Like the road safety campaigns around Christmas and Easter, Matariki is a time to be extra vigilant. Look after your whānau, tune into the ones who hide their faces, and observe the tohu, both seen and unseen.

This post contains discussion of suicide: please take care.

The curator of the Hit Home project, and Joy’s actual aunty, Meritian Sekene, tried several times to pry her niece away, worried that the attention might be suffocating. But in a room where grief and loss reverberate with absence, who could ask for anything more than Joy?

Just over a year ago I entered through the same front door and Joy was nowhere to be seen. I was in Rotorua, at a healing wānanga for whānau bereaved by suicide. The Hit Home art exhibition had travelled all the way from Manurewa and set up in the wharekai at Tunohopu Marae. My brother had been gone for just over six months.

The front door, where the exhibition begins, looks like any other front door: innocuous in white with bevelled edges and a brass handle. But appearances aren’t always deceiving, especially to those of us living with hindsight.

Bethel Fualau created Hidden Layers after her partner took his life in 2019. Left behind to care for their one-year-old daughter alone, she turned to metaphor: “The front door looks almost perfect on the outside. It portrays how the world views me: you’re so strong. I don’t know how you do it, etc. But once you take a step into my life, you see all the underlying issues that no-one else sees.”

Bethel told me that she finds it hard to watch people approach the door. Some just stand there, like I did, looking and gulping. It may as well be a mirror. Once you cross that threshold you can never go back.

In an environment where mental health campaigns constantly urge people to “talk about it”, an art exhibition about suicide by those bereaved amounts to more conversation than most people can probably handle. Or want to.

But those of us dealing with the aftermath of suicide don’t have a choice. These are the walls we live in now.

Artist Graham Jackson’s metaphor is the actor’s masque, and his walls burst with colour and rage. The masque beams brightly but the eyes say Help Me.

“The message for males is always to reach out and ask for help,” says Graham in his accompanying text. “But jack that, it’s easier to say than to do. Sometimes you can’t even ask for help from those closest to you.”

The words sting because they’re true and I am living with regret, but Joy was singing Tutira mai ngā iwi from the stage and she was waving for me to join her.

After seeing the Hit Home exhibition, the obvious occurred to me: anyone can do art. Not because they are necessarily “naturally” talented, not because they have delusions of fame, but because they have something to say that is beyond the reach of words. Art is therapy. Creating is a very real and practical antidote to death. Nothing is wasted, not even regret. Art describes what words are insufficient to explain. Not only that, one story can have a thousand interpretations.

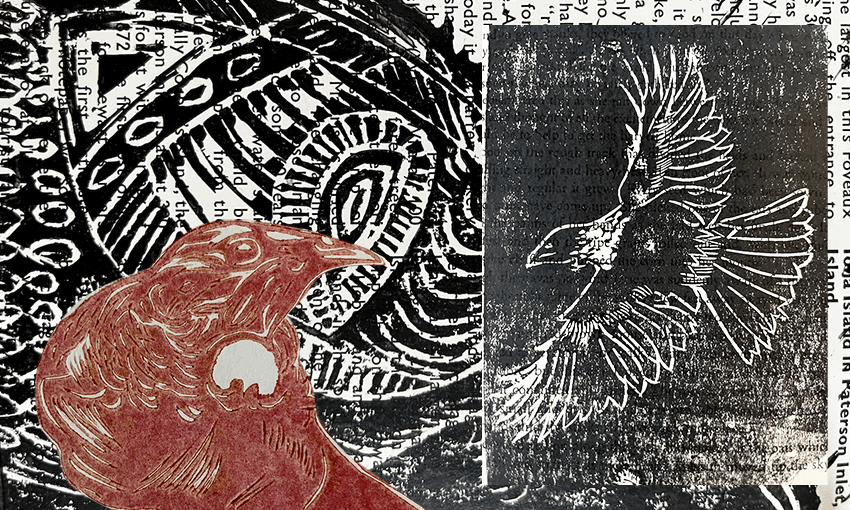

Seeing my own work on the walls of the second Hit Home exhibition, now almost two years after my brother’s death, was wild. Meritian invited me to share my work alongside the original artists and their new works, after I told her that the Hit Home exhibition had inspired me to enrol in art classes at home in Wellington.

I started with an A5 sheet of lino and a single red-handled Speedball blade I bought from Pete’s Emporium. I used up a whole tube of black ink in a month. I didn’t realise how different a tūī was to a duck, different to a penguin, different to a hawk, until I tried to carve one. I was pretty bad. You know, objectively bad.

But I learned quickly that the problem was less to do with natural skill, and more to do with the fact that I just wasn’t looking. I wasn’t paying attention to detail. Always moving too fast.

After lino, I quickly progressed to other techniques: cyanotype, monotype, drypoint. Anything involving colour. I was especially drawn to magenta. Suicide is an inferno. The earth is scorched: two parts red, one part green.

One day, I found a black gull’s feather in the middle of my path. I picked it up and took it to art class and printed it over and over again. Each time it went through the press it absorbed and returned different colours. I was so hopeful, filled with expectation as I inked the plate and spun the wheel, but it was the shadow prints – the ones on the scraps of paper used to protect the press – that came out the best. They captured the kind of detail the eyes have to be practised to see.

In this way, I learned that sometimes, the things we mean to throw away are the things we end up framing. I also learned that sometimes upside down is the right way up. And sometimes, you cannot see what’s in front of you until you take something away. Reduction as method. Without grief, how would we know joy?

That art can be therapeutic is hardly a new idea. But it wasn’t until I tried it myself that I understood why the kupu “toi” in Maori – which is often narrowly translated in English as “art” – also means “pinnacle” or “summit.” Toi refers to the place where seeing becomes knowledge and wisdom.

If only these lessons had come sooner. “If only…” is the chorus of the bereaved.

If only I had known that there are certain times of the month and year, certain phases of the moon, when people can be especially vulnerable, I might have been better equipped to see the tohu that were hidden plain sight. Too many of us can see only in retrospect.

Matariki, when the days are short and dark and very cold, is especially a time to take care and be more intentional in our relationships.

This is at odds with the Gregorian calendar, which is right now demanding more and more of us, piling up deadlines and pressures, keeping us at work long after the sun has retired.

The physical environment of these southern skies is guiding us to slow down and stay home, to shed the unnecessary weight and draw close to the ones we love. But the pressures of the social, economic and political worlds, imported from the northern skies, are dragging us in the opposite direction. In some cases, these pressures are associated with Matariki itself, with festivals and events and obligations to show up and perform looming large in the weeks ahead.

When te kāhui whetū returns, there will be celebrations, waiata, remembrance, hākari, and even a public holiday. But that is several weeks away. The setting of Matariki is no less important than the rising.

If I think back to this time two years ago, it was now – when Matariki had retreated from the sky – that my brother began to pine and fret. He was weighed down with things I couldn’t see – or was moving too fast to notice. He was withdrawing; leaving without saying goodbye, spending his days in darkness, alone, without company. We found out later that he went to the doctor who prescribed antidepressants and sleeping pills, but medication alone did not cure the loneliness or fear or fatigue or paranoia that had taken grip of him. It wasn’t long after that till our tūpuna came to take him home.

This knowledge weighs heavy, but like all the artists involved in the Hit Home project, we share what we’ve learned in the aftermath of suicide not just for our own healing, but so that others will never have to cross this threshold and live within these walls.

This is the message that hits home. It is a message of prevention. Like the road safety campaigns around Christmas and Easter, Matariki is a time to be extra vigilant. Look after your whānau, tune into the ones who hide their faces, and observe the tohu, both seen and unseen.

Art can be the medium for the transfer of this knowledge. It carries wisdom, sadness – and of course, Joy.

In the end, I never got to say goodbye to her. She was dancing ‘Gangnam Style’ with all her cousins on the stage when I had to leave for the airport. Before I left, I stood at the front door and took one last look at her; the beaming smile, skinny limbs and fluoro socks kicking high to the sky. Meritian told me that Joy survived open heart surgery at the age of three months.

“She’s a real fighter, is our Joy,” she said.

The Hit Home Project will be on display this weekend at 9/3 Brick Street, Henderson, Auckland (Saturday June 4, 10am-6pm and Sunday June 5, 9am-3pm).

This is Public Interest Journalism funded through NZ On Air.

Where to get help

Need to talk?

Free call or text 1737 any time for support from a trained counsellor.

Lifeline

0800 543 354 (0800 LIFELINE)

Youthline

0800 376 633, free text 234 or email talk@youthline.co.nz or online chat

Samaritans

0800 726 666

Suicide Crisis Helpline – 0508 828 865 (0508 TAUTOKO)

Depression Helpline – 0800 111 757 or free text 4202 (to talk to a trained counsellor about how you are feeling or to ask any questions)

depression.org.nz – includes The Journal online help service