The new Neon docuseries clears away the clutter from this messy saga and refocuses on the person it was always really about, writes Sam Brooks.

The question of how to engage with art made by problematic people is one that’s never really been resolved. If you cancel the artist, do you cancel the art? How do you resolve your relationship with art that’s so important to you, knowing that the person who made it has done so many gross things? Personally, I believe that you should engage with whatever art you want, but for the love of god, don’t publicly self-flagellate over it. Keep it between you and your own conscience. If it makes you feel bad, interrogate that. If it doesn’t bother you, all power to you. The world keeps turning forward.

A while back, I rewatched Woody Allen’s tremendous Hannah and Her Sisters, featuring a Dianne Wiest performance that remains one of the best to ever win an Academy Award. It’s a film which holds a thorny place in my heart. At the time of my rewatch, it was decades after Dylan Farrow made her first sexual assault allegation against Allen, her adoptive stepfather, after which she had been dragged through and then sceptically interrogated by the media. It was also only a few years since those allegations had reared their head again, around the time Cate Blanchett was winning a mantlepiece’s worth of awards for her performance in Allen’s Blue Jasmine. Still, despite all this uncomfortable knowledge, I watched Allen’s 1986 masterpiece with joy.

After Allen v Farrow, I can definitively say that I will never watch Hannah and Her Sisters again.

Allen v Farrow is directed by Kirby Dick and Amy Ziering, the duo behind documentaries The Invisible War and The Hunting Ground, and it has the same unfussy, straightforward approach as their earlier work. They clearly have two goals here. The first is to provide an outlet for Dylan Farrow to finally tell the full story of what she claims Allen did to her: namely that he sexually assaulted her when she was seven years old in 1992. Allen has consistently denied these allegations, and each episode of Allen v Farrow ends with a line of text reasserting that.

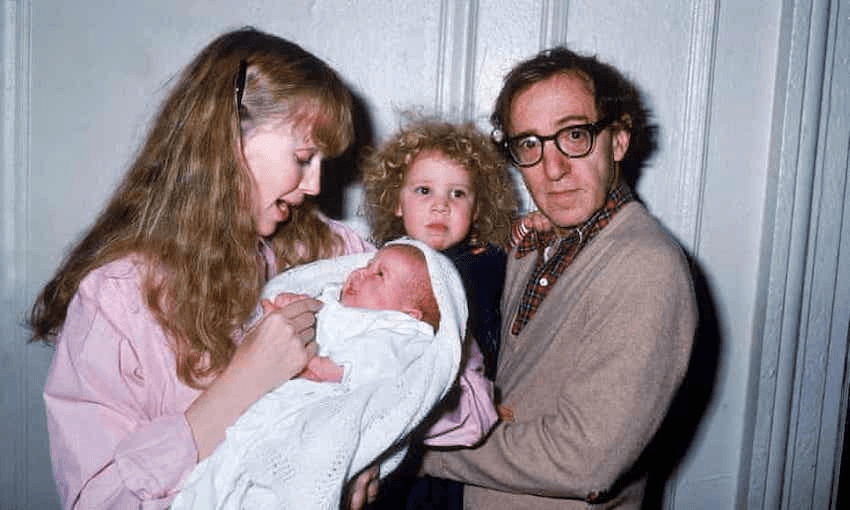

The series’ second aim is to produce a definitive document of the mess around these allegations, which played out very publicly in the media in the 90s – alongside a vicious custody battle which painted Mia Farrow, Dylan’s mother, as a vengeful woman scorned – and resurfaced again when Dylan’s open letter detailing the alleged abuse was published in the New York Times in 2014. It’s a convoluted saga that also involves Allen’s affair with Mia Farrow’s adopted daughter, Soon-Yi Previn, while he was in a relationship with Mia; the cultural shift from disbelieving women by default to actually listening to their stories; and an entire artform’s relationship with one of its most heralded auteurs.

I’ll be frank, Allen v Farrow is a deeply unpleasant watch. When you turn it on, you’re committing to hearing multiple accounts of how Dylan Farrow’s very private trauma became a public battleground. You’re committing to hearing about the legal mess that happened in the wake of it, including a wealth of unheard details around the custody case. You’re committing to watching a seven year old child discuss her abuse. It’s not an easy watch, and if you already know where you stand on this case I understand not wanting to spend your time reexamining that. It’s not just the initial trauma that’s exhausting here, it’s the 20 years of bruising fallout.

Importantly, the series contextualises the entire case within the culture of the time. When the allegations were first made public, Allen was in the middle of his ’90s renaissance, protected by his status as a commercially successful and critically beloved filmmaker. The culture at large did not want to believe Dylan Farrow, and neither did the press. A few years after she wrote her open letter came the Harvey Weinstein reckoning – prompted in large part by a New Yorker investigation into Weinstein by her own brother, Ronan – and the dawn of the #MeToo era. Suddenly, people were more willing to believe her. “Timing” is a bleak answer to the question “Why didn’t people believe Dylan Farrow?”, but a crucial one.

The series also never forgets that engaging with this case means questioning Allen’s considerable legacy. Although he doesn’t appear in the series, for fairly obvious reasons, he’s present throughout via archival footage and clips from his films. Believing Dylan Farrow means not believing Woody Allen, and if you’re on Farrow’s side then hearing Allen consistently deny her allegations over two decades will make you furious. Most jarring are excerpts from Woody Allen’s 2020 autobiography, Apropos of Nothing, read by the man himself. Hearing his distinctive voice in this context does a lot to help the audience disengage from his art. This isn’t Allen the actor, or Allen the director. It’s Allen the man, in the present day, denying these allegations as he has done all along. (He has released a statement denouncing the documentary.)

The most valuable thing about Allen v Farrow is not necessarily the investigation into the allegations. If you’ve always believed Dylan Farrow, as – for clarity’s sake – I do, you will continue to do so. If you’re still a steadfast supporter of Woody Allen, you’re unlikely to even engage with this series. Instead, its principal value is in the way it reframes the story as one girl’s truth.

At one point in the series, Dylan Farrow looks back on the videotape, recorded by Mia in 1992 and later used in court, in which she first talks about Allen’s alleged abuse:

“What’s in that tape feels like that is who I am when you strip away everything else. You look underneath all my layers, down to the very centre of who I am. I am that little girl in the tape.”

At the end of it, Allen v Farrow isn’t about a great American filmmaker, or a drawn out, messy battle between two estranged adults. It’s about a girl, her trauma, and her need to own the story around it. For decades, Dylan Farrow’s pain has been exacerbated by the lens constantly being pulled away from her. This series places the focus back where it always should have been. Who the fuck cares about the art?

Episode 1 of Allen v Farrow is streaming on Neon now, and is available on Sky Go.