Right-wing lobby group Hobson’s Pledge is leading the charge against customary marine title claims, but many still don’t know what that actually means.

In theory, New Zealanders have a right to access pretty much any beach in Aotearoa, except for some special wildlife areas where permission from DOC has to be given. Otherwise, you can basically land your boat or swim to any beach your heart desires. However, what you can’t do is walk freely across private land to get to any beach you like.

That second part is what’s fuelling the return of fear around customary marine titles – the belief that beaches will become inaccessible to everyday New Zealanders if titles are granted to local Māori.

The government recently announced some planned changes to the law, effectively to overturn a decision from the Court of Appeal that lowered the threshold for Māori customary marine title claims. The court ruled that iwi or hapū didn’t have to prove undisturbed use or occupation of the coastal area since 1840 to be eligible for customary marine title. The government responded by saying the courts had set the bar for claims lower than parliament intended, so they’re now drafting a bill to reset it higher. As 1News recently reported, the minister told seafood industry lobbyists changing the standard would reduce claims by around 95%.

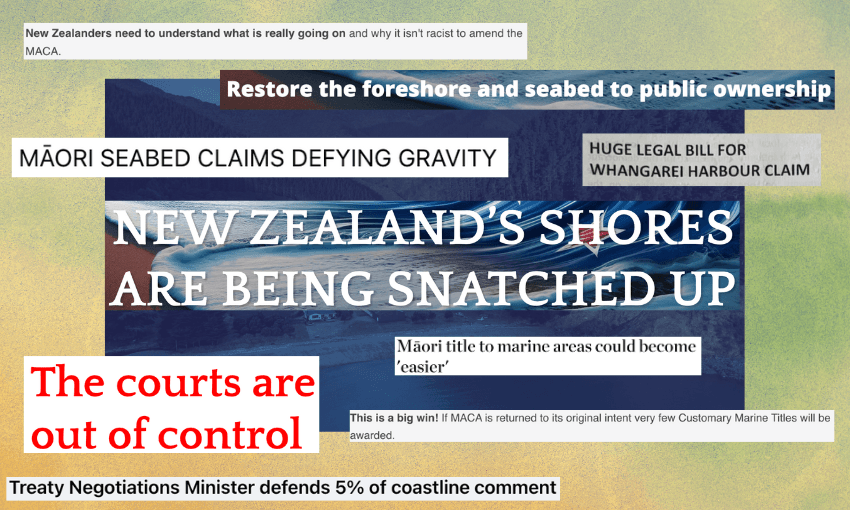

At the same time, right-wing lobby group Hobson’s Pledge, led by former National leader Don Brash, decided the time was right to boost its Save our Shores campaign. The group paid for a controversial front page ad in the NZ Herald, calling for the return of the foreshore and seabed to public ownership. The ad attracted a lot of criticism for many reasons, but especially because no one currently owns the country’s foreshore and seabed. A key part of the campaign plays on fears of access to beaches and the right to fish being taken away as a result of customary marine title applications being made by Māori.

But what will a customary marine title actually mean for New Zealanders?

History

Our country has a chequered past when it comes to the foreshore and seabed. Before the arrival of non-Māori, tangata whenua used the beach and sea for landing their waka, fishing, collecting shellfish and seaweed, and even had the odd seaside scrap.

When referring to the foreshore, we’re talking about the land between the high tide mark and the low tide mark. Basically, it’s the sand that gets wet when the tides come in and go out. The seabed means the land under the sea, extending out to 12 nautical miles, or just over 22 km from the low tide mark.

With the signing of te Tiriti in 1840, the British suddenly claimed they owned the beaches and the seabed, ignoring any claims to ownership Māori might’ve had. There have been a few legal challenges around the Crown’s claim to ownership of the foreshore and seabed over the years, but none more famous than a case brought forward in 1997 by Ngāti Apa, a group of Māori from near Nelson. It took six years for the Courts to decide the case but in 2003, the Court of Appeal found there was no clear legal right of ownership for the Crown and Māori could challenge this claim.

The Ngāti Apa decision led to widespread fear that Māori would suddenly own all of the country’s beaches. In 2004, former National Party leader Don Brash (who is now a spokesperson for Hobson’s Pledge) made his infamous Orewa speech, where he suggested the government was pandering to Māori and heavily criticised affirmative action as being “special privileges”. Two months later, the government announced it would be introducing a law to claim Crown ownership of the foreshore and seabed. A 20,000 strong hīkoi took place that May, opposing the proposed bill. Despite the public pushback, the controversial Foreshore and Seabed Act was passed in November 2005.

As a result of the new law, Tariana Turia left the Labour government and formed Te Paati Māori in May 2005. Following the 2008 election, the National party entered negotiations with Te Paati Māori about reviewing the Foreshore and Seabed Act. In 2011, the Foreshore and Seabed Act was replaced by the Marine and Coastal Area (Takutai Moana) Act 2011, which said no one owned the foreshore or seabed and once again gave Māori the right to attempt to claim customary title.

Customary marine title

Customary marine title is a legal recognition of the customary rights of Māori over specific areas of the marine and coastal area. It does not give full ownership but does give certain rights, like the ability to say no to resource consents and control over certain activities in the area. To qualify for customary marine title, the group has to show they have used the area in a cultural way since 1840. Customary marine titles do not affect public access, navigation, or fishing rights, but they do give the title holders influence over the management and use of the area.

Since 2011, over 200 applications have been made from different groups for customary marine title over the foreshore and seabed. These applications cover basically all of the coastline around the country, except for a stretch between Awatoto, just south of Napier, and Aramoana, about another 90 km south. While customary marine title isn’t the same as owning the beach or the seabed, there are some special rights it gives the holders.

Groups who have customary marine title can apply to have areas of a beach or ocean recognised as wāhi tapu. These are usually sites of cultural significance, like places where a fight has happened, someone has been buried, or an important item has been found. For example, on the Poutō Peninsula near Kaipara, there is an area where the remains of a rangatira are said to have been buried in the sand. The spot is now underwater, because of the shifting sands and tides. If given status as a wāhi tapu, a rāhui could be put in place over the area, stopping people from accessing it or fishing there. A warden could be employed to help carry out a rāhui and maintain the mana and tapu, or sacredness, of the space. That being said, no rāhui can stop a person from collecting their fishing quota from within a wider quota area.

Another power customary marine title gives the holders is the ability to approve or deny new applications for resource consent or conservation activities in the area. If someone wants to set-up a mussel farm, restore some sand dunes, or do something similar, they have to first talk to the customary marine title holder and get their blessing. Along with the restrictions around fishing, this right has seemed to spook the fishing industry, who have successfully convinced the government to legislate over the courts.

Customary marine title holders also get ownership of non-nationalised minerals, or basically any minerals in the sand or sea that aren’t oil, gold, silver, or uranium. This means they can sell the rights to mine the minerals, or even mine them themselves if they want to. Examples include things like copper, iron, lithium, cobalt, and even rare earth elements. Some of these minerals are worth money and groups like Hobson’s Pledge think all New Zealanders should have a right to profit from their extraction.

So does anyone actually own the beach?

Well, in some cases, yes. In 2003, Land Information New Zealand found that around 6,000km of land next to the country’s coastline was privately owned. Just under 4,000km, or 67% of that land was held in general title. The remaining 33%, or 2,000 km of land was held in Māori title. Another interesting thing to note is that there are just under 12,500 privately owned blocks of land that are within the foreshore area.

While private ownership doesn’t always mean the beach can’t be accessed by land, a large amount of the neighbouring coastline is inaccessible by foot. There are some obvious examples of where this is the case, like a port, but there are also lesser known cases of what are pretty much private beaches, like entire peninsulas gated off in the Bay of Islands or beaches on Waiheke island only accessible via private farms. More often than not, access to these beaches is blocked because the land around it is privately owned.

With the scab once again being ripped off foreshore and seabed issues in Aotearoa, tensions are starting to reach boiling point. While it’s unlikely the current minister of several relevant portfolios – Māori Crown relations: Te Arawhiti, Māori development, Whānau Ora, conservation – Tama Potaka will cross the floor like Tariana Turia did in 2005 over the issue, it will undoubtedly make for some awkward interactions between him and the Māori authorities he has to deal with on a daily basis.

We’ve already seen a number of nationwide protests in response to the current government’s actions, with more planned. There have been several urgent Waitangi Tribunal inquiries into the government’s policies, with another currently underway that began on Monday focusing on customary marine title. With the bill to amend the act currently being drafted and neither side willing to back down, it seems the foreshore and seabed issue will be around for a while longer.

This is Public Interest Journalism funded by NZ On Air.