Cricketer James Faulkner ‘came out’ on social media this week, except it all turned out to be a joke. Jack Cottrel responds.

It must have been a surreal experience. One dumb in-joke and the next morning, you’ve come out as gay.

Or not.

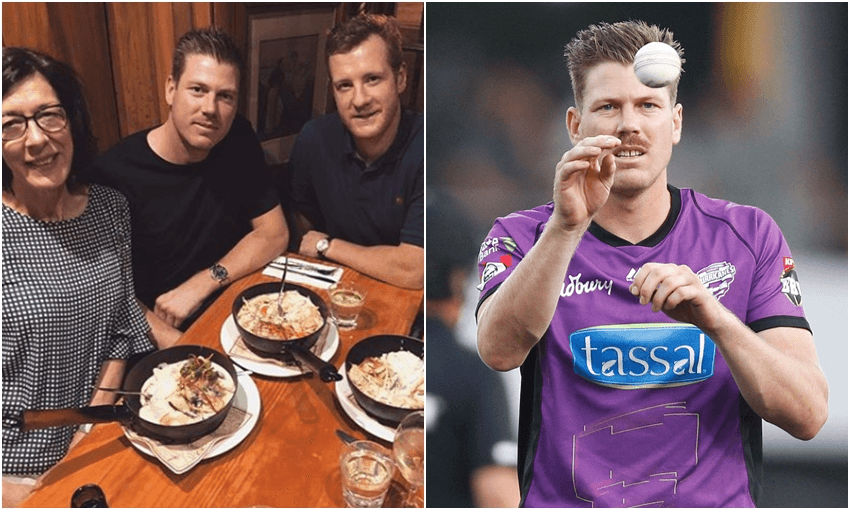

Australian cricketer James Faulkner yesterday trotted out what, in context, is some typically silly banter. Out celebrating his birthday with his mum and best mate who he’s flatted with for five years, he referred to his flatmate as ‘the boyfriend’, along with love-hearts and the hashtag #togetherfor5years. In context, for the people who know Faulkner well, it’s a standard ‘we’re practically married’ joke which isn’t actually that funny. In context, on a homophobia scale, it’s roughly 1.5 out of 10.

Unfortunately for Faulkner, he didn’t make the joke in a group chat. He did it on Instagram. Context went out the window and plenty of people (including media outlets) thought that Australian cricket had its first gay men’s player.

I’ll be honest, one of those people was me. Cricket is not exactly a popular sport among gay men. While I know literally thousands of gay rugby players, I only know about a handful of other gay men who even enjoy cricket, let alone play it. In the history of the sport, the only openly gay player is Steven Davies, who plays county cricket for Somerset.

Somehow, in the cyclical brouhaha of No Gay All Blacks, the fact there have been No Gay Black Caps either never features.

I’ve loved cricket forever, having worked in the sport to varying degrees and writing about it for years. Every queer person goes through moments when their sexuality or gender makes them feel entirely alone. For me, most of those moments arrive with the cricket season, whether it’s because other LGBTQ+ folks don’t get it, or because I’m the first out gay man someone has met in their entire cricketing career.

So I went to Faulkner’s post with a real sense of happiness. Someone had to be the first, so why not him? I was, of course, hit with serious homophobia in the comments. Not just the “practically married” foolishness, but the kind that calls me and people like me sick and depraved. Other people had been reporting the comments for hours, but the well for that kind of hatefulness is about as deep as the Mariana Trench.

And then, of course, the denouement. It was all a joke.

Faulkner’s follow up, thanking the LGBTQ+ community for the support he never actually needed, was kind of painful to read. His joke not only reminded me that I’m the only gay in the village (cricket team) but that it had provided a point for virulent homophobia to spring from. We’d been reading it so we could report it – reading it so he wouldn’t have to.

The idea that his ‘date’ post was never meant to be taken at face value was tone-deaf as hell, though not quite as tone deaf as the fans who came to his defence when actual gay actual people rightfully asked: “What the fuck?”

Faulkner didn’t apologise, rather he was misunderstood, and “good on everyone for being so supportive”. Perhaps we’d done such a good job of shielding him from homophobia that he actually thought none came through, even though it started up again pretty quickly.

Somehow, it seems we were supposed to have divined that Falkner didn’t actually mean ‘boyfriend’ in the way that usually accompanies hearts and hashtags, but in the way that… means ‘BFF and flatmate’.

And of course, it was roundly suggested that anyone who expressed genuine hurt over the situation was just looking for reasons to be offended. As though we hadn’t just waded through the swamp for at best, a bad joke and at worst, for someone who belittled gay relationships. No queer person needs to look for reasons to be offended. They come to us, with slurs aplenty.

In fact, I’m really not sure what Falkner thought the reaction to his initial post would be – good-natured boys-club ribbing? I want to believe no one could actually make a post like that without expecting some actual abuse, but the obliviousness of straight dudes will never cease to amaze me.

So, my ever-hopeful little gay heart got trampled on a bit, but it will survive. I do feel for the gay cricketers who are out there (though not actually out there) because they got to see a bit of what waits for them if they do decide to open the closet door.

I don’t think Faulkner should be castigated for this. But as he said, he got significant support from the LGBTQ+ community. It’d be good if he could actually pay that back sometime.