frames. The exhibit is at once empty and crowded, with some rooms appearing stark and barren, and one room almost completely filled with steel piping that forces visitors to retrace steps, wind around objects and step over steel kerbs. A couch with a fan in front of it invites visitors to relax. A museum worker sits at a cafe table with a book in hand. I plug my laptop into a powerboard and discover with delight that it’s functional.

With an exhibit this interactive, visitors almost become a part of Lee’s sculpture. And that’s just how she means it to be. Lee comes from a performance background, with training as a cellist: “I’d take lessons and participate in orchestra, I’d be playing in chambers and always practising for concert competitions. It was quite full on. I thought I would be a cellist.” But life had other plans for Lee, who says she never thought she’d be an artist. “It just sort of happened,” she laughs. But Lee hasn’t forgotten her cellist roots, and it shows in her artistic practice.

“When you perform, every performance is new. Even if you repeat the same song you’re responding to the audience, the space, and how you’re feeling at the time. Everything is so site specific.

“I want to have a show that’s special for the space, so that the space becomes part of the work.”

Lee describes her work as being “in conversation” with its surroundings. Not only is her work in conversation with the space at Toi o Tāmaki, at times mirroring the steel supports of walls behind it, or else framing trees through the windows, it’s also in conversation with people.

The pandemic has emphasised borders and divisions, notes Lee. “With having these borders, you suddenly realise there’s a line, there’s a division there. With my work, I bring all these objects that signify different places, and for me this is a way to connect these places.

“There’s no division, there’s no characterisation… they’re all intertwined.”

Lee points out that this division doesn’t just characterise space – it also characterises how we think of ourselves. Ethnicity and gender are just a few examples of how we categorise people, she notes. Fittingly, Lee’s work doesn’t just conceptualise the breakdown of divisions, it also enacts it. Over the years, she has learnt to weld her sculptures herself. Although some of her previous work was welded by others, the current exhibition was installed by Lee, and she notes it can be challenging to work in a male-dominated environment such as metal-working.

“People don’t take you seriously or they’ll make stupid jokes because you’re a young female… even now you go to the workshops and they’ll still have those calendars with the naked girls on them!”

Lee laughs that many people have been surprised by her work: “People would always comment, ‘oh my god, you’re so small, you’re so fragile’… just the fact that they notice it and then talk about it interests me.” But although some have been condescending, more have been helpful, and Lee cites another woman welder as being one of her greatest helps and inspirations.

It’s ironic too, that welding is associated with the masculine, says Lee, as most of the machines do the heavy lifting. “These bigger-scale sculptures, they’re about understanding, about building a system… I bring a feminist view on this material. I believe my work has a very different connotation to more ‘male’ metal structures.” Seeing her work, I’d agree – Lee’s work has a distinct focus on the domestic, and the whimsy of the structures expand the steel beams beyond the practical and into the abstract.

Lee says there’s a reason she’s drawn to steel: “It’s quite strong, it’s got an architectural quality. And at the same time it’s quite malleable.” She notes that because her work is so durable, it can exist beyond the limitations that more traditional art might be subject to – her sculptures don’t need light or humidity control. These sculptures live in the spaces we do, not just in museums and galleries.

Currently, Lee is in Maastricht in the Netherlands, completing the Jan van Eyck Academie Residency, where her next work will be installed on the outside of the building. Like all her projects, it’s ambitious and thoughtful – Lee says she’s looking to respond to conversations happening locally about decolonising art practice.

But even as she works on new installations, Lee notes that the installation back home in Aotearoa is “really important for me, conceptually and work-wise”. She hopes that people will enjoy the exhibit and get out there to support galleries and artists post-Covid. Lee says that although she’s put on many shows and created work in many places, “[art] is definitely a field where there’s no security.

“I see a show I do, and it could be my last show. There’s no guarantee, and I think it’s the same for everyone.”

An Arrangement for 5 Rooms is on at Toi o Tāmaki – Auckland Art Gallery from now until August 28 and she appears in ASIA: Art Stories In Aotearoa on RNZ.