The 1954 novel The Lord of the Flies by William Golding, a story about young boys shipwrecked on a desolate island, is a parable for the supposedly innate cruelty and selfishness of human nature. This week, an excerpt was published on The Guardian from the book Humankind by Dutch historian Rutger Bregman, who claimed to have discovered the “real Lord of the Flies”. The story of six Tongan teenagers who were shipwrecked for 15 months, and the man who rescued them, has been shared far and wide as proof that in the same situation, young boys might in fact be kind and collaborative instead. The problem is, writes Meleika Gesa, this retelling erased the voices of the boys themselves and the Tongan values and knowledge systems that prepared them for survival.

I’m often reminded that I am not the preferred narrator of my own story. That my life and struggles would look more believable and trustworthy (code words for marketable and consumable) if they were told from mouths that do not belong to me, my family, or my people. The coloniser wants to own you and your experiences and exploit you however they wish. There are so many instances in life where I’ve seen this firsthand.

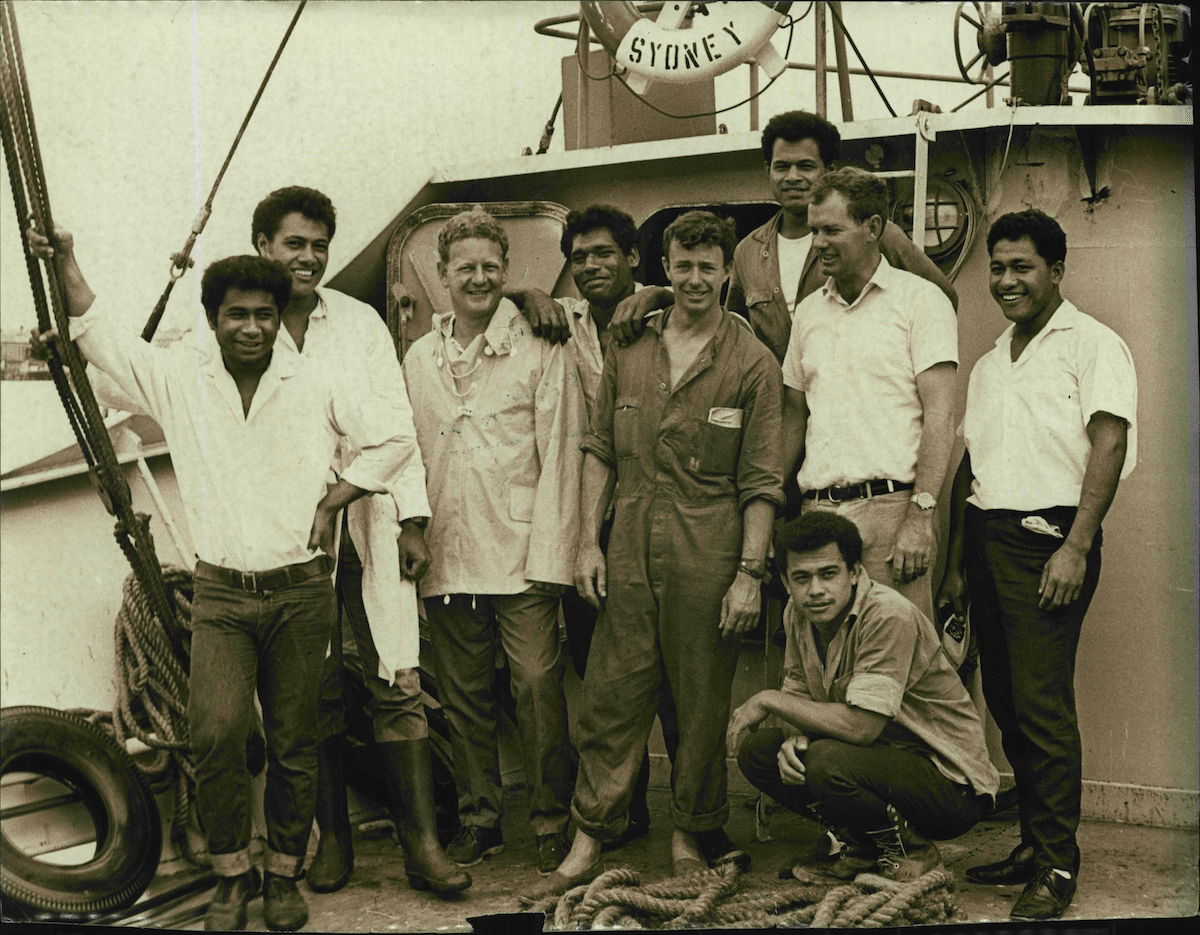

The most recent is when I stumbled across the story of the real Lord of the Flies on The Guardian, which uses the resilient story of six Tongan boys, now men – Tevita (David) Siola’a, Sione Fataua, Luke Veikoso, Fatai (Stephen) Latu, Kolo Fekitoa and Sione Totau (now known as Mano) – who survived being stranded on the island of ‘Ata for 15 months. It took me a while to read because it never really shares the story of the boys. It focuses on the white man who rescued them, as interpreted by the white man who “discovered” their story, who compares their journey to a book by a white author. As a reader, we’re left in the dark about these resilient young men and the cultural values that helped them survive.

This story (or what it missed) resonated with me because they are Tongan, like me. I’m from Fahefa, Tonga, specifically. I’m also a proud Torres Strait Islander, from Mer (Murray) Island, from the village Bauz, from the Zagareb, Dauareb, Magaram, Komet tribes, to name a few. I grew up on my homeland, Mer Island, in the Torres Strait. I went to school there, walked up the one dirt road and waved good morning to anyone watching from their veranda. I was taught the winds of Mer and how to hold a line and when the fish tried to bite, it’d tug or vibrate. My father would take me diving and I would always try to swim to the bottom. I would never reach it, but the ocean always made me feel grounded. My father reminisces about how surprisingly quick I picked up diving at such a young age. My old people like to say it’s in the blood. I think we’re born this way.

I have had family go missing by sea; my father went missing himself. A small frigate bird was with him the whole time. In my child’s memory of the story the bird saves his life. My mother says it was probably because I was so small, four or five years old, I just thought Rescue (the name we gave the bird) saved him. My father told me that the engine of the boat, ironically named Rock Steady, stopped working. He managed to anchor the boat on one of the reefs, but wave upon wave smashed into their boat. They were sinking. He and my three awas were left sharing one small can of soda. When it got dark, waves still soaking their bodies, my father tells me he tried to upset the gods, just like Māui did, by throwing his cargo away, their catch, before he fell asleep. He hoped this would help, because Māui always upset the gods and somehow, this benefited the people. He awakened to the boat being pulled by a strong current, and the tide going down. Soon after, my father and awas were rescued by a teacher who went out to look for them. His great comfort was the baby frigate bird, who he planned on bringing home. Another family member, big awa, John Tabo, went missing for over 20 days with his son and nephew, John Jr Tabo and Tom Tabo in 2006. They survived by eating squid, shellfish and drinking rainwater. They kept their phones off as much as possible to conserve battery until they finally had signal to text for help. Both times, their knowledge of the sea was used to survive. Both stories represent my cultural backgrounds. Most importantly, both stories were told by the men themselves.

The story of the six Tongan boys stranded on ‘Ata was told to me at a young age. The story I was told is different to what the author shared; it also didn’t focus on the rescuer. I knew six boys left home and then found themselves stranded on an island and lived off the land to survive. I’ve been told many stories about both my peoples getting lost by sea. But I remember this one because the boys were stuck on ‘Ata, the “Rock Island”. I also remember that it was the same island where my people were kidnapped and sold as slaves. Colonisation, slavery and racism is tightly woven into the boys’ story, yet the article I read gave it no more weight than if it were a footnote, or they had been taken on an adventure: “…a slave ship appeared on the horizon and sailed off with the natives.”

The remnants of “blackbirding”, which affected many islands of Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa, aided these boys. What was left behind of the lives of the people who were stolen is what helped keep the boys alive. As a Tongan, this part is heartbreaking.

Cultural knowledge was absent from the article that went viral. The fact they were Tongan wasn’t emphasised in the sense that it wasn’t acknowledged that it held importance to the story or their survival. How can you be surprised that Pasifika people, specifically Tongan, can survive on an island?

Their story was used to uplift another – the captain who rescued them. How do you write a story about Tongan boys who survived being stranded on an island and at the same time barely mention them? Their story is told through a colonial lens, the familiar trope of the ‘noble savage’. The author quotes another article that refers to Mano, at aged 67, as a “child of nature”. Even as adults, their wisdom, courage and resilience is seen as childlike through a white lens.

I belong to the Tongan diaspora. I live in Australia. I grew up differently to how my father grew up, who was raised differently to how my grandmother was raised. It’s inevitable in any diaspora; your experiences and how you exist within the world around you will be different to those before you. But our values and expectations of how we exist is the same. Tongans are taught to share from the beginning and to treat everyone like family. You’re taught to survive together, not “every man for himself”. It’s hard to exist without community. We’re humble by nature and hold a lot of respect for our elders and women, especially the matriarchs of our families. We’re generous and empathetic people, who are somehow always smiling. Always flaunting our Nifo Koula, if we have one. All of this tied to, what I later in life learned is called, Anga Fakatonga, the Tongan way.

When I read the article, this is what had been erased. Just look at Fetai, when he had broken his leg from trying to seek help. The boys set it back into place, teasing him as they aided him. There aren’t any details on how they knew this, why they chose the materials nor what it may have looked like. When I was younger, I remember my father would always say there is a Tongan way of healing your body, that’ll make you stronger. The old sea captain attributes their survival to “handiwork, an old knife blade and much determination”, but it’s also testament to our value system; these boys worked together to aid their friend, their toko, and used customary knowledge to heal Fetai’s leg. These boys created a community, a small family and worked together, as they were taught. They survived because of the value system we have and the knowledge we pass on to our children. This is true for every Pasifika nation.

Just look at how we’re surviving Covid-19 together. My family have given away food to our neighbours and checked up on friends and family because that’s how we survive. I know many Pasifika people who’ve done the same. Look at Māori in Aotearoa and Tokelau enacting inati, a system of sharing and equal distribution of essentials and fish. Back home in the Torres Strait, we get told the story of the fisherman who went out with nine friends. The fisherman then caught nine fish. He went home with no fish. It’s ingrained in us to give to others first. Pasifika people survive together because it is in our lore and values to exist together – that is how these boys survived.

The original article could’ve done more for the six men. The story should have been told by a Tongan. The story should have been told by the men themselves and their families. This is their story, will always be their story. The article doesn’t mention how the boys felt or why they made the choices they made. It lacked their perspective. It lacked the very Tongans the story was about, with the exception of Mano. But even then, Mano was sidelined. He deserves to share his story how he would want to.

It worries me that there is interest in this story from film-makers, from all around the world. Who will benefit from it? Will the man who rescued them, Peter Warner, continue owning the rights? Will these men benefit from this project? Do they all even know how much their story has impacted people? Who will tell this story? I hope that this story is directed by a Tongan and the dialogue is in Tongan. I also hope that these men gain the rights to their own story. Warner still owns the film rights to the story, which to me is bizarre because of the very fact that it isn’t his story to tell, nor own. But whiteness allows you to think you can own anything. Just look at who wrote the article. How can you “discover” a story that has already been shared many times by the people who were there?

At the end of the day, this story doesn’t belong to me, even though I connect to it on levels that not everyone will truly understand. This story belongs to the six boys, now all grown up with families of their own. Men who knew the comfort of each other’s laughter and singing for 15 months. Men who prayed, and prayed and prayed, till one day their prayers were answered. Tevita Siola’a, Sione Fataua, Luke Veikoso, Fatai Latu, Kolo Fekitoa and Sione Totau deserve to tell their stories, like I have, and damn, they all deserve to feel like they can own it, unapologetically.