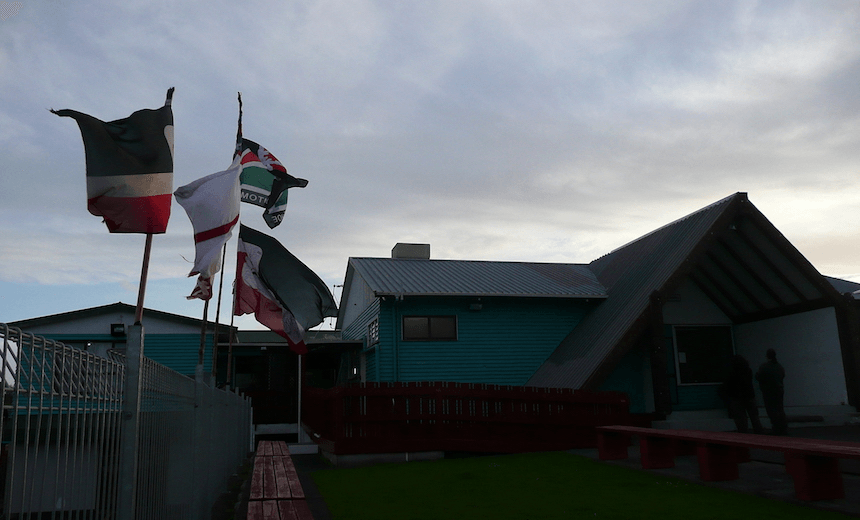

On the 10th anniversary of the Tūhoe raids, we look back at a book published by Rebel Press in 2010 recounting the experiences of 16 people effected by Operation 8.

On October 15 2007 the ‘war on terrorism’ arrived in New Zealand when more than 300 police carried out dawn raids on approximately 60 houses all over the country. They used warrants issued for the first time ever under the 2002 Terrorism Suppression Act (TSA). Police claimed that the raids were in response to ‘concrete terrorist threats’ from indigenous activists. The people targeted were overwhelmingly Māori. On that day, police arrested 17 people: indigenous, anarchist, environmental and anti-war activists. Police took into custody people from Tūhoe, Te Atiawa, Maniapoto and Ngā Puhi along with a few Pākehā.

Rangi Kemara remembers the day the raids came to his house in Manurewa.

Go back to Sunday, 14 October 2007: the night before the raids. I had been in bed all day. I had hurt my back the day before, so I spent the whole day lying down. I was watching these undercover cars going past, wondering what the hell was going on out there. The day before our neighbours had been in a huge fight, and they had wrecked their place, so I assumed that the cops were looking at them. I was inside my caravan, parked just in front of Tuhoe Lambert’s house in Manurewa.

About 4.30 in the morning, I woke up to a couple of cars sitting outside; again, I assumed it was the neighbours because of the events that had taken place. Tuhoe and his wife Aida were awake. They always woke up at about 4.30 in the morning and had a cup of tea. I went back inside the caravan and lay down. More and more cars were arriving outside and parking down the street.

Where the caravan was situated, it was like a sound shell; I could hear everything. There was an enormous noise and a whole lot of shouting. I could hear the cops yelling at the neighbours. I thought they were raiding them; it seemed like a full-on bloody raid. But as their voices became clearer, I could hear that they were actually telling the neighbours to get back in the house. It took a minute or two before I suddenly realised: No, they are actually raiding me – raiding us. I stepped outside the caravan. In my initial shock, it seemed that the sky had been lit up with stars. It was, in fact, the police lights on the front of their guns that lit up the place; it was almost like standing in a glowworm cave.

Almost every corner of the property had guys with guns hanging over the fence. The cops were on the megaphone yelling for me to come out. As I was about to step out from behind the caravan there were armed officers on either side, right around in a semi-circle. The ones that were on my left were yelling that I had a gun in my hand, which was crap. It was one of those situations that either I stepped out and got nailed, or they would come around the corner and nail me. So I had this little thought to yell out that I had no gun. I thought that would ruin their day, and make things more difficult. I said about three or four times that there was no gun. ‘No gun. No gun. No gun,’ I said and then stepped out from behind the caravan.

At this point I was escorted out by armed men. They were not your average armed offenders. You see the AOS on TV all the time. These people were another level up. They were an elite squad brought in for this particular raid. They did the first part of the raid. They brought me out and lined me up against the fence outside. Then about five minutes later everyone who was in the house was brought out. There were quite a few people staying at the house because there had been a family gathering the night before. We ended up lining up right down the block, about half the street. We were placed down against the fence, handcuffed and forced to kneel down on the pavement. There was an armed officer standing behind each one of us with a rifle to our head.

Tuhoe’s partner, Aida, became very agitated because the younger people had firearms to the backs of their heads. She began to voice her opinion about that quite strongly. The police reaction of course was to try and shut everyone up, but they were unable to silence that kuia. It was obviously a distressing thing for everyone involved, but much more distressing to see children put through that process.

We were handcuffed with those little plastic cuffs. Then it started to rain quite hard. It was pouring down. Not only were we kneeling there against the fence with all the neighbours watching and dozens and dozens of very hyped-up crazy police behind us yelling and screaming, but it started pissing down rain. I was thinking, Gee, I wish I had put on a raincoat before coming out.

The cops then tried their separation techniques. They put us in different areas to try to coerce a quick confession or to achieve whatever they were trying do. I had seen this type of thing in the past. It had happened to other people. I had also been through something similar to this once before and had seen the type of destruction these cops can do. They are so amped up; they will go to any length to achieve what they want.

They were looking for firearms. They wanted to search the car. I could have sat back and said, ‘Stuff you, you’re not going to get anything from me,’ but they would just break everything—break the caravan, break the house, break the car. So when I was trying to explain where my car keys were, I said, ‘They are right there by my firearms licence.’ That is when the next big dialogue took place. One of the officers was quite adamant that there was no way I had a firearms licence.

It occurred to me then that they had obviously mis-instructed these guys in order to get them so heightened and amped up, and oddly enough, almost shaking in their boots. It was kind of strange for me; really it should have been the other way around, and for part of the time, it was. I noticed the dissipation of their anxiety the moment that they realised that they had been misinformed. It was almost like letting the air out of a balloon. It was like night and day between two different events and the attitudes of the officers.

After that, they were exchanged out; the commando cops were pulled out and replaced with the ‘normal’ armed offenders squad. The second team of about 15 to 20 cops came in, and they were wearing the ‘normal’ armed offenders black garb. They maintained the scene until the detectives who had obviously ordered the whole thing turned up. Once they took over, the armed offenders were pulled out, and a whole lot of armed police in blue uniforms turned up. So there were three entirely different sets of police at the place.

At that point, I didn’t realise that a whole lot more people had been arrested. I thought someone must have complained to the cops because they saw one of my hunting rifles being loaded into or unloaded from my car. I hadn’t worked out exactly what was the purpose behind this entire masquerade, until I was questioned by one of the detectives, Hamish McDonald.

He said, ‘We are going to charge you with unlawful possession of firearms.’

And I said something along the lines of, ‘Unlawful possession? How is it possible that I can unlawfully possess firearms that I lawfully bought?’

The thought hadn’t really crossed my mind at the time that such a thing was possible, but apparently it was. That of course was all within the thinking that maybe someone must have complained.

Then McDonald said, ‘We also want to question you about terrorism.’

Then I thought, Whoa. Hang on. That’s not a neighbour complaining about a firearm being loaded into the car out of my gun vault. We are talking about the silly stuff now. It was then that I had to resign myself to the fact that this was going to be a long one; it was not going to be an in’n’out today event. They had gone beyond the issue of whether something was criminal or not, they had stepped into the political realm of silly irrationality and illogical absolutism.

So they trucked Tuhoe and I off down to the Wiri station first, and we sat in the cells there for a few hours. Then they brought us over to the Auckland central police station for another few hours. This was my first time in the cells, locked up in a police station. My main concern was for Uncle Tuhoe, making sure that he was all right. Obviously, the cops didn’t really give a shit about his health, and it wasn’t until a week later that the medicines he requires to keep him alive and kicking were afforded to him.

We eventually ended up in the cells where they hold prisoners before being arraigned in court. Only on seeing others who had been arrested that day, did I realise that this entire charade was linked into a much bigger police raid against activists from all genres.

As it unfolded, I began to see how enormous it was, just how far and how deep this craziness had gone.

We were in the last slot of the day at court; it was close to 5 o’clock on the 15th of October. They just read out the charges against us. I was listening to see where this terrorism charge had gone, but at that point we were just charged with unlawful possession of firearms. I didn’t really get how the whole terrorism accusation was being played out. I thought that if you are not charged with something, how the hell could they hold you?

We ended up being detained, ‘held on remand’ as they call it, on firearms charges. Normally, these are not charges for which people would be held in custody. We were taken back to Mount Eden prison, ACRP (Auckland Central Remand Prison), and put into individual cells, what some would call solitary confinement, for a day or two until they found places for us in one of the standard wings.

The wing we were held in was strange. It isn’t the place they put your average person. It is a mixture of people being held on behalf of Immigration – I think Ahmed Zaoui was in that wing at one time – and there was an Iranian guy previous to us who had been held there because he refused to return to Iran. It is kind of a quasi-political wing that I never even really knew existed. We stayed there awaiting the decision of the solicitor general as to whether or not the terrorism charges were going to be laid.

The next thing we tried to do was to notify our families that we were locked up. The prison authorities somewhere further up the chain were not allowing us to use the phones. That went on for two or three weeks. We were almost in the last week when we were finally able to get phone calls out, and I notified my family that I was being held in prison under the Terrorism Suppression Act (TSA).

Later, we found out that they had been waiting for a police monitoring system to be installed in the phone system before we were allowed to make calls.

Read the rest of Rangi’s story and more in The Day The Raids Came from Rebel Press.