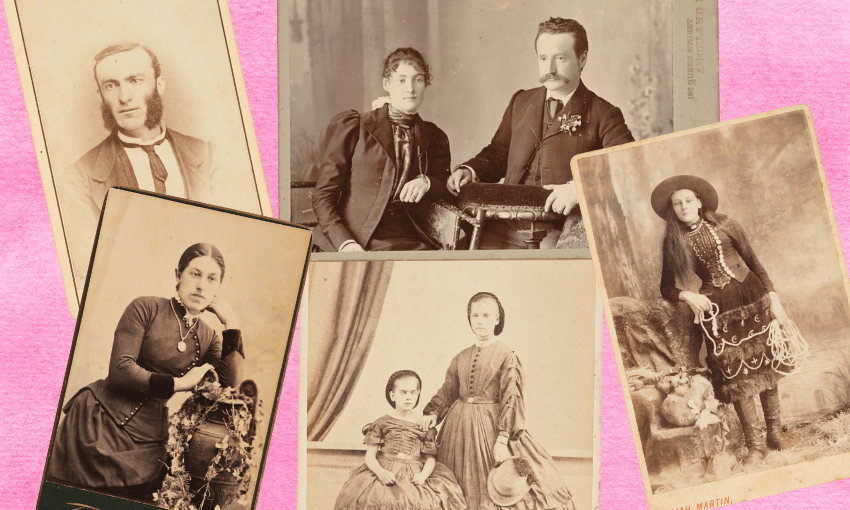

Some of the earliest photos of life in Aotearoa are on display at Auckland Museum right now – but the identities of some of the people in them are a mystery.

What was it like to be one of the first people in New Zealand to have their photo taken? In a word, “awkward”, says Shaun Higgins, pictorial curator at Auckland Museum. He saw plenty of wooden poses and bewildered expressions while putting together A Different Light, an exhibition of some of this country’s earliest photography.

The oldest photos in the collection are daguerreotypes dating back to the 1850s, which would have required subjects to hold still for somewhere up to 45 seconds. This meant candid smiles or indeed any facial expression other than a steely gaze was largely out of the question. “They weren’t necessarily all miserable,” Higgins says, “though they quite often look like that.”

Higgins teamed up with curators from Wellington’s Alexander Turnbull Library and the Hocken Collection in Dunedin to put together the exhibition, with their combined collections offering a “vast pool” of photography from around the country to choose from. But rather than simply picking out the best, most spectacular images of Aotearoa in the 19th century, he says they wanted to let audiences see some of the more “everyday” material.

The result: lots of portraits of everyday people who likely never imagined they’d end up on display in a museum, and whose heads probably would have fallen off if you’d tried explaining “The Spinoff” to them.

And yet, here they are. These are some of the people featured in the exhibition that the museum has little to no information on, and wants to find out more about.

Admittedly it’s a long shot that a Spinoff reader in 2024 would recognise someone in a photo from the 1870s, but it wouldn’t be entirely unprecedented. Recently a museum visitor IDed their ancestors in a family photo that was on display, despite the photographer having got their name wrong. “It was wonderful,” says Higgins, who was then able to track down another photo of a different family member for them.

You can get a lot of information out of a photo if you know what you’re looking for, and Higgins knows just about every trick in the book. For really old photos the first thing he inspects is the cases they come in, and can usually narrow it down to within a couple of years from when a particular type of case was in use. “It doesn’t always mean that the picture itself was taken at that time, but it gives you a start.”

From there he inspects the photograph itself. He can tell at a glance what kind of technology was used (“daguerreotypes were used from 1848, for example, and then they shifted to the ambrotype…”) – and with the pace at which photography evolved in the 19th century, that usually narrows it down quite a bit too.

But often the best information is found on the other side. “It’s funny,” Higgins says, “on one hand it’s very bad to write on a photograph – over time it can bleed through and damage it. But on the other hand, often the writing on the photographs is how we find out more – a name, a number that a photographer’s used, a message written for a family member… all clues to investigate.”

Higgins’ forensic analysis leads him down some extremely niche wormholes. “I love looking at props or details like tablecloths,” he says. “If somebody’s sitting next to a table, I can sometimes nail the tablecloth down to a specific studio.”

The least reliable part of the photograph tends to be the subject themselves. You can’t read too much into the clothes people are wearing, Higgins warns – studios often provided costumes for people to wear, and if not they’d at least have got dressed up in their Sunday best.

A Different Light charts what Higgins describes as the “democratisation” of photography through the 19th century. The first daguerreotypes would have been prohibitively expensive – he estimates somewhere in the region of $500 in today’s money – but towards the end of the century cameras became more accessible, meaning more and more people could start documenting their own lives, while it also became more affordable to visit a portrait studio.

One of the things Higgins enjoyed the most while putting the exhibition together was seeing the ways people found to express themselves despite the technological restrictions. “One of my favourites is a very big daguerreotype of a couple that was taken in 1952,” he says. “They’ve still got that very wooden ‘we’re-sitting-for-a-long-exposure-and-we’re-not-happy-about-it’ expression, but they’ve got one hand over the other’s. They’re showing their intimacy… it conveys quite a lot.”

Then there’s what’s been dubbed “the creepy eye photo”. The “drawn-on eyes and eyebrows” on this portrait of the Thompson family from 1893 are an odd feature, Higgins says, likely added because somebody blinked or there was a problem with the exposure. “What’s interesting is this particular studio, Elite Photographers, I’ve seen them do a few others the same way,” he says. “I’m almost wondering whether it was something like a specialty or trademark they were known for.”

Touch-ups like this were more common than you might think, and understandable when you consider how much subjects would have paid to have their portraits taken, Higgins says. He thinks of it like an extremely early precursor to Photoshop: “You always could edit photographs, right from the very beginning.”

A Different Light is open to view at Auckland Museum until September, after which Wellingtonians and Dunedinites will get a chance to see if they can recognise a great-great-great-grandparent, or at least imagine what it was like to be knocking about in the 19th century.

And as you stare into the sometimes drawn-on eyes of the people in the photographs and put yourself in their shoes, just remember this: “They would say ‘prunes’, not ‘cheese’,” Higgins says. “Saying ‘cheese’ is a 20th century thing.”