Alex Casey watches BossBabes, TVNZ OnDemand’s new reality series following Instagram entrepreneurs Iyia Liu and Edna Stewart.

Breaking news: eyeliner is over. Ever since eyelash extensions came onto the scene, Iyia Liu declares from her king size bed, eyeliner is just “not a thing” any more. It’s the first key learning of many from BossBabes, TVNZ OnDemand’s new reality series following Auckland influencers and e-commerce businesswomen Iyia Liu and Edna Stewart. Tell you what doesn’t seem to be over though – cupcakes. Iyia Liu can’t seem to get away from the bastards.

As someone who watched every moment of Iyia Liu’s gender reveal party on Instagram from my couch, and who once spent a whole day in a dark room at a business event with the woman herself, this show was made for me. Call it masochism, but I love pressing my greasy nose against the glass and watching rich people being rich. Remember The Ridges? The GC? The Real Housewives of Auckland? BossBabes is their younger, savvier, selfie-taking sister.

At 25, Iyia Liu has made several big waves over her relatively short career. She famously paid Kylie Jenner $300,000 to wear one of her first products, a suffocating Edwardian corset waist trainer and quickly became an e-commerce millionaire. But it was in 2018 that she became infamous, her insta-bait dessert box company Celebration Box accused of false advertising, missing orders and blocking people who complained on social media.

In July, the Commerce Commission found that Celebration Box may have breached the Fair Trading Act in several instances, but no further legal action was to be taken against them. Later, at her mansion party, she refers to whole fiasco as “a little hate”. On with the show, then!

Her lesser-known costar Edna Swart, 29, is the founder of Ed&I swimwear and body range. In episode two, we get a welcome look into her fascinating backstory. Edna was born in South Africa and adopted at birth, moving to New Zealand at the age of five. Sitting on her car bonnet at sunrise in Takapuna, she Facetimes her biological mother back home, where the sun has just set. It’s a still, poignant moment in a haze of shopping trips and photoshoots.

Because it shouldn’t really be a surprise that BossBabes is extremely pacy, with fleeting scenes of glamour and excess perfectly mimicking the relentless Instagram scroll through glossy lives you will never live. In episode one, Iyia is throwing a party in her brand new house, which looks a hell of a lot like the sprawling Gatsby-esque mansion they filmed House of Drag in. I once had toxic mould mushrooms growing through my ceiling, which is basically the same thing.

Having a lavish party is a way to “get people talking about you and tagging you in” says Iyia, who has shelled out for balloon garlands, samba dancers and light displays, all because they will “look cool in the stories”. The brazen way these women talk about Instagram is, frankly, breathtaking. However detached you may pretend to be, everyone on social media is constantly making choices to brand themselves a certain way – at least this lot are upfront about it.

The day after the party, they review their Instagram reach over espresso martinis at the Viaduct. “This one got really good engagement,” Iyia notes.

A surprising element to BossBabes is that both women turn out to be stone cold weirdos, which makes the show a hell of lot more interesting to watch. While setting up an absurdly large white chocolate cake for the party, Iyia and Edna are forced to consider the location of the sun in relation to the rapidly-melting icing. “Never eat soggy Weetbix” muses Edna, staring at the horizon with a furrowed brow. “It’s not going to move,” says Iyia, “the sun stays in the sky.”

I gotta tell you, I really wasn’t expecting Boss Babes to be funny. Complete with golf carts, bottles of Veuve and guests arriving by chopper, the cost of Iyia’s house party comes to a cool $20,000. It’s worth it, they conclude, if it means that they can find her a boyfriend. “The ROI [return on investment] is massive,” Edna tells the camera, deadpan. “You can’t put a price on that.” I chuckle to stop the tears, throwing my latest credit card bill straight in the bin.

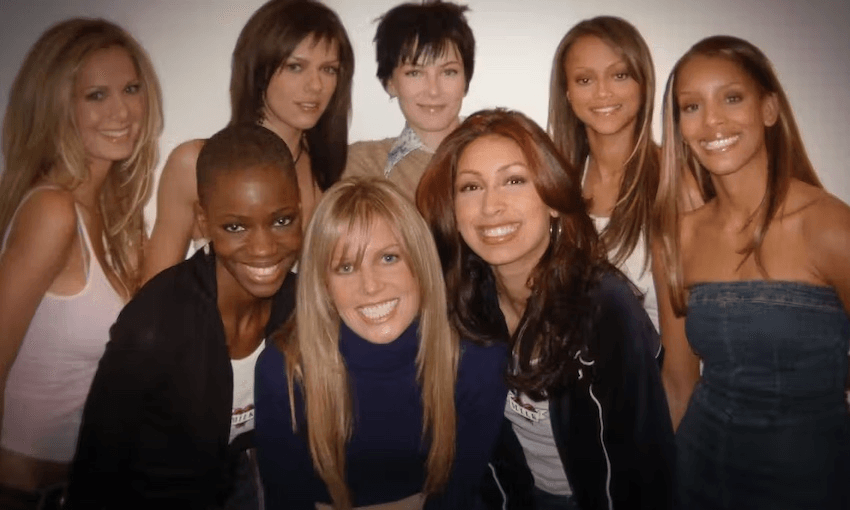

The investment in the party pays dividends. Iyia’s invited Max Key without telling ex-girlfriend Amelia Finlayson, who feigns anger at the news. “I actually hate you,” she smiles, flicking her hair. Elsewhere, Max skulks in the corner behind some Heartbreak Island boys. Seeing our shonky Marvel universe of yung Spy celebs is a real treat and, in many ways, Iyia’s party is our Endgame. Because Max has pulled Amelia for a chat, and he’s giving her ‘the eyes’.

While Boss Babes provides classic reality TV low stakes melodrama, there’s also some – ahem – meatier issues tackled. Frank discussion around cosmetic enhancements are injected throughout the show. Edna tells the camera she started Botox at 25 and has spent around $20k on her face and body since. In episode two, Iyia is preparing for her Brazilian Butt Lift, a gruesome procedure that will have her walking out of surgery with notably larger buttocks.

“I love slapping butts,” notes Iyia, “I slap three to five butts per week on average… It’s not so much about having a massive butt, its more hip to waist ratio.” The pair’s philosophy is that loads of people are getting this work done, but nobody is talking about it. That might be true, but I still couldn’t help but see the chain of influence before my own, crinkled, terrible eyes. If Iyia’s goal is to look like Kylie Jenner, then how many young New Zealand women now want to look like Iyia Liu?

Watching BossBabes, I thought of the teenage girls I interviewed who told me about the ideal body shape – big bum, big boobs, a tiny waist. At 16, they are already considering their cosmetic enhancement options thanks entirely to influencer culture. I’d really love to see the Boss Babes interrogate their own place in that culture, because the most raw reflection the show has provided so far is me, standing in front of the mirror after two episodes, staring woefully at my own flat arse.

BossBabes is streaming now on TVNZ OnDemand.