As New Zealand remembers those lives lost in 20-century wars, New Zealand actor Michael Hurst reflects upon wars dating back millennia, and the role of storytelling in remembrance and resistance.

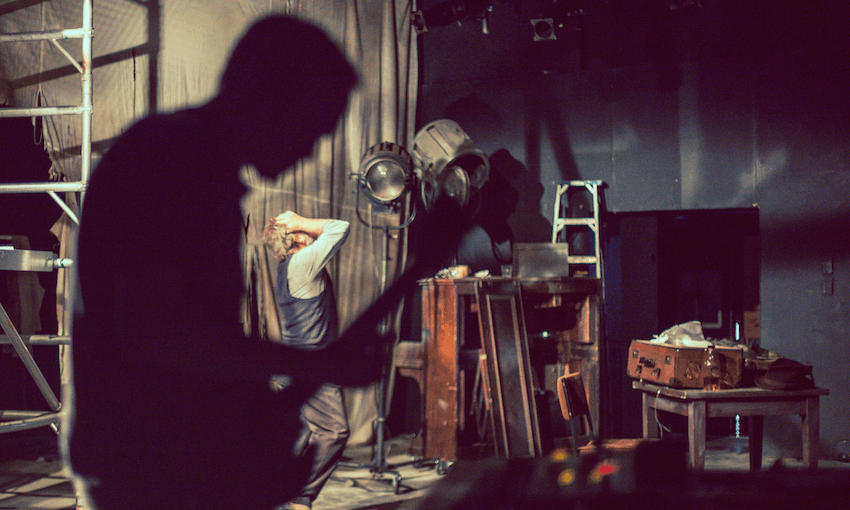

Tomorrow, I begin a five day-intensive rehearsal process for An Iliad by Lisa Petersen and Denis O’Hare. I performed it a year ago in Dunedin and I loved it. It was a profound experience to work at that level of storytelling, and with Shayne P Carter as the Muse, we were able to scale the walls every night.

The central character in An Iliad is The Poet. This guy is either about 3000 years old, doomed to wander the Earth telling the same story, or he’s just woken up in the alley around the back of the theatre and wandered in. Either way you will get his version of Homer’s seminal epic.

“It’s a good story. I remember a lot of it, I remember a lot of it.”

It’s the story of a world conflict, is what it is. For the Bronze Age Myceneans the Trojan War was a catastrophe. Hundreds of thousands of men emptied out of the Greek islands and were sent across the ocean to fight in a merciless conflict that lurched to-and-fro across a single strip of coastland for 10 years, “hurling down to the house of death so many sturdy souls, great fighters’ souls, making their bodies carrion, food for the dogs and birds.”

“What drove them to fight with such a fury? Well, the gods, of course. Pride, honour, jealousy, Aphrodite, some game or other, an apple, Helen being more beautiful than someone – it doesn’t matter. The point is Helen has been stolen and the Greeks have to get her back.

“It’s always something, isn’t it?”

And every time the Poet sings his song he hopes it will be the last time. Which of course it isn’t. There is always another time; there is always another war. Lest we forget.

The beauty of this play is that it is so immediate. It is as if the Poet is making it up as he goes along. Partly this is due to the wonderful translation by Robert Fagles of the sections from the Iliad itself, but more significantly it is the result of the Poet’s ability to slip in and out of the central narrative and comment upon what is being said. This is a really powerful device. For example, at one point, as Hector returns to the battle after visiting his wife Andromache, the Poet suddenly stops and asks the audience “has anybody seen what a front line looks like?”. He gets some photos out of his case, “from a different war but you get the picture”, and then describes a 20th-century battlefield, scarcely any different to those of the ancient world, littered with dead young men whose futures have been suddenly snuffed out.

“Ares is a democrat. There are no privileged people on a battlefield”, said the poet Archilochos around 640BCE, and he was right.

Homer had minstrels commit his works to memory so that we would all remember not just the brief, shining glory of war, but the awful cost; the cost to the women of Troy; the cost to the women of Greece; the cost to the people of the entire region. There was no recovery. The conflict saw two generations of men taken out of circulation and began a seismic shift in the demographics of the Aegean that would lead eventually to the death of a whole civilisation, the death of an older world.

Not surprisingly, given that I need to get the performance back into my brain, I find myself reflecting on the nature of memory.

Memory is the actor’s major tool. As long as “memory holds a seat in this distracted globe”, says Hamlet, clutching his skull as he hears the truth about his father’s murder, as long as he is capable of the act of remembering, he will remember not only the ghost’s appalling message, but also his own lines. Shakespeare’s theatre, itself a distracted Globe, was the very seat of memory, with many actors holding twenty or so plays in their heads at any one time.

Go back further. Committing the original Iliad to memory must have seemed like a miracle, right? How do you remember all those lines?

And with Homer we are dealing with deeper, more ancient memories that shift and dance on the limnal shores of myth, one foot on land, firm, the other lagging in the ocean. And the telling of these memories strikes us at the bedrock of the human condition, the loneliness of each and the need to recognise ourselves in others and to deal with life and inevitable death.

They shall not grow old as we grow old.

But the story grows inside you too, it becomes you. It’s a physical thing, a body memory. You burrow through it. And the story needs to be told. I think it is compelling. It compels me. And it needs to be told in this way because the one-to-one experience of memory takes us to the ritual place we all, at bottom, yearn for, staring into the fire, the prehistoric television. This is where the Story Teller functions as guide along the path to catharsis. This is where art is therapy.

Memory and remembrance. Lest we forget.

An Iliad is a great idea. It is epic and immediate and an enthralling script to climb through.

War is hell, but war is humanity’s black dog and we need to face it down and send it howling back into its cave.

An Iliad runs from Wednesday May 29 to Sunday June 9 at the Herald Theatre